Back to the Future: Economic Retrenchment in Russia

8 Apr 2016

By Peter Rutland for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article recently appeared in Russian Analytical Digest No. 180, which is a series published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS).

Abstract:

This article provides an overview of the economic situation in Russia at the beginning of 2016. While Russia is experiencing negative growth and faces numerous international difficulties, the problems are not likely to lead to political change in the country.

A Shrinking Economy

As 2015 drew to a close, Vladimir Putin seemed to be riding high. His assertive foreign policy led to a surge in popular support at home and new attention from other leading powers. The Russian-backed insurgency in Ukraine plunged that country into chaos, casting doubt over plans for closer integration with European institutions. Putin’s dispatch of the Russian military to Syria in September won Russia a seat at the table in New York on 18 December where the international community tried to come up with a common strategy to end the civil war and defeat ISIS.

However, these achievements may well be short-lived. It is not clear that the Russian military, while much improved, has the capacity to escalate its intervention in Ukraine and Syria should that be needed. Russia remains a lonely player on the international stage. Its closest allies—Belarus and Kazakhstan—were alarmed by the annexation of Crimea; while China’s “One belt, one road” project is carving a swathe through Russia’s traditional sphere of influence in Central Asia.

The main cloud on Russia’s horizon, however, is the economy. Putin issued a stark warning to the Federal Assembly on 3 December 2015: “We must be ready that the period of low commodity prices and, possibly, external sanctions may stretch out for an extended period. If we change nothing, we will just eat through our reserves as economic growth hovers near the zero mark.”[1]

This situation is strangely reminiscent of the trajectory of the former Soviet Union, which was able to challenge the United States in military power, but unable to provide Russian consumers with the food and consumer goods they wanted.

Economics and Nationalism in Tension

For the most part, Putin has pursued neoliberal economic policies at home while at the same time burnishing his image as a strong nationalist who had restored Russia’s prestige in the world. The Ukraine crisis of 2014 would push this awkward balancing act to breaking point.

After ascending to the presidency in 2000, Putin did not dismantle Boris Yeltsin’s market reforms, since he understood that Russia would only survive and prosper if it embraced capitalism and integrated with the global economy. He took steps to prevent the oligarchs from interfering in the exercise of political power, and restored tighter state control over strategic sectors such as energy and military industry. But otherwise, the capitalist elite were encouraged to enrich themselves. On Putin’s watch, the number of billionaires swelled from a dozen to a hundred.[2] Capital controls were lifted, the bulk of Russia’s foreign debts were repaid, and the ruble became a fully convertible currency.

However, Russian nationalists such as Sergei Glaz'ev complain that international economic integration is eroding the political institutions and cultural norms that are central to Russian identity. Western affluence is corrupting the Russian elite and undermining its commitment to the country’s development. Glaz'ev wants to erect barriers to Western economic influence, to invest the petrodollars in Russian manufacturing and infrastructure, and to create an alternate Eurasian trading bloc.

Cognizant of the challenge from the nationalist right, Putin has tried to break out of the U.S.-led global economic order by promoting alternative institutions, such as the BRICS alliance of emerging economies, and an economic union in post-Soviet Eurasia.

The BRICS Project

The term “BRICs” was coined by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill in 2001 to describe the rising economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China (joined later by South Africa). In the 2000s the BRICS experienced rapid growth, riding the wave of deep globalization. Russian leaders enthusiastically seized on the notion that these countries, with a rapidly rising share of the global economy (30% by 2014, in PPP terms), would be able to counter U.S. hegemony and draw up new rules of the global economic game. A series of annual diplomatic summits were instituted, starting with one in Yekaterinburg, Russia in 2009. Unlike Russia, the other members of the group were less interested in picking a fight with the U.S., but did see areas of common interest. The other four BRICS abstained in the 27 March 2014 U.N, General Assembly resolution which condemned Russia’s actions in Crimea. At that time Russia was expelled from the G8 group of industrial countries, which made its membership of the BRICS even more valuable.

Skeptics suggest that the disparate interests of the BRICS members (energy exporters vs. importers, democracies vs. autocracies) make it hard for them to come up with a common agenda. Advocates for BRICS argue that it can help the international community coordinate to promote stimulus packages (e.g. at the G20 summit in Pittsburgh in 2009) and avoid competitive devaluations.[3] Aleksei Mozhin, the Russian representative to the IMF, reports that since the 2009 G20 meeting the BRICS have engaged in “very intense” cooperation, caucusing in advance of IMF board meetings to develop common positions.[4] One of the main complaints is that the BRICS lack influence in institutions such as the IMF— where they held 11.5% of the voting quota. In 2010 they persuaded the U.S. to increase their share—but the U.S. Congress refused to ratify the changes, relenting only in December 2015.

The sixth BRICS summit in Fortaleza, Brazil in July 2014 agreed to create a New Development Bank (NDB—headquartered in Shanghai) and a Contingent Reserves Arrangement (CRA) for use in the event of financial crises—each with authorized capital of $100 billion.[5] In October 2014 China launched its own Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), with $100 billion capital. The U.S. boycotted the bank, but other developed economies were among the 57 nations that eagerly signed up. Together these new institutions will have greater lending capacity than the World Bank—and with fewer financial conditions attached. On the other hand, they may have strings of their own, such as mandating imports of equipment and even workers from China. China holds 26% of the votes in the AIIB, and most of its projects will likely serve Chinese interests—to secure the supply of resources in distant countries and to build infrastructure for their transport to China. These initiatives suggest that the BRICS have some real potential beyond just summit declarations. However, given Russia’s ostensible goal of diversifying away from resource exports, it is not clear how much Russia stands to benefit economically from these BRICS initiatives.

At the BRICS summit in Ufa, Bashkortostan in July 2015 Russia persuaded the others to sign a resolution condemning “unilateral military interventions and economic sanctions,”[6] but in practice, China seems more interested in promoting the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as a vehicle for economic partnership. There are several clouds on the BRICS horizon. With slowing growth in China, that country is importing less as growth shifts towards domestic consumption. This will be good for China but bad for the global economy, including Brazil and Russia, whose exports increasingly depend on the Chinese market. More broadly, there is a sense that the deep globalization of the 2000s (from which all the BRICS benefited) has been replaced by a period of retrenchment and regionalization—a world in which the globe-spanning BRICS make less sense. The BRICS countries have increasingly resorting to protectionist measures—including barriers against fellow-BRICS members.[7]

Regional Integration in the Post-Soviet Space

The European Union is Russia’s largest trading partner, but Russia’s exports consist overwhelmingly of commodities—oil, gas, metals and chemicals. Putin wanted to boost the prospects for Russian manufacturing by promoting free trade amongst the post-soviet countries. A regional trading bloc under Russia’s control would also have some strategic advantages, serving as an alternative to the European Union and affording a degree of insulation from the global economic institutions dominated by the U.S.[8] Putin redoubled these integration efforts in the wake of the 2008 financial crash, which saw sluggish growth in Europe.

Putin cajoled Belarus and Kazakhstan into joining the Eurasian Customs Union that was launched in 2010, which expanded into the Common Economic Space in 2012, and became the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) in 2015. By 2014 Russia only accounted for 10% of Kazakhstan’s trade, so President Nursultan Nazarbaev’s motivation was largely political: to remain on good terms with Moscow. Belarus in contrast remains heavily dependent on Moscow: Russia still accounts for 45% of Belarus’ trade. In 2014 Kyrgyzstan and Armenia were arm-twisted into joining the EEU, but the organization’s viability hinges on Kyiv’s participation. Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan add just 15% to Russia’s GDP (and 20% to its population). Ukraine would contribute another 10% to GDP and 30% to population.

This helps explain Putin’s willingness to do everything in his power to prevent Ukraine from signing an Association Agreement with the EU in 2013—which would have prevented that country from joining the Russia-led EEU.

The Ukraine Crisis

The ostensibly pro-Russia President Viktor Yanukovych, who came to power in 2010, dragged his feet over committing to the EEU, and instead negotiated an Association Agreement with the European Union. Russia insisted that the harmonization of standards and zero tariffs that the EU agreement entailed were incompatible with Ukraine’s membership in its own customs union. It is not clear whether Yanukovich ever seriously intended to sign the EU agreement, or was just using it as leverage to extract more financial concessions from Russia. Either way, at the eleventh hour, Yanukovich walked away from the deal with Brussels at the November 2013 Vilnius summit. Politics also played a role: the Ukrainian parliament refused to go along with Brussels’ insistence that former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko be released from prison. Moscow was jubilant: on 17 December 2013, Russia rewarded Yanukovych with a $15 billion loan and a cut in the price of natural gas from $400 to $268 per 1,000 cubic meters.

However, Yanukovych’s decision to abandon the EU deal triggered street protests which culminated in the Euromaidan revolution in February 2014 and Yanukovych’s flight from office. Putin retaliated by annexing Crimea and supporting separatists in Eastern Ukraine, triggering fighting that would kill over 9,000 people over the next two years. Russia suspended its loan, having disbursed just one $3 billion tranche, and Russia–Ukraine trade fell precipitously. The U.S., EU and several other countries imposed sanctions on Russian individuals and organizations involved in the annexation of Crimea. Ukraine’s new transitional government went ahead and signed the EU agreement on 27 June 2014, though they postponed implementation of the free trade agreement for a year, until January 2016. Russia immediately imposed higher tariffs on Ukrainian imports: Kazakhstan and Belarus declined to follow suit.[9]

In response to the shoot down of Malaysian Airlines MH17 on 17 July, on 30 July the EU and U.S, announced tough new sectoral sanctions against Russia, targeting oil and defense firms and bank transactions. Putin retaliated on 6 August by banning food imports from countries that had sanctioned Russia, and sent more military support to prevent the separatists in East Ukraine from being overrun. Putin and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko agreed the terms for a ceasefire in Minsk on 26 August 2014, but the fighting continued. Nevertheless, on 31 October 2014 Ukraine secured its winter gas supplies by agreeing to pay Russia $3 billion in arrears and a $1.5 billion prepayment for future gas supplies at $378/bcm. In November 2014 the Kyiv government stopped pension and welfare payments to the separatist regions (amounting to $2.6 billion a year. Russia started paying pensions in Crimea, but the residents of the separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk were out of luck).

A reaffirmation of the Minsk ceasefire in September 2015 finally saw an end to most of the fighting, although there was still no progress on implementing other terms of the deal, such as Kyiv granting autonomy to the separatist regions, or Russia allowing the Ukrainian government to regain control over the eastern border. Hence on 14 September 2015 the EU extended sanctions against 149 Russian individuals and 37 entities for an additional six months. The same month Ukraine managed to restructure $18 billion of international debts, with IMF assistance. Private lenders accepted a 20% haircut and linked repayments to future GDP growth, starting in 2021. (Ukraine’s debt was selling at 75 cents on the dollar at the time.) Russia insisted on treating its $3 billion loan as sovereign debt, and refused to accept any reduction in the principal. In September the two sides did agree on a price for winter deliveries of gas ($230/bcm), though the next month all direct flights between the two countries were banned. But by the end of 2015, Russia accounted for just 12% of Ukraine’s trade. In November Ukrainian and Tatar activists blew up power lines to Crimea, triggering extensive blackouts in Crimea. Moscow scrambled to lay undersea cables to replace some of the lost power. With Ukraine’s free trade agreement with the EU entering force on 1 January 2016, Putin announced that Russia would suspend its free trade agreement with Ukraine, and tariffs averaging 6% would be imposed on Ukrainian imports.[10] Russia claimed that it was concerned about the re-export of goods imported from Europe.

Meanwhile, Putin’s intervention in Syria in September 2015 added an additional burden to the military budget, and soured relations with Turkey. After Turkey shot down a Russian bomber on 24 November an angry Putin announced sanctions on Turkey—a ban on charter flights and tour groups, an end to visa-free travel, and suspension of work on the Turkstream gas pipeline and Akkuyu nuclear reactor. Turkey was Russia’s seventh largest trading partner, with $44 billion in turnover in 2014, and had not joined the sanctions regime against Russia. Turkey accounted for a large proportion of the fresh fruits imported into Russia in 2014—including grapes (48%), tomatoes (42%), citrus fruits (31%).[11] So any further deepening of sanctions on Turkish products would be a blow to Russian consumers.

The Elusive Pursuit of Diversification

The key danger is Russia’s heavy dependence on oil and gas exports, which account for 70% of exports and 50% of government revenues. Putin and Medvedev have tried to insulate Russia from the “Dutch disease” (an overvalued currency making Russian producers uncompetitive), by building up large reserve funds during the boom years and trying to prevent the overvaluation of the ruble. But they have little to show for their efforts to promote the modernization of the Russian economy through substantial investments in R&D.

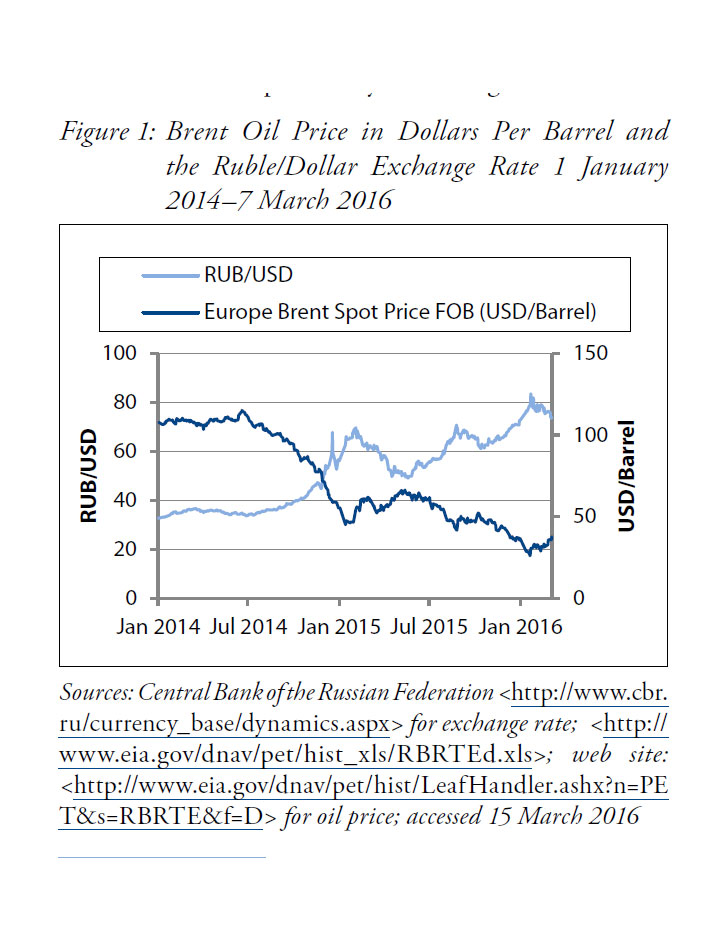

The chronic problem of oil dependency has become more acute in the past two years. The global market is saturated with oil due to the shale gas/tight oil revolution in the United States and Saudi Arabia’s determination to drive the price down and make those unconventional methods uncompetitive. After hitting a peak of $115 in June 2014, the oil price fell to an average of $38 in 2015. This caused the ruble to fall from 35 to the dollar in 2013 to 70 to the dollar in December 2015 (com- pared to an average of 26/$ over the past two decades) and 77 to the dollar in January 2016. This cost Russia $125 billion in lost revenues in the course of 2015, leading in turn to a contraction in imports and a slump in government revenues. In the first 10 months of 2015 imports were 38% down on the same period in 2014, and exports 34% down.[12]

The falling oil price was compounded by the economic fallout from Putin’s intervention in Crimea. Western countries imposed sanctions on selected Russian individuals and firms involved in Crimea in March 2014, and these were expanded in July to include sectoral sanctions on bank transactions and oil and gas technology imports.

Analysts disagree over how much impact the sanctions are having, with some arguing that the impact of falling oil prices and a depreciating ruble swamp the sanctions effect. The sanctions forced the suspension of offshore Artic oil projects by ExxonMobil (with Rosneft), Shell (with Gazprom Neft), and Total (with Lukoil). These projects might have been cancelled anyway due to the low oil price-witness Putin’s surprise decision to abandon the South Stream gas pipeline across the Black Sea in December 2014.

Austerity Economics Comes to Russia

The government deficit was 1.3% in the first 11 months of 2015 and is expected to run at 3–5% of GDP in 2016. The 2016 budget initially assumed an oil price of $50 a barrel, though by January 2016 Brent crude was trading at $30 and Urals blend at $27.[13] ($82 would be required for the government budget to break even). Gazprom’s average export price in 2015 was $252 per 1000 cubic meters, down from $352 in 2014.[14] The Ministry of Economics revised the 2016 projection to $40, and projected GDP growth of 0.7% in 2016 was revised to an 0.8% decline. Given the uncertainty over the oil price, in January finance minister Anatoly Siluanov announced that the 2016 budget will be revisited in April. A government meeting on 21–24 December asked ministers to begin drawing up across-the-board spending cuts of 10%, with exemptions for wages, pensions, and military spending. In contrast to the 2008 crisis, this time around the government has been unable to shield the Russian public from the impact of the economic turbulence. GDP fell by 3.8% in 2015 and few analysts expected growth of more than 1–2% in 2016.[15] Living standards fell 9% in 2015—the first time that real incomes have fallen since Putin took office in 1999.[16] Despite the negative growth, inflation ran at 15.5% in 2015 (up from 11.4% in 2014 and 6.5% in 2013). This despite the Central Bank sticking to a tight monetary policy, with the refinance rate pushed to 17% in November 2014, in an effort to stabilize the ruble (falling to 14% in March 2015). 22 million people (15% of the population) were below the poverty line by the end of 2015, with 2.8 million added in 2015.[17] In response to the pressures of the 2008 crisis, social spending as a share of the budget went from 9.1% of GDP in 2008 to 14.3% in 2015.[18] But the government no longer has the financial cushion to maintain that social safety net.

Despite these bleak results, at the June 2015 St. Petersburg Economic forum most government officials were avoiding talk of crisis, instead emphasizing that Russia was following its own “special path.”[19] In December 2015 Leonid Grigoriev, head of the government’s Analytical Center, went on TV to reassure the Russian public that the global oil price will bounce back to $80 in 2016, and urged “patience.”[20] In contrast finance minister Siluanov, speaking at the Gaidar Forum, warned of the potential for a catastrophic financial collapse on the scale of 1998;[21] while Sberbank head German Gref warned that “the oil century is at an end” and “all state institutions have to be reformed.”[22] Notwithstanding the “anti-crisis plan” launched in January 2015, Dmitrii Butin argues that the government really has no plan to deal with the current crisis, and has exhibited “strange passivity,” with the liberal-inclined bloc of economics ministers resisting calls for deficit spending.[23]

The potential silver lining to this particular cloud is that with the ruble at 70/$, Russian manufacturing and farming may be able to compete with Western imports. The government has been making some serious efforts to promote re-industrialization and reduce Russia’s dependence on imports. Government directive no. 98 of 27 January 2015 made import substitution a top priority, and on 31 March 2015 the Ministry of Industry and Trade published 18 import-substitution projects. Imports fell as a proportion of domestic spending from 26% 3/2013 to 19% in the third quarter of 2015. According to a new report from the Higher School of Economics, Russia did see some improvement in non-oil exports in the 2000s, rising from $10 billion to $50 billion 2000–2013, but they fell back to $30 billion in 2015.[24]

However, with stagnation in global markets, and continuing political uncertainties surrounding Russian sanctions, this is not a good time for entrepreneurs to be investing in new capacity. Despite the stimulus effect of the food counter-sanctions, by the end of 2015 agricultural output rose just 3.5%. Food production cannot be turned around overnight. Farmers were afraid of investing in new capacity in light of the fact that that the sanctions could be lifted at any moment, leading to a return of imported produce. In the short run, the decrease in food imports from the EU was partly offset by imports from Latin America, Turkey, Iran and China. There were also reports of European foodstuffs transiting Belarus and being relabeled for sale to Russia. Russia’s competiveness has been harmed by rising real wages, and a shortage of skilled workers. Manufacturing wage costs per hour (controlling for productivity) rose from an estimated $5 in 2000 to $11 in 2015—50% of the US level, but above Mexico ($9.33) or Taiwan ($8.45).[25]

Conclusion

Despite these mounting economic problems, it would be a reckless analyst who would suggest that they will lead to any significant political changes. The political system that Putin has engineered seems capable of riding out the storm.

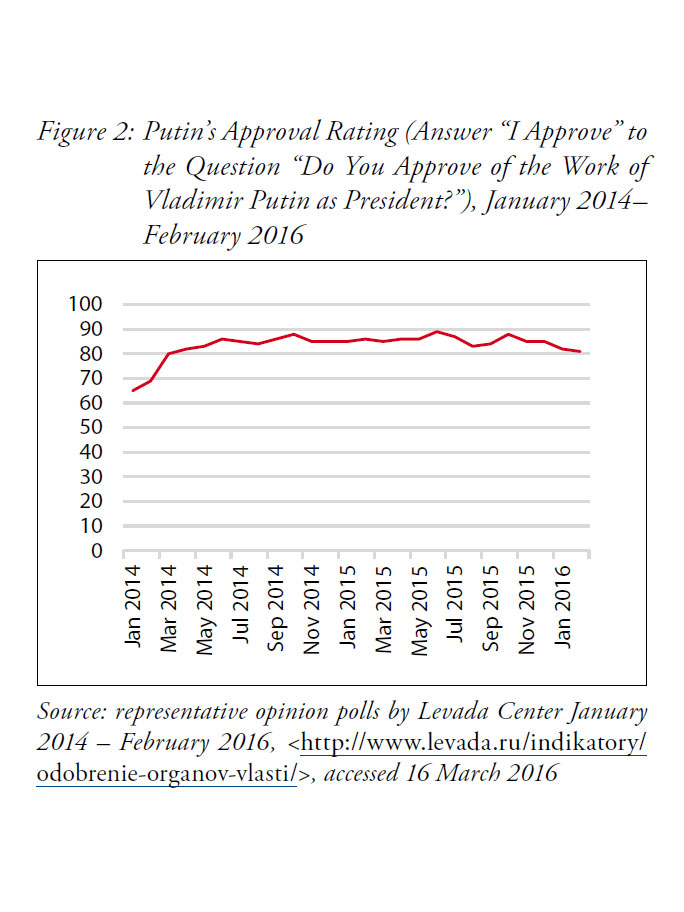

Putin’s approval rating jumped from 69% to 81% a month after the annexation of Crimea. The imposition of Western sanctions and Russian counter-sanctions did not dent his popularity—on the contrary, his approval rating rose to 88% by October 2014.[26] This was helped by the fact that most Russians apparently believe that the food embargo was imposed by the Western powers, not by Putin. But no one can say whether the popularity boost that Putin enjoyed after the annexation of Crimea can be sustained in the face of protracted economic hardship.

Notes

[1] external pagehttp://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/50864call_made

[2] There were 89 billionaires in Russia in 2014, down from 117 the year before due to the sanctions, the oil price slump, and the depreciation of the ruble. “The World’s Billionaires,” Forbes, 15 March 2015. external pagehttp://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/call_made

[3] Oliver Stuenkel, The BRICS and the Future of Global Order (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015).

[4] Remarks at the panel “BRICS 2.0,” Russia Direct, Washington, DC, 12 November 2015.

[5] external pagehttp://brics.itamaraty.gov.br/call_made

[6] external pagewww.en.brics2015.ru/documentscall_made

[7] Simon Evenett, The BRICS Trade Strategy: Time for Rethink (London: Global Trade Alert, 2015).

[8] Mikhail Molchanov, “Russia’s leadership of regional integration in Eurasia,” ch. 7 in Stephen Kingah and Cinita Quilicone (eds.), Global and Regional Leadership of BRICS Countries (Springer 2016).

[9] Margarita Liutova, “Ukraina razdelila tamozhennyi soiuz,” Vedomosti, 30 June 2015. external pagehttp://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2014/06/30/ukraina-razdelila-tamozhennyj-soyuzcall_made

[10] Vladimir Putin, Annual news conference, 17 December 2015.

external pagehttp://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/50971call_made

[11] Regnum.ru, 27 November 2015. external pagehttp://regnum.ru/news/economy/2022552.htmlcall_made

[12] external pagehttp://www.gks.ru/bgd/free/b04_03/IssWWW.exe/Stg/d06/260.htmcall_made

[13] Aleksandra Prokopenko, “Rossiiane budut bednet' bystree,” Vedomosti, 15 January 2016. external pagehttp://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2016/01/15/624101-rossiyu-zhdet-esche-god-retsessiicall_made

[14] Sergei Minaev, “Neft'; podskachala,” Kommersant, 21 December 2015. external pagehttp://kommersant.ru/doc/2877403call_made

[15] Ol'ga Kuvshinova, “Rossiiskaia ekonomika iz retsessiia vozvrashchaetsiav zastoi,” VedomostiI,24 December 2015. external pagehttp://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2015/12/24/622381-rossiiskaya-ekonomika-vozvraschaetsya-v-zastoicall_made

[16] Economics Minister Aleksei Ulyukaev, cited in Kommersant, 29 December 2015. external pagehttp://kommersant.ru/doc/2887949call_made

[17] Kuvshinova, op. cit.

[18] Andrei Sinitsyn, “Modernizatsia—ot zabora i do obeda,” Vedomosti, 13 January 2016.

[19] Grigorii Yavlinskii, “Reforma nevypolnyma,” Vedomosti, 29 November 2015.

[20] Leonid Grigoriev, ORT, 30 December 2015. external pagehttp://ac.gov.ru/commentary/07459.htmlcall_made

[21] Aleksandra Prokopova, “Minfin i Minekonravitiia ishchut sposobukak perezhit' 2016 god,” Vedomosti, 13 January 2016. external pagehttp://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2016/01/14/623922-minfin-minekonomrazvitiya-ischut-sposobi-kak-perezhit-2016-godcall_made

[22] Sergei Smirnov, “Rossia—proigravshaia strana,” Vedomosti, 14 January 2016 external pagehttp://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2016/01/15/624167-gref-rossiyacall_made

[23] Dmitrii Butin, “Spokoistvo po bednosti,” Kommersant, 25 December 2015. external pagehttp://kommersant.ru/doc/2884746call_made

[24] Aleksei Shapovalov, “Ni eksport, ni import,” Kommersant, 15 January 2016. external pagehttp://kommersant.ru/doc/2891421call_made

[25] Kathy Chu, “As China’s workforce dwindles,” Wall Street Journal, 23 November 2015.

[26] Levada Center. external pagehttp://www.levada.ru/old/26-03-2014/martovskie-reitingi-odobreniya-i-doveriyacall_made