Give and take in a local electricity market

In the "Quartierstrom" project, ETH Zurich has joined forces with partner companies and universities to conduct field trials on a local electricity market for the first time. Christian Dürr from the Wasser- und Elektrizitätswerk Walenstadt (WEW) shares his experience as an SME in this project.

What was the Quartierstrom project about?

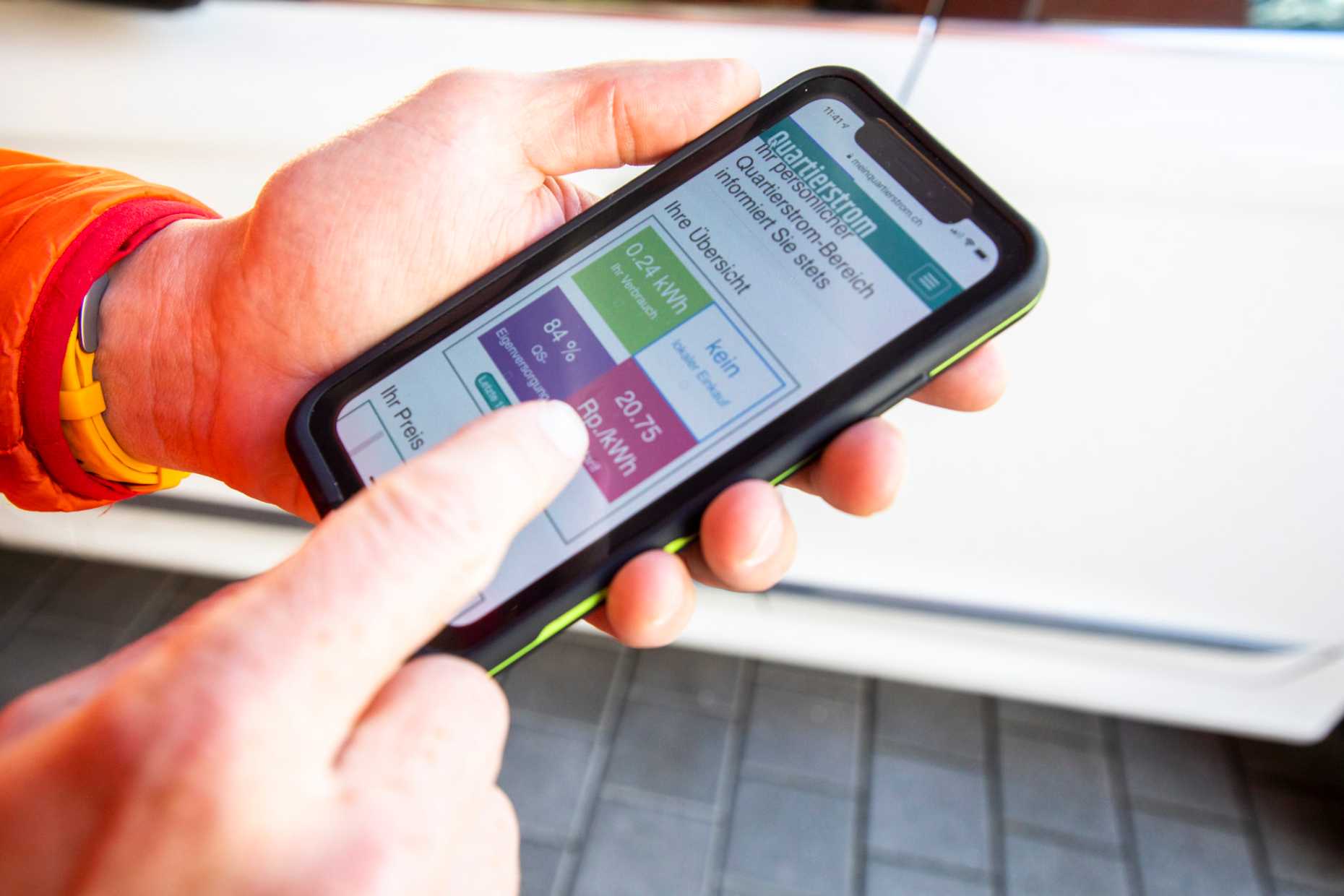

In this project, 37 residents of the Schwemmiweg area formed an electricity-prosumer community. 28 participants have solar panels on their roof, 9 were mere consumers. The participants of the community produced electricity, sold it to their neighbours independently or bought solar power from other members of the community. All participants could trade electricity with an app on their mobile phones - the secure and anonymous data transfer was guaranteed by a blockchain. The WEW was also a participant in this local market and supplied grid power when needed.

The project enabled households that produce solar power to trade it directly at the local market for the first time. It was the first blockchain-based electricity market in Switzerland. Prosumers were free to set the price for their solar power within a pre-set range.

How did the cooperation with ETH Zurich come about?

Doctoral students at ETH Zurich approached us. We believe that our business activities must be sustainable for both nature and the wallet, so we were excited about the project. We have been installing photovoltaic systems for our customers since 2010. To be precise, we have installed around 150 systems in our supply area alone. This means that about 4 percent of our 3500 customers are already producing solar electricity. As an energy supply company, we would like to be part of this change and we believe that solar panels and thus in-house production will increase. Consequently, new laws and regulatory changes will be needed. These changes will affect us directly. We were also interested in the pricing: how do you regulate this financially if we provide infrastructure for the in-house producers; what are the levies in a local 'micro-market', etc.

What was your role in the project?

Our contribution was mainly labour; for example, we installed the required smart metres free of charge. In total, we provided labour to the value of about CHF 40,000.

To test the local market, it was important that our grid infrastructure was available for the transfer of electricity. We also took an active part in the local test market by buying surplus solar power and supplying grid power when the local area was producing too little.

To what extent did the Walenstadt Water and Electricity Board need to balance the supply? What was the self-sufficiency level of the community?

The project participants were 35 percent self-sufficient. Before the local electricity market came into play, the degree of self-sufficiency among photovoltaic system owners was no more than 19 percent (this was the case for single-family homes).

What were the benefits of this cooperation?

We are very satisfied with both the project's progress and the results. It was a perfect match in terms of the people involved. We feel inspired to do more and are thinking about operating a local market permanently. As a small, local energy provider, we took a pragmatic approach to the project, sometimes turning a blind eye or even two. This would probably not have been possible with a larger energy supply company, where there is more concern about regulations. All in all, we believe that SMEs like the WEW can run exciting projects with institutions such as ETH Zurich.

Was the blockchain approach suitable for transactions in the local market?

It was important to try out the blockchain in such an application. We now know that it is not necessary in the energy sector. The disadvantage is that large amounts of data have to be transferred, which can consume the power savings straight away. The advantage is the high level of security. However, customers trust the Swiss power companies and most of them know each other, so a blockchain is probably not necessary. At best, it could be interesting as a kind of label to declare where the electricity comes from. Overall, its application is probably more in demand in the banking world, where mistrust is greater because people do not know each other.

In the extended follow-up project, in which we also want to be involved, the local market will probably be operated without blockchain.

Other project partners included BKW and SBB.

Both were financially involved in the project, but acted more as observers. They were mainly interested in the results of the experiment: how would a local electricity market function? SBB wanted to know whether local electricity markets with their in-house producers could be considered for their properties in the future.

The project “Quartierstrom” was launched in September 2017 by the Bits to Energy Lab, a joint research initiative of ETH Zurich (Distributed Systems Group, Institute for Pervasive Computing & Chair of Information Management) together with the University of St. Gallen (Institute of Technology Management). The field phase lasted from March 2019 to March 2020 and was supported by the Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE. Apart from WEW, BKW and SBB were also involved in the project.

Contact / Links:

Do you want to get more "News for Industry" stories?

external pageSubscribe to our newslettercall_made

external pageFollow us on LinkedIncall_made

Are you looking for research partners at ETH Zurich?

Contact ETH Industry Relations