Let Me Tell You about the Birds and the Bees: Swarm Theory and Military Decision-Making

30 Dec 2015

By Ben Zweibelson for Canadian Military Journal (CMJ)

This article was external page originally published in Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer 2015) of the external page Canadian Military Journal, a publication of the external page Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces.

“No single person knows everything that’s needed to deal with problems we face as a society, such as health care or climate change, but collectively we know far more than we’ve been able to tap so far.” -Thomas Malone (MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence)[i]

Introduction

Since the 1990s, Western military organizations have demonstrated periodic interest in whether the emergent behavior of decentralized systems, commonly referred to as ‘swarm theory’ or ‘swarm behavior,’ might be relevant in military applications. Defence innovators such as the RAND Corporation sponsored multiple studies on swarm theory in the past decade and a half, and recent popular books such as The Starfish and the Spider offer tantalizing prospects on decentralized organizations for future military applications.[ii] Clearly, the notion of alternative organizational intelligence and decentralized problem solving has sparked the interest of military academia. Is this another techno-centric fad, or does swarm theory offer military applications superior to traditional methodologies? Can the joint military community gain anything from considering swarming constructs?

Perhaps the deeper question is whether the ‘buzz’ of an exotic theory missed a larger point of reflecting upon the hierarchical and centralized organizational structure that define virtually all Western military organizations today. Can swarm theory, something that functions in the antithesis of centralized hierarchies, be of any use to our militaries? Is there anything beyond literal adaptations of swarm theory for robots and technological applications – can we convert General Officers into “Queen Bees” for certain complex situations, and would this do us any good? Can we make military decisions in any process other than the hierarchical, centralized, and dominant form that permeates our doctrine, education, and practice? [iii] Lastly, can we gain perspective with respect to how our military hierarchy drives organizational decision-making to create environments that are rigidly inhospitable to introducing swarm constructs?

This is not an article about how to tactically employ swarm theory as a form of maneuver, or a simplistic trick on getting squads to attack an objective while making decentralized decisions in a swarm-like manner. ‘Slamming’ two dissimilar ideas in linear and simplistic construction represents a hazardous and largely uncreative way to go about innovation.[iv] Instead, we need to address the overarching topic of how the military makes sense of different environments, and subsequently makes decisions that lead to actions. While tactical leaders might find these concepts interesting, strategic planners, inter-agency and joint operators, as well as governmental and contractor organizations that work closely with the military, may gain some insight with respect to how swarm theory and modern military organizations function.

First, let us define what swarm behavior is as a construct for organizational decision-making and emergent behavior, so we might frame the potential paradoxes and tensions between decentralized decision-making and how we, as a military profession, tend to approach most every decision in a conflict environment.[v] Potentially, swarm applications offer some revolutionary innovations on the horizon, which tend to draw military interest initially – although largely the interest has remained decidedly technological and tactical in a literal sense. This article offers some immediate opportunities in both a pedagogic (thinking about how we teach) sense, and through an epistemological (thinking about how we know what we know) reflection upon military decision-making as a profession of arms.[vi] Thus, joint and combined military operations in a wide variety of applications are applicable here, whether discussing air, land, or maritime operations. To incorporate any swarm constructs into how we make decisions as a military force, we may need to alter, albeit temporarily, some deeply held institutionalisms.

Swarm Theory: Decentralization and Local Conditions

Why does research about the organizational structure of bees, ants, and other non-military organisms matter for serious military debate? ‘Swarm Theory’ overlaps into many disciplines, to include evolutionary biology, mathematics, and computer modeling, as well as numerous sociological adaptations over the past several decades.[vii] Often, it happens around us without us even realizing it. The next time you are driving in highway traffic at night and you notice a pattern of red brake lights from cars well ahead of you, observe how waves of traffic respond without anyone directing us to brake. The next time you enter a crowded elevator, notice how people shift and maintain fairly even distance while decreasing space to let more people in, without anyone saying a word. These are simple examples for what in nature we see organisms that are often simplistic, such as ants or bees, and yet collectively, there is something far greater occurring that promotes complex problem solving at the organizational level. Essentially, emergent behavior and complex system adaptation occurs through a ‘swarm intelligence’ despite the organization being comprised of many often simplistic individuals that respond only to local conditions in a highly decentralized span of control. To understand the ‘strangeness’ of swarm, we also need to look inward at how traditional military organizations work to illustrate the contrasts. These are things we often take for granted.

Unlike a traditional military hierarchy where the general gives orders, and at the base of the organizational pyramid, many units follow these orders, in swarm structures like an ant colony or beehive, the queen bee issues no orders at all. The worker bees follow no directives from higher, and merely respond to local conditions and the immediately surrounding bees. The queen has no idea what the rest of the colony is doing, and focuses only upon her own local tasks. Collectively, the entire colony generates collective intelligence that demonstrates ‘synergy’ in that the whole is greater than the mere sum of the parts. Local decisions drive impressive organizational responses. For instance, an ant may switch from scouting for a food source to retrieving food from a discovered source once a certain type and number of other ant pheromone trails are established in the ant’s local environment. No ant leadership directed him. Instead, local conditions coupled with various instinctive triggers govern the actions of many simplistic organisms.

Deceptively simple, swarm intelligence provides an ant colony some amazing abilities to confront many complex and emergent problems in an entirely non-hierarchical way. This is in strong contrast to the linear, sequential, and hierarchical approach employed by most governmental, business, and military organizations where extensive ‘top-down’ planning and managing drives collective actions. Both constructs tackle complex environments, both adapt and respond to emergence in the environment, and both make sense of their environments in order to subsequently transform them. Yet, a military force and an ant colony do things remarkably differently. While ants are unable to change from swarm organization to anything else, we as humans have the luxury of considering whether our preferred centralized and hierarchical process is most effective, or whether we might adapt some lessons from our swarming friends.

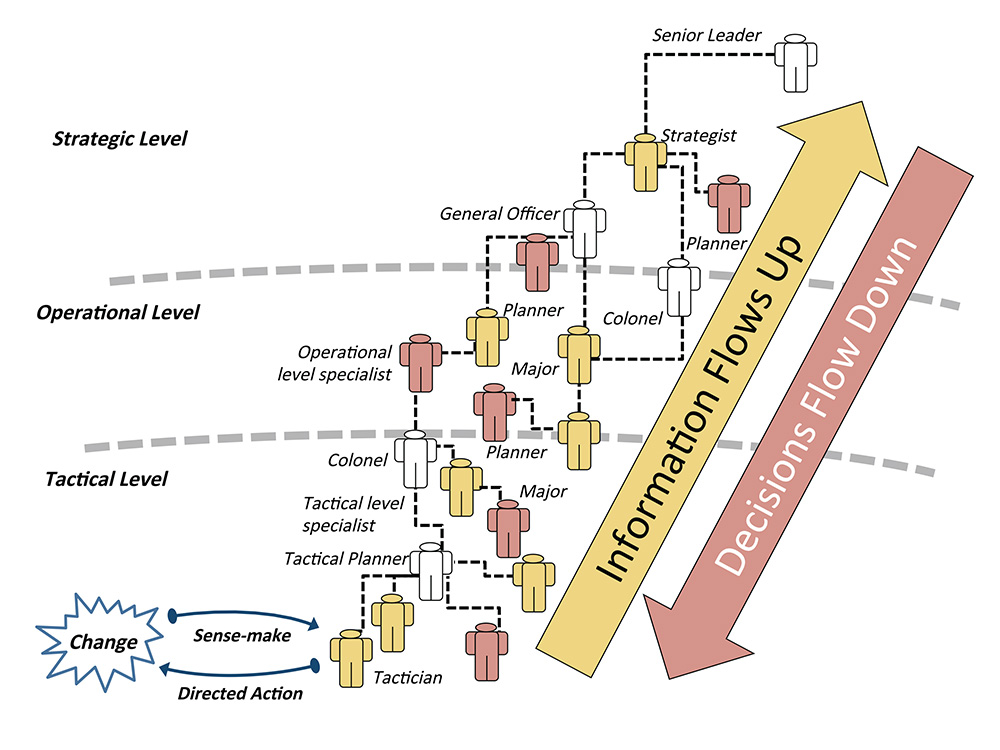

This distinction in structure between centralized hierarchical and decentralized swarm-thinking organizations transcends the methodologies of the institution; essentially the rules and principles for accomplishing tasks and making sense of an environment. Ultimately, this distinction addresses at the epistemological level (how we know to do something) how an institution knows to organize, decide, act, adapt, and learn. [viii] Figure 1 illustrates the traditional military hierarchy of command and control, where information flows up and decisions flow back down. Formal decision-making models, such as the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP) and the Joint Operational Planning Process (JOPP), rely upon these rigid hierarchical structures for directing information, conducting analysis, focusing staff functions, and directing subordinate activities towards the organizational objectives. Other governmental agencies and associated contractors follow similar structures with subtly different language, concepts, and identities. Military professionals likely know only this one methodology with respect to how to plan and organize actions. We also take this for granted.[ix]

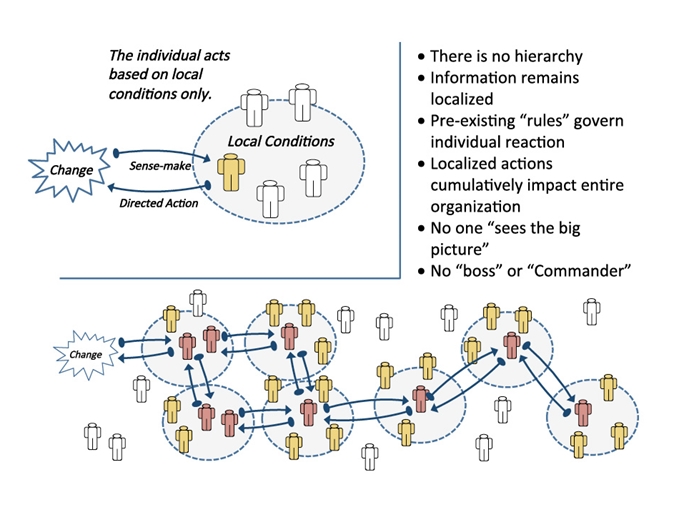

What is extraordinarily different from centralized organizations, such as the military institution, is how swarm intelligence functions. While a hierarchical organization might develop complex campaign plans and extensive planning and analysis to determine the most effective supply routes in an assigned area, an ant colony solves this complex problem using decentralized organizational approaches with absolutely no directives or hierarchical decision-making. Yet, through localized conditions, chemical sensors for communication, and individual decision-making, an ant colony rapidly establishes the shortest routes for frequently changing food sources, and readily adapts to changes to the environment. Birds, bees, and other animals in nature offer variations of swarm intelligence, although swarm theory expands beyond nature into other constructs. An ant might detect a chemical trail that says: “Hey, there is food down this path,” but if that ant senses that there are more than four ants nearby that are already heading to the food source, that ant may automatically switch to “…return to the colony and assist with food storage” instead. No ‘ant leader’ is on the ground directing them- the ants switch behaviors and adjust chemical trails to communicate locally with nearby ants only. For military personnel that have conducted individual land navigation training, similar patterns emerge around land navigation points that they are trying to find. Without anyone communicating, groups of navigators tend to vector in collectively on the same point and adjust their navigation, based upon proximity to other students moving in a similar direction. At difficult locations, students swarm while playing off other students’ successes or frustrations until one student finds the illusive point, and then only those close enough to locally observe him will follow suit without anyone being in charge or providing direction. Swarm works with simplicity at the local level, yet remains capable of solving complex and adaptive problems at the organizational level without centralized decision-making.

Modern network and internet companies, as well as NASA, are investigating and building swarm-smart approaches to real-world human problems where traditional approaches are currently insufficient or inefficient.[x] Figure 2 offers an illustration of how decentralized swarm organization differs from the traditional military hierarchy.

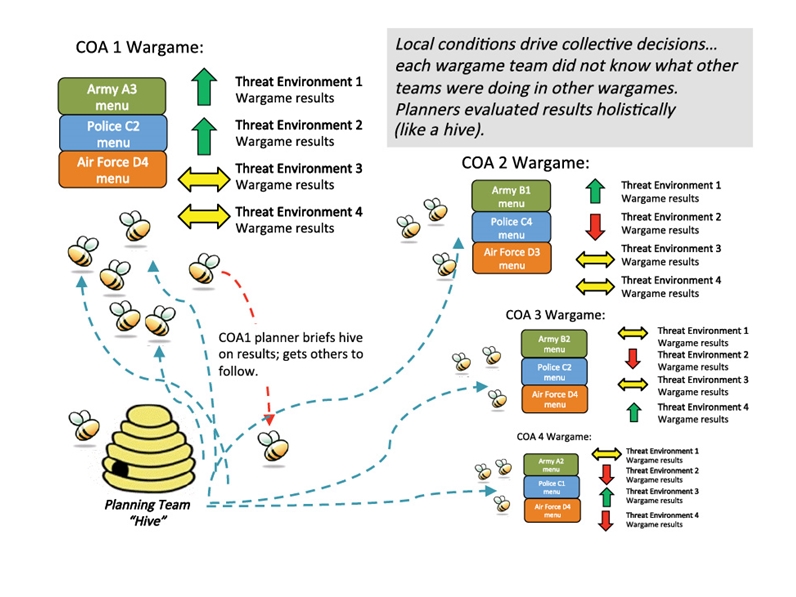

Conceptually, the differences between centralized and decentralized organizations confronting decision-making are significant. I do not suggest we abandon the traditional military hierarchy and begin imitating an ant colony, as deliberate metaphoric applications only confuse and misinterpret what swarm potentially offers. However, some aspects of military decision-making could improve with the integration or substitution of swarm’s decentralized constructs for ‘wicked’ problems in complex military environments. In 2012, as a lead planner for a complex NATO problem on how to conceptually reduce the Afghan National Security Forces from 352,000 soldiers, police, and airmen to an unknown post-2015 size, I inserted a swarm construct into the traditional military ‘war-gaming’ methodology for decision-making.[xi] Our conceptual work was specifically for policy makers in Washington. However, the unclassified results would subsequently drive follow-on planning by numerous incarnations of various plans and branch plans at the national level for military forces in Afghanistan and continue to this day. [xii] Drawing from observations on how a bee colony selects new colony locations through scouts that never examine other sites besides the one they examined, I constructed the NATO planning team’s war game sessions around similar decentralized constructs. [xiii] Each of the five ‘mini-teams’ only war-gamed their particular security force option, all the courses of action had a combination of positive and negative traits, and the local conditions of the ‘mini-team’ and their war-game became relevant for group discussion. Figure 3 uses an illustration from the unclassified results of that project.[xiv]

As our groups collaborated in a non-traditional war-gaming approach to discuss each mini-team’s localized findings, the overall group began like bees in the hive to drive two of the five courses of action to the top. Largely devoid of traditional hierarchical processes, and lacking the ‘run through every course of action as a group’ turn-based methodology in standard military war-gaming, our ‘swarm construct’ in military decision-making demonstrated success as the results were accepted by NATO nations and implemented in 2012 by ISAF for subsequent security force development. [xv]

In this example, we did not use robots equipped with ‘swarm programming,’ or run the courses of action through software that eliminates our hierarchical methodology. Instead, by addressing our epistemological framing of how we make decisions as a military profession, we consciously selected a swarm-centric construct as a substitution to traditional turn-based war game approaches. There are myriad applications for swarm where military planning teams might infuse decentralization and local-conditions with collective collaboration, but I would like to highlight a few key tensions that emerge in practice when attempting to insert swarm applications into military problem solving.

Turning Soliders into Bees: Gaining Decentralization in Decision-Making

There are several organizational hurdles that exist for any professional seeking to integrate swarm constructs into the traditional military decision-making approach. First, the dominance of the military hierarchy absolutely governs the flow of information up and decisions down. In any swarm application, this centralized decision-making construct must be tempered in a measurable way. While it is problematic for any organization to view a boss as anything but the boss, a planning team composed of a variety of professionals should be able to operate democratically with the senior decision-maker absent from the swarm application.[xvi] Planners must set aside the centralized military hierarchy, even if just within the confines of a small planning team’s work area, to allow the epistemologically different construct of swarm theory to function.

Second, in order for local conditions to support a swarm construct, all the planning teams must agree upon fundamental ‘instincts’ or ‘triggers’ for action – this enables a planner to support swarm intelligence by acting only upon local conditions and in ignorance of the ‘bigger picture.’ For war-gaming multiple courses of action, each ‘pod’ of planners need not know what other planning pods are doing with other war-gaming efforts, provided that all the pods are prepared to make localized decisions, based upon a shared collective decision-making construct. Establishing decision support criteria, using a specific and agreed-upon language, and using the same quantifiable information across all the war games provided our planning pods the proper ‘instinct’ structures for group decisions. We all must agree what a positive or negative decision criterion means in general, to allow localized and context-specific decisions to occur in a decentralized swarm approach.

Third, the plural democracy of a decentralized organization must operate uninhibited by the traditional military hierarchy in order to accomplish best results in planning for the period where swarm disrupts the traditional hierarchy. When multiple planning pods collaborate to discuss findings and make recommendations, one must downplay a single senior leader or influential member from dismantling the decentralized process. In the NATO project, our planning group assembled, and metaphorically, each mini-team presented a ‘bee dance’ to brief where they considered their course of action should fall. Over time, those teams that provided effective arguments swayed more planners to their position, and collectively, the entire ‘hive’ eventually settled upon one course of action out of an original five. One negative aspect to consider is simply human nature. Humans are not simplistic organisms, and dominant personalities might easily upset a swarm approach by reinserting the military hierarchy in order to achieve other agenda s- even subconsciously. The group has to recognize and prevent this iteratively in reflective practice.[xvii]

Fourth, military planners might reject swarm theory outright, or unconsciously resist it if expressly told so prior to the planning effort. If a planning team is not familiar with swarm theory, or the lead planner anticipates that a swarm construct might better function without the participants implicitly aware, one might couch the decision-making modification without using the term ‘swarm theory,’ or even revealing the deviation. I applied this in the NATO project due to limited time constraints and the wide range of actors in our group. However, by using familiar military terms and maintaining traditional products, such as the decision support matrix, the planning pods remained unaware and still functioned in a swarm approach to deliver a selected course of action. By framing the war-game in familiar terminology and aspects of doctrinally accepted planning concepts, our planning team readily entered into a swarm-like approach without any resistance. This does have an element of deception to it. However, due to limited time and other constraints, we were not prepared to give the team a crash course in swarm theory and other design considerations. With the framework in place, the teams shifted into a decentralized and local-conditions manner of problem solving, and later, they were able to shift back into traditional decision-making without issue.

This leads to the next concern, where one could argue that the traditional military hierarchy is not only unwilling to knowingly tinker with the preferred method of centralized decision-making, it will openly attack any decentralized applications as being ‘not doctrinally sound,’ deviant, or incompatible. Part of this stems from a normal defensive posture against disrupting how our organization functions, but it also stems from some vulnerability within the overall strength of centralized management. Our strength in following orders becomes a weakness in adapting new and useful approaches to solving problems that resist our centralized efforts.

Buzz Words and Gimmicks: Swarms Eat Hierarchies; Hierarchies Eat Swarms

Our profession tends to stick to one epistemological construct where we know how we problem-solve because we follow our doctrine and use a shared lexicon of terms and principles.external page [xviii] The traditional military hierarchical approach favors a highly reductionist and sequential process where we attempt to break complex situations down into neat piles of facts, labels, and categories. When Napoleon (and later the Prussians) began using specialized staff elements, out of this, the modern military staff gradually emerged where the major components of military operations are categorized into special staff functions, such as administration, intelligence, maneuver, logistics, communication, and so forth. The Napoleonic Staff process itself is a self-reinforcing element where the military intelligence officer handles enemy information; the engineer addresses his specialized field, and so on.[xix] While our traditional decision-making methodology remains a highly flexible and responsive process to push information ‘up the chain’ and to drive decisions down, a major weakness in this approach is a decidedly rigid outlook towards anything that changes this process, as well as the tendencies toward categorization, reductionism, and linear causality.[xx] Swarm theory functions from an entirely dissimilar epistemological construct where decentralization reigns and things like reductionism are irrelevant. This ‘makes for strange bedfellows,’ and produces significant organizational barriers for any leader interested in applying swarm theory in our decision-making construct. external page [xxi]

Often, injecting something like swarm into any established military practice quickly results in either the group sprinkling a misused term into traditional practice with a ‘buzz word’ fervor, or the profession outright rejects the attempt, due to the significant epistemological differences highlighted. For swarm theory’s decentralization element, this means that the highly familiar “I say…you do” relationship between superiors and subordinates is suspended. Obviously, if poorly implemented, this will cause more harm than good. For swarm’s localized emergence element where a pod of planners do not know what the rest of the organization is doing, this means that ‘situational awareness’ and our normal gorging of over-information is also suspended. More significantly, for branch and service self-identity concerns, swarm’s localized emergence element largely rejects the categorization effect of the Napoleonic staff specialization. Planners are free to respond to conditions based upon the local environment, and not based upon specialization where the engineer “…has no business thinking about enemy capabilities because that is the Military Intelligence Officer’s lane.” For these numerous epistemological tensions, leaders cannot apply swarm theory ‘willy-nilly’ into any military decision-making just in the hopes of sparking a creative solution to a troubling problem. A senior leader does not saunter up to the group with, “…today, we are going to think like bees to finally figure out how to defeat an insurgency within a war-torn, economically stagnant, and ideologically dissimilar region.” Instead, any swarm application requires focused framing of the planning team, as well as ‘ground rules’ with precautions taken to mitigate the aforementioned obstacles associated with how our institution protects the hierarchical and centralized construct.

Conclusions: Float like a Butterfly, Think like a Bee (from Time to Time)

Revolutions in technology and information are changing how we make sense of military conflict environments. Some of our traditional approaches with respect to problem solving were more effective yesterday than today – but our institutions tend to retain some habits far longer than necessary. [xxii] Nothing defines the military profession greater than our centralized decision-making process grounded in a hierarchy of rank, experience, status, and position. While I do not suggest that we should abandon the very constructs that make a military force a disciplined, self-sufficient, and flexible organization, there are benefits in looking to contrary organizing constructs for inspiration in complex problem solving. Generals should not become ‘queen bees,’ but a military staff might make sense of a particularly ‘wicked’ problem from a fresh perspective by taking a page from swarm theory. novel solutions, and we cannot assume a myopic stance that every single military problem will ultimately be ‘solvable’ by applying our preferred centralized hierarchy approach. If that were true, why would nature even entertain organisms using swarm at all? Plenty of other insects do not use it at all, and flourish alongside ant colonies and beehives. Unlike insects or other organisms, we can choose to modify how we make decisions – unless we are unwilling to do so.

As technology ushers in new concepts such as ‘meta-data’ collection, ‘flash mobbing,’ social knowledge construction (Wikipedia), cyber terrorism, and other human-driven endeavors that further complicate how the military ‘sense-makes’ in complex conflict environments, our traditional problem-solving methodology may prove inadequate, or possibly incomplete.[xxiii] Mission analysis, MDMP, or war-gaming may retain the sequential and reductionist procedures for general application. However, an adaptive planning team may chose at times to restructure aspects of any of these constructs to include swarm theory. As offered in The Starfish and the Spider, hybrid organizations that blend centralized and decentralized aspects into a flexible organizational construct offer a better chance of adapting to future rivals.[xxiv] For military decision-making, this may include swarm components. Select applications, used judiciously and with reflective practice, may generate solutions for solving the right problem within an elusive and dynamic military context, rather than a continuous cycle of solving the wrong problems and creating new ones.[xxv] A general or senior leader need not become a ‘Queen Bee’ and surrender the centralized authority of decision-making. However, planning teams comprised of many inter-agency and diverse partners might adapt ‘swarm-like’ constructs for sense-making and decision-making in carefully constructed planning environments. Under these conditions, even a ‘wicked’ problem might become less confusing and uncertain through a blending of decentralized and local-conditions centric thinking.

[i] Peter Miller, “The Genius of Swarms,” in National Geographic Magazine (July 2007). Retrieved on 6 December 2013 at: external page http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/print/2007/07/swarms/miller-text . Miller quotes Thomas Malone from MIT’s Center from Collective Intelligence.

[ii] John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, “Swarming and the Future of Conflict,” RAND National Defense Research Institute (Santa Monica, CA:, 2005). See also: Sean Edwards, “Swarming on the Battlefield: Past, Present, and Future,” RAND National Defense Research Institute (Santa Monica, CA: 2000). See also: Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom, The Starfish and the Spider (New York, NY: The Penguin Group, 2006).

[iii] Natalie Ferry and Jovita Ross-Gordon, “An Inquiry into Schön’s Epistemology of Practice: Exploring Links Between Experience and Reflective Practice,” in Adult Education Quarterly, Vol. 48, Issue 2, (1998), p. 99.

[iv] Karl Weick, “The Role of Imagination in the Organizing of Knowledge,” in European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 15, (2006), pp. 447-448.

[v] Karl Weick, “Rethinking Organizational Design,” in Managing as Designing, Richard Boland Jr. and Fred Callopy (Eds.), (CA: Stanford Business Books, 2004), p. 47. See also: Valerie Ahl and T.F.H. Allen, Hierarchy Theory: A Vision, Vocabulary, and Epistemology (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1996), p. 1.

[vi] Donald A. Schön, “The Crisis of Professional Knowledge and the Pursuit of an Epistemology of Practice,” in Teaching and the Case Method, Instruction Guide, Louis Barnes, C. Roland Christensen, and Abby J. Hansen (Eds.), (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1987), pp. 241-254.

[vii] Arquilla and Ronfeldt, pp. 25-27. See also: Michael Hinchey, Roy Sterritt, and Chris Rouff, “Swarms and Swarm Intelligence,”in Software Technologies (April 2007). Retrieved on 20 December 2013 at: external page http://eprints.ulster.ac.uk/20692/1/04160239-2007-Swarms_and_Swarm_Intelligence.pdf. See also: Peter Miller, “The Genius of Swarms.” See also: Rob White, “Swarming and the Social Dynamics of Group Violence,” in Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (Australian Institute of Criminology, October 2006, No. 326).

[viii] Mary Jo Hatch and Dvora Yanow, “Methodology by Metaphor: Ways of Seeing in Painting and Research,” in Organizational Studies, Vol. 29, Issue 1, 2008), p. 30. Hatch and Yanow provide epistemological frameworks using painting metaphors to illustrate dissimilar organizational sense-making of environments.

[ix] Karl Weick, “Rethinking Organizational Design,” p. 42. Weick discusses how highly coordinated groups are “…the last groups to discover that their labels entrap them in outdated practices.”

[x] Hinchey, Sterritt, and Rouff, pp. 112-113.

[xi] Ben Zweibelson, “Does Design Help or Hurt Military Planning: How NTM-A Designed a Plausible Afghan Security Force in an Uncertain Future- Part II,” in Small Wars Journal, 16 July 2012. Retrieved on 20 December 2013 at: external page http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/does-design-help-or-hurt-military-planning-how-ntm-a-designed-a-plausible-afghan-security-0.

[xii] Personal correspondence with fellow planners as of December 2013 while I was deployed to Afghanistan. Several planners contacted me personally on our group’s prior work because they were the planning team working the latest version of what the ANSF would look like in 2015-2016.

[xiii] Miller.

[xiv] Zweibelson, p. 5. This article re-uses Figure 13 as Figure 3 in this article.

[xv] Thom Shanker and Alissa Rubin, “Afghan Force Will Be Cut after Taking Lead Role,” in The New York Times, 10 April 2012. Retrieved on 20 December 2013 at: external page http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/11/world/asia/afghan-force-will-be-cut-as-nato-ends-mission-in-2014.html?_r=0. “The defense minister, General Abdul Rahim Wardak, noted that the projected reductions beyond 2014 were the result of “…a conceptual model for planning purposes” of an army, police, and border-protection force sufficient to defend Afghanistan.” Wardak references the official results of the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan (NTM-A) reduction plan where we proposed a 230,000- size force. In my previous deployment to Afghanistan under NTM-A, one of my primary duties was to accompany the NTM-A Commander to all engagement with Minister Wardak, to serve as the “Afghan Army Portfolio Manager,” and to interface with the Department of State and Washington civilian policy makers.

[xvi] John Molineux and Tim Haslett, “The Use of Soft Systems Methodology to Enhance Group Creativity,” in Systemic Practice and Action Research (December 2007, Volume 20, Issue 6), pp. 477-496. Molineux and Haslett cite numerous studies on creativity and group dynamics to argue that democratic (plural, not hierarchical) and collaborative leadership fosters increased creativity.

[xvii] Karl E. Weick, “Improvisation as a Mindset for Organizational Analysis” Organizational Science (Volume 9, No. 5, September-October 1998), p. 551.Organizations follow “…the chronic temptation to fall back on well-rehearsed fragments to cope with current problems even though these problems don’t exactly match those present at the time of the earlier rehearsal.”

[xviii] Gareth Morgan, “Exploring Plato’s Cave: Organizations as Psychic Prisons,” in Images of Organization, SAGE Publications, 2006, p. 229. “Thus, the bureaucratic approach to organization emphasizes the virtue of breaking activities and functions into clearly defined component parts…we manage our world by simplifying it.”

[xix] Ian Mitroff, “Systemic Problem Solving,” in Leadership: Where Else Can we Go? Morgan McCall, Jr. and Michael Lombardo [Eds.],(Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1978), pp.133-134. Mitroff discusses what he terms “Type III leadership errors” as related to a reductionist problem-solving approach.

[xx] Morgan, p. 229. “Many of our most basic conceptions of organization hinge on the idea of making the complex simple…we manage our world by simplifying it.” See also: Alex Ryan, “The Foundation for An Adaptive Approach,” in Australian Army Journal , Vol. 6, Issue 3, 2009, p. 70. “With the industrial revolution, the planning and decision-making process gradually built up a well-oiled machine to reduce reliance on individual genius.” See also: Valerie Ahl and T.F.H. Allen, Hierarchy Theory: A Vision, Vocabulary, and Epistemology (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), p. 1. “Contemporary society has ambitions of solving complex problems through technical understanding…the first strategy is to reduce complex problems by gaining tight control over behavior. It is a mechanical solution in the style of differential equations and Newtonian calculus.”

[xxi] Henry Mitzberg, Duru Raisinghani, and Andre Theoret, “The Structure of ‘Unstructured’ Decision Processes,” in Administrative Science Quarterly (Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University, June 1976, Vol. 1), p.142. The authors distinguish the concept of ‘search routine’ in problem solving as “a hierarchical, stepwise process “…[that] begins in local or immediately accessible areas, with familiar sources.”

[xxii] Morgan, p. 237. “A particular aspect of organizational structure…may come to assume special significance and be preserved and retained even in the face of great pressure to change.”

[xxiii] On ‘flash mobs, ‘ see: Anne Duran, “Flash Mobs: Social Influence in the 21st Century,” in Social Influence (2006, Vol. 1, Issue 4), pp. 301-315. See also: Hannah Steinblatt, “E-Incitement: A Framework for Regulating the Incitement of Criminal Flash Mobs,” Forham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L. J. (May 2013, Vol. 22), pp. 753-793.

[xxiv] Brafman and Beckstrom. The authors entertain hybrid organizations that use both centralized and decentralized elements in their final chapter.

[xxv] Mitroff, pp.130-131. See also: Henry Mintzberg and Frances Westley, “Decision Making: It’s Not What You Think,” in MIT Sloan Management Review (Spring 2001), p. 91. The authors observe that in the “thinking first” workshop, participants relied on science, planning, and other aspects shared by MDMP where “almost no time is spent in discussing how to go about analyzing the problem.” See also: Natalie Ferry and Jovita Ross-Gordon, “An Inquiry into Schon’s Epistemology of Practice: Exploring Links between Experience and Reflective Practice,” in Adult Education Quarterly (Winter 1998, Vol. 48, Issue 2), p. 8.