An advocate of public space

Günther Vogt is one of the most sought-after landscape architects of our time. He has opened the eyes of an entire generation of architects to public space. After 18 years as an ETH professor, he is now retiring.

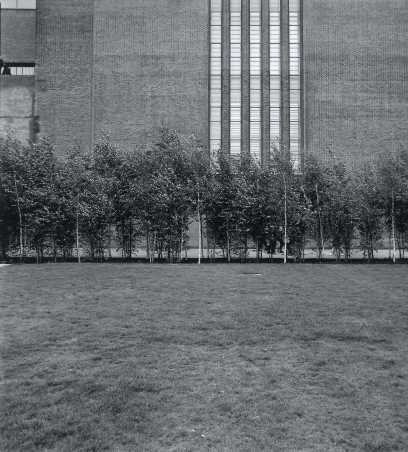

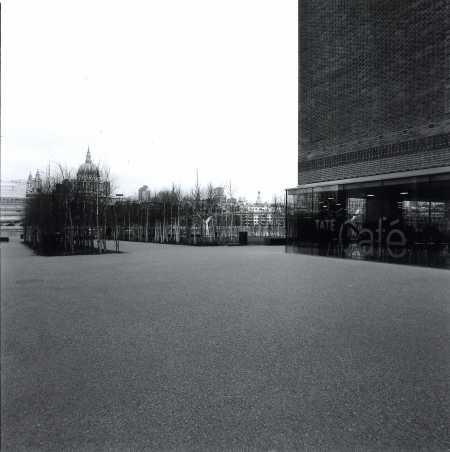

If you walk across the Millennium Bridge to the south bank of the Thames, you suddenly find yourself in front of a dense stand of birch trees framing a green meadow. It’s a place where people picnic and while away the hours. Behind it, the mighty brick building of the Tate Modern – a former oil-fired power station that was converted into a museum of modern art in 2000 – casts its shadow over the riverside promenade. The design for this small but famous piece of “nature” comes from one of the most sought-after landscape architects of our time: Günther Vogt.

“The forest is intended to refer to the location’s industrial past, as birch trees typically grow on industrial wasteland and often near rivers,” Vogt explains. For over 20 years, this Liechtenstein native has been designing gardens, parks and landscapes all over the world – including the gardens of the Eiffel Tower, the outdoor areas of the Allianz Arena in Munich and the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, as well as the Masoala Hall at Zurich Zoo. And for 18 of those years, he was Professor of Landscape Architecture at ETH Zurich. He retired at the end of July and is now Professor Emeritus.

The birch garden at Tate Modern. (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

The birch garden at Tate Modern. (Photograph: Christian Vogt) The gardens of the Eiffel Tower. (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

The gardens of the Eiffel Tower. (Photograph: Christian Vogt) The gardens of the Eiffel Tower. (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

The gardens of the Eiffel Tower. (Photograph: Christian Vogt) The outside area of the Allianz Arena. (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

The outside area of the Allianz Arena. (Photograph: Christian Vogt) The Masoala Hall at Zurich Zoo. (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

The Masoala Hall at Zurich Zoo. (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

At home walking

Vogt’s departure from ETH Zurich was atypical: instead of a farewell lecture, he invited people to take a walk from the Polyterrasse in Zurich along the River Limmat to Fahr Abbey. From the city out into the country, past beautiful places like the Josefwiese city park, but also less inviting places like a motorway bridge. For Vogt, both belong to what he calls the urban landscape.

Such walks have a special meaning for him: “Going for a walk is a chance to collect images that I can draw on when designing.” The process of walking is what creates Vogt’s inner archive. And this goes back to his childhood.

Botanical backpack porter

At a young age, Vogt developed a fascination with plants of all kinds. As a nine-year-old, he was allowed to accompany the experienced botanist Heinrich Seitter on countless forays through the countryside. “I carried his backpack for him, and soaked up everything he said about plants.”

Vogt started horticultural school in Oeschberg in the canton of Bern at the age of 16; by then he could already draw on considerable botanical knowledge, which he steadily expanded in the years that followed. His inner archive grew and grew.

Kienast and Vogt

Vogt then went on to study landscape architecture at the then Intercantonal Technical College in Rapperswil, where he found a mentor and companion in Professor Dieter Kienast. In 1995, the two set up a joint office. “In the beginning, we didn’t have much to do, so we had a lot of time to talk about landscape architecture in depth,” Vogt recalls.

For the young landscape architect, this dialogue with the older and more experienced Kienast was formative. He would never work so intensively with another person again.

“Open spaces are a city’s most important resource.”Günther Vogt

But the working partnership with Kienast came to a tragic end far too soon: he died in 1998 after a brief but intense illness. “Dieter’s death was a turning point. My most important sparring partner was suddenly no longer there. I had to rebuild everything and expand the circle of people I could talk to."

Focus on larger scales

Two years after Kienast’s death, Vogt opened his own office. From then on, his projects focused primarily on public spaces. He was usually concerned with large-scale projects that go far beyond individual building plots. Regardless of whether he is designing a park or an entire district, the main question is always the same: In the public space, what is the relationship between this place and the city and its culture? For Vogt, understanding the context is the basis for every design.

In West London, for example, he wants to transform the roof of a huge industrial gravel quarry into a public park that blends into the Green Belt around the city. And in Hamburg, Vogt is designing the outdoor areas for a new district on the Grasbrook peninsula: parks, promenades, squares, street spaces and courtyards together form a new urban landscape between the river and the port, integrating the port area into Hamburg’s urban fabric.

In Hamburg, Vogt is designing the outdoor areas for a new neighbourhood on the Grasbrook peninsula. (Photograph: Herzog und DeMeuron /Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten)

In Hamburg, Vogt is designing the outdoor areas for a new neighbourhood on the Grasbrook peninsula. (Photograph: Herzog und DeMeuron /Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten) Parks, promenades, squares, streetscapes and courtyards together form a new urban landscape between the river and the harbour ... (Photogaph: Herzog und DeMeuron /Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten)

Parks, promenades, squares, streetscapes and courtyards together form a new urban landscape between the river and the harbour ... (Photogaph: Herzog und DeMeuron /Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten) ...which integrates the harbour area into the urban fabric. (Photograph: Herzog und DeMeuron /Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten)

...which integrates the harbour area into the urban fabric. (Photograph: Herzog und DeMeuron /Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten)

Open spaces: A city’s most important resource

In such large-scale projects, the landscape architect increasingly acts as an urban planner, taking into account social, economic and ecological issues of urban coexistence as well as vegetation and topography. According to Vogt, the difficulty lies in reconciling the needs of very different users whilst at the same time creating an atmospheric space in which people will still feel comfortable in 30 years’ time.

Vogt sees open spaces as a city’s most important resource. That’s why he’s critical of the tendency to privatise public space: he feels urban planning must not degenerate into the management of residual areas. Only with sufficient open and green spaces can cities withstand climate change and remain liveable in the future. “In some metropolitan areas,” he points out, “we’ll have to create actual ventilation corridors to channel fresh, cold air into the city centres.”

Uncovering nature

With his designs, Vogt repeatedly succeeds in bringing out the natural characteristics of a place and making them tangible. One example is the Novartis Campus Park in Basel, where he has created deeply carved paths from exposed river sediment. This gives rise to an artificial landscape between the upper parts of the park and the Rhine, providing a stage for “nature”.

-

Novartis Campus Park in Basel. Exposed river sediments form a deeply incised hollow path. (Photograph: Christian Vogt) -

The Novartis Campus Park in Basel forms an artificial landscape that provides a stage for "nature". (Photograph: Christian Vogt)

Vogt’s landscapes and parks showcase not only his knowledge of plants, hydrology and geology, but also his sense of cultural context. “People’s understanding of what a landscape is varies greatly from country to country,” he says. For example, when Vogt learned that many British people work at the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, he suggested that the outdoor areas should be laid out with lawns rather than paths. Much to employees’ delight: “People from Great Britain truly have an erotic relationship with lawns,” Vogt offers in explanation of this positive reaction to his plans.

-

Both images show the outdoor area of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. (Photograph: Florian Holzherr) -

Collaboration with artists

In 2012, Vogt was awarded the Prix Meret Oppenheim by the Swiss Federal Office of Culture for his successful combination of landscape architecture and art. There was particular praise in the media for a series of exhibitions and interventions with the Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson.

At Kunsthaus Bregenz, the two brought simple natural phenomena such as fog, earth and water into the museum. In Ebeltoft, Denmark, they used round mirrors that reflect the sky to recreate the appearance of a lost glacial landscape. And in Basel, they flooded the Fondation Beyeler art museum. Almost a dozen aquatic plant species floated gently in the bright green water. “It was all new territory for Olafur and me,” Vogt says. “He went into the landscape as an artist, and I went into the museum as a landscape architect.”

Taking responsibility for public spaces

When Vogt joined ETH Zurich in 2005, he was only the second professor of landscape architecture at the Department of Architecture after Christoph Girot. Together, they were committed to ensuring that architecture, urban design and landscape architecture are taught together. They founded the Institute of Landscape Architecture and, after years of effort, succeeded in introducing a separate Master’s programme in Landscape Architecture in 2020 – the first at a Swiss university.

In his teaching, too, Vogt focused on large scales and public spaces. He has made an entire generation of architects at ETH Zurich aware that they must take responsibility for public space, think beyond the individual plot and understand a place within its larger context.

Vogt was known among his students for his open and inquisitive nature – and for good food. To loosen up discussions with his students, he would regularly gather them around the dining table in his office. “Cooking, eating and drinking together created a family atmosphere and eased some students’ fears and insecurities,” Vogt says.

Now that Vogt has retired, ETH Zurich has lost a pioneer of Swiss landscape architecture. But he certainly won’t get bored even though he’s no longer teaching. With offices in Zurich, London, Paris and Berlin, Vogt still has his hands full. He has deliberately chosen not to leave his students and his successors any good advice. Because every generation has to go its own way, just as he has done ever since he was young.