Strategies for Sustainable Business

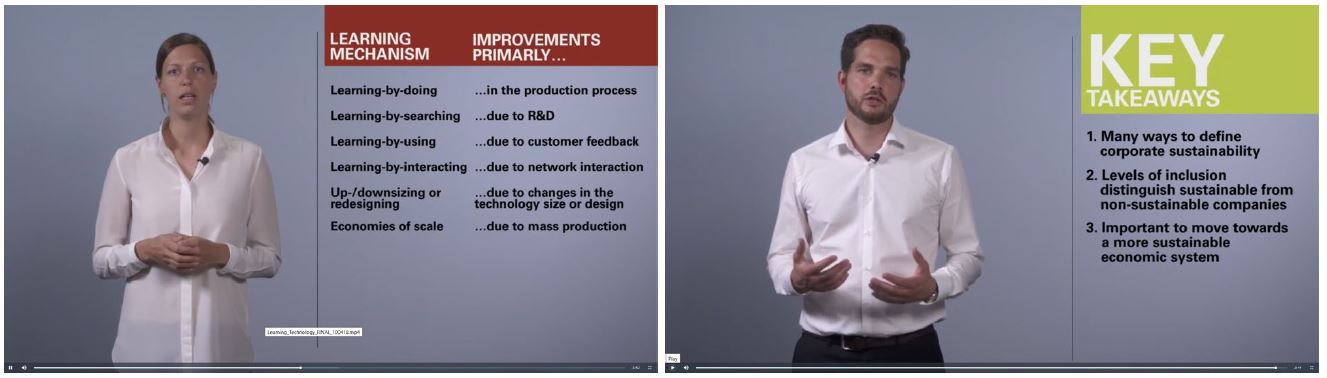

Before the time of distance learning, I taught Strategies for Sustainable Business as a block course over three full days (see Figure). My teaching style does not rely on frontal lecturing. Instead, I apply highly interactive didactic formats such as Harvard-style case studies with teamwork, computer simulations and negotiation games, discussions with industry guest speakers, and in-class conversations. Before the lock-down, the course was highly interactive, with long and intensive days aimed at an immersive learning experience where students worked together and were not distracted by other obligations.

Implementation of the course during the time of distance learning

The first course day in 2020 was scheduled for March 27. This date was less than two weeks after ETH announced emergency operations. At that time, I had no experience with online teaching, little experience with Zoom (or other video conferencing software), the functions available there (e.g., polls, breakout rooms) and other digital tools. Changing the original format of the course into a purely online format was challenging for three reasons:

1. How to translate the interactive elements into an online format?

2. How to maintain focus and concentration over such a long time?

3. How to maintain contact with the participants?

It was clear to me that—if I wanted to achieve the same learning objectives—redesigning the course for remote teaching would require training of the participants and myself while the course was running.

I transformed the course in three steps.

1. I directly translated interactive elements into online formats. For example, I often use “Yes-No” survey questions at the beginning of a course to show students that they are invited to and need to actively participate. In the online format, I would use the Zoom poll function to directly translate this format. Another format that I directly translated were teamwork exercises for which I used breakout rooms. More difficult to translate were collective brainstorming exercises. In-class, I would ask students to document their ideas on post-its and to structure their ideas on a whiteboard. In the online format, I used a GoogleDoc for participants to write down their ideas (examples available in the Appendix). Since everyone worked on the online documents simultaneously, we were able to observe the collective brainstorming process and to begin structuring ideas.

2. When I could not directly translate formats into online elements, I reconsidered the learning objectives and re-adjusted the teaching format.

- For example, in the original format, I would spend 15-20 min at the beginning of each class, to “set the stage” and ensure that all participants had the same foundations for the subsequent discussions. For the online format, I “outsourced” this preparatory work by asking the class to complete short six-sentence arguments before each session (examples available in the Appendix). Already before the pandemic, I used the six-sentence argument (6SA) format in another course to teach students to formulate a convincing argument. Yet, for the online format of this course, the tool brought two additional benefits: participants were able to prepare the material asynchronously whenever it suited their schedule, and when they joined the course, they arrived prepared.

- I also found it difficult to directly translate reflection exercises at the end of each session. During the first course day, I quickly realized that towards the end of each class, participants would lose focus and concentration. In the original in-class format, I would spend a lot of time at the end of a session to discuss together with the participants what they had learned, what surprised them, and what they agreed or disagreed with. Additionally, I would spend time with the participants to discuss the implications of the learnings for their own work. This section seemed too lengthy in an online format, so that I designed reflection exercises which the participants could complete after each session whenever it suited their schedule (examples available in the Appendix).

3. I adjusted the course design to the overall physical well-being of the participants and myself. Most of them were sitting alone at home, quarantined in hotels, or traveling to their home countries. At the same time, all were trying to learn and participate in an online class. This new reality asked for more asynchronous delivery formats to shorten the overall time that we spent as a group, synchronously in the (online) classroom while ensuring the same learning experience. I also schedule more but shorter breaks to reduce digital overkill and zoom-fatigue. Similarly, I introduce additional off-line and off-screen elements (asking participants to step away from the computer), such as readings or individual brainstorming sessions (of about 10-15 min each). These early, ad-hoc experiments of mixing synchronous vs. asynchronous and online vs. in-class formats provided important learnings for innovative and well-balanced remote teaching.

Course description

Overall concept of the course before the pandemic - during - after

Before the pandemic, the course Strategies for Sustainable Business used to be a three full-day block course. The design combined various teaching formats such as case studies with teamwork, computer simulations and negotiation games, guest speakers from industry, and in-class discussions. The long and intensive days were highly interactive and aimed at creating an immersive learning experience where students work together and are not distracted by other obligations.

During the pandemic, I redesigned the course into an online, low-tech digital format for remote teaching. In addition to the challenges of transforming the course into an online format, I asked myself: How can I maintain the participants’ and my own attention over a long course day? How can we connect and learn together?

Drawing on what I think are my core responsibilities as a lecturer at ETH, I redesigned the course in three steps. First, I translated interactive teaching elements into an online format (e.g., using breakout rooms for teamwork). Second, if a direct translation was not possible, I reconsidered the learning objectives of a session and re-adjusted the format towards remote teaching.

Third, I adjusted the overall course design to the new reality: I created more asynchronous formats, changed the ‘rhythm’ of the course including more and shorter breaks, and introduced more off-line and off-screen elements.

After the pandemic, the course still includes the same content and learning objectives. However, the concept has changed in three ways. First, it optimizes the use of online and offline, synchronous, and asynchronous teaching formats, to combine the best of both worlds. Second, the teaching formats are aligned with the specific course content and learning objectives. Third, the workload for the students is better distributed, shifting preparation and reflection exercises to before and after the course. Together, the new concept allows for a unique and improved learning experience.