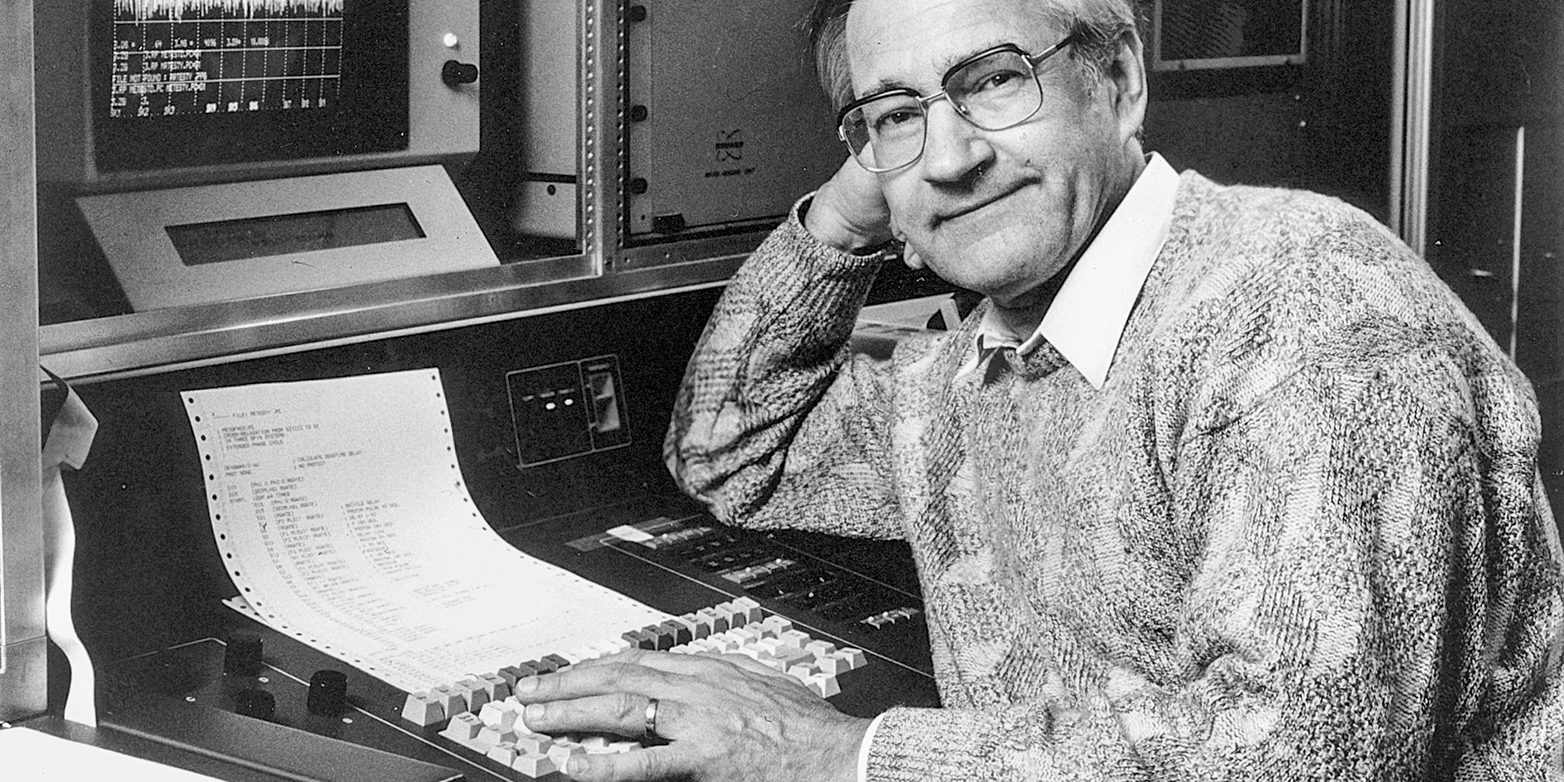

Richard Ernst (1933-2021)

ETH Zurich mourns the death of Richard Ernst, ETH professor emeritus and Nobel laureate. Alexander Wokaun did his doctorate under him and remembers him - a personal obituary.

It was with great regret and deep sadness that I learned of the death of Richard Ernst. Richard was more than just a doctoral supervisor to me; he was my mentor and fatherly advisor. His pioneering research into nuclear magnetic resonance laid the foundation for the later development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Far beyond the world of analytical chemistry and structural research, his findings thus live on every single day in hospitals and radiology practices around the world.

I first met Richard when I was studying chemistry at ETH Zurich. At the time, I was attending, as he had done before, lectures by professors of physical chemistry such as Hans Heinrich Günthard and Hans Primas. I was so impressed by Richard’s own lectures on the principles of physical measurement and the fundamentals of nuclear magnetic resonance, by the lively and spirited manner in which he delivered them, and by his personality that I approached him in the spring of 1974 about a topic for my thesis.

That autumn, I was granted the opportunity to join Richard’s group as a doctoral student. In his passionate commitment and absolute dedication to science, he set the highest of standards for himself, making him a role model for everyone in the group without asking too much of them. It would often happen that, after an afternoon spent in discussing a scientific problem, Richard would come back the next morning with a solution formulated in his neat handwriting, having worked on it late into the evening or even during the night. Our Monday group seminar was another example – if one of the doctoral students was unable to attend and present, Richard would step in and himself give an exposé on the topic foreseen.

Those years between 1974 and 1978 were incredibly exciting. It was during this time that the fundamental advances were achieved that would allow two-dimensional spectroscopy to acquire the pre-eminent position it now enjoys in chemistry, biology, and medicine. In neighbouring laboratories, my fellow postgraduates from the group were working on increasing the sensitivity of MRI techniques. While writing my own thesis on a different aspect of multidimensional spectroscopy, I was able to witness expectations and breakthroughs in imaging technology first hand. Successfully defending my thesis to complete the project marked a key milestone in my life.

And it was on Richard’s advice – another testament to his excellent mentoring skills – that I devoted my attention to a different field of experimental methodology during my postdoctoral stay in the United States. This is how I became involved in laser spectroscopy, which then also formed the basis of my habilitation in another team at ETH Zurich between 1982 and 1986. A book we were writing together meant that Richard and I remained in touch during this period as well.

In 1991, when I was teaching at the University of Bayreuth, the news that Richard had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry brought great joy to the research community, not least to me. I also have fond memories of a seminar week in Ticino some time afterwards, when Richard invited all his former doctoral students and colleagues to join him for a review of the developments that had taken place over those key years. As we reflected, it was remarkable to see the many different career paths the graduates of the group had chosen – another sign of the solid and diversified knowledge base Richard had given us to prepare us for our professional careers. He, too, branched out into other areas, including classical music and especially Tibetan art – a field in which he became a great connoisseur of the mythology and symbolism behind the Tibetan paintings on cloth known as thangkas.

The Nobel prize marked the beginning of a new era in Richard’s work. After everything he had achieved, he was more than deserving of the accolade, yet he regarded it as more of a calling to use the influence it brought to advocate a subject that had always been close to his heart. With boundless energy, he devoted articles and lectures to scientists’ social responsibility, and to how important it was for them to reflect on the meaning and consequences of their work. Testing the limits of his physical endurance, he travelled widely to present these ideas at international conferences and as a guest speaker at research institutes on all continents. Richard lobbied fervently to keep the administrative burden on Swiss university staff low and to preserve academics’ freedom to develop new, creative ideas.

At the same time, he took his responsibilities in university administration and as an advisor on numerous committees very seriously, fulfilling them with the same diligence as he did his scientific work. After his retirement, Richard continued to pursue his interest in the history of arts. He could now devote more of his time to analysing the pigments used in the thangkas, narrowing down the place and time of their creation, and developing his restoration skills to the point that he was able to restore age-dulled and damaged paintings to their original radiance.

With Richard’s passing, we have lost a dedicated polymath, a man to whom ETH Zurich, science, and society owe a huge debt. His passion for chemistry and its meaningful application for the benefit of society is a shining example that will continue to serve as a model for us all.

This text is an abridged and edited version of the epilogue to the external page Autobiography of Richard R. Ernst, published in German by Hier und Jetzt. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.