Allergic to monocultures

In the 1980s, Hans Herren performed an agricultural and ecological miracle in Africa that saved the lives of approximately 20 million people. Today he’s no longer waging war on mealybugs, but on the influence of the agricultural industry and on short-term thinking.

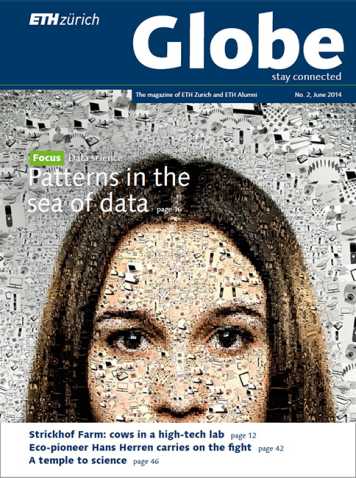

This article has been published in Globe, no.

2/June 2014:

Read the magazine online or subscribe to the print magazine.

Hans Herren seems impatient and tense. Like someone who is running out of time. And time is what he urgently needs in order to put into practice his convictions of thirty years’ standing: that organic farming can be a remedy for hunger and hardship. It is difficult to catch this perpetual jetsetter for a conversation. Herren commutes between continents and is forever donning a different cap: in Rome he conducts meetings with the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), for which he spent five years coordinating the most comprehensive world agriculture report to date and where his wife, Barbara, an American ecologist and project coordinator, also works.

In Zurich he visits his “Biovision” staff, a foundation he set up sixteen years ago to promote organic agriculture in East Africa. And in his office at the Millennium Institute in Washington D. C. he has been preparing workshops that he will shortly be giving for government representatives in Africa. “I have to keep on my toes and maintain the tension”, Herren confesses. “Otherwise, the tiredness will soon catch up with me.”

With eco-activists in America

Herren is at home everywhere and nowhere; a citizen of the world whose Swiss German dialect by now sounds American and who seems to spend more time in the air than in any particular nation. Besides, his heart was never really in Zurich, despite having spent eight years at ETH – four as a student of agricultural engineering, then four as a doctoral student on a quest to find a biological control for the larch bud moth pest. For him, California is the closest thing to a home. He bought a house and land there some twenty years ago, and since then spends his days off in the Capay Valley, trading in his suit and tie for wellies and an apron and indulging in his passion as a hobby wine-grower in his own vineyard.

"We managed to increase crop yields with the same varieties by adjusting the methods."Hans Herren

Herren first came to California in 1977 to do a postdoc in Berkeley, where he conducted research in the field of entomology and integrated biological pest control in Robert van den Bosch’s group. Van den Bosch was a pioneer in the field and, at the same time, a diehard eco-activist and adversary of Norman Borlaug, the father of the “Green Revolution.” Global hunger was to be wiped out through the mass use of artificial fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides, or so his popular opinion went anyway. Under van den Bosch, Herren not only learnt a lot about biological pest management, but also about politics and lobbying in American companies.

"It was high time I continued my fight in politics."Hans Herren

There were practical reasons behind his subsequent departure for Africa: “My National Science Foundation grant had run out, I couldn’t stay in the USA and I knew that there was no longer any interest in biological pest control in Switzerland”, Herren explains. He spotted an opportunity to put his knowledge into practice when he saw a job vacancy at the Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Ibadan, Nigeria: a mealybug introduced from South America in the early 1970s was threatening the cassava harvests in large parts of Africa.

“Even though I had long hair and a Ho Chi Minh beard back then, I managed to win over the International Fund for Agricultural Development in Rome with my idea.” With 250,000 dollars, Herren set up a mobile lab in a minibus and drove off to Mexico in search of the useful creature that keeps the cassava mealybug in check in South America. Two years later, he discovered the ichneumon fly Anagyrus lopezi in Paraguay, which was subsequently studied in London under quarantine. Herren set up a research station in Cotonou, Benin, where his team bred millions of ichneumon flies in greenhouses and devised a system to “spray” the insect by plane. Over ten years, Herren’s brigade released around 1.6 million ichneumon flies in thirty countries. By 1992 the battle had been won: the cassava had recovered and a famine had been averted. Moreover, the final studies in 2003 revealed that the effect was long-term; the friendly fly is still keeping the pest at bay to this day.

Harvests five times greater thanks to organic farming

Herren had proved for the first time that ecological pest control works. Economists subsequently estimated the benefit to African agriculture at 14 billion dollars. As Director of the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology in Nairobi, Herren and his team developed a series of methods for smallholders from 1994 to 2005, including the “push & pull” system. This involves using the fragrance of desmodium, a ground-covering bean plant, to oust the stalk borer that kills off maize and sorghum fields in Africa (this is the “push”), while farmers also plant napier grass around the fields, the scent of which attracts the stalk borers (the “pull”) and captures them in its sticky blades. Moreover, desmodium binds nitrogen, thereby improving the soil quality and elbowing out the striga weed. “The advantages are well documented. We managed to increase crop yields with the same varieties by adjusting the methods.” Today, 40,000 farmers in Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda successfully produce organically, explains Herren. On a continent with a population of over 1 billion, that’s a modest number and begs the question as to why ecological methods are not more widespread. “Because the agricultural industry can’t earn any money with organic farming”, answers Herren indignantly.

Efforts at persuasion using dynamic models

Herren is convinced that “too many good initiatives are blocked by industry and politics.” Which is why, in 2005, he swapped his office in Kenya for one in Washington D. C., where he combines science and politics as Director of the Millennium Institute, a platform for system-dynamic modelling. “It was high time I continued my fight at the top, in politics.” He explains how this works based on the current project “Changing Course in Global Agriculture”: together with DEZA and his foundation Biovision, the “Millennium Institute” brings representatives from politics, science, civil society and industry to the table in Senegal, Kenya and Ethiopia. Herren and his experts use models to simulate scenarios as to how the nation’s objectives can be achieved. Based on the simulations, he hopes to get the decision-makers on board with his vision.

Would it be easier or more difficult for an “ecofreak” with long hair and a beard to repeat his career path today, 35 years after the launch of his campaign against the cassava mealybug? “More difficult!” declares Herren. He’s convinced of it. “Agricultural research is increasingly being shifted to the private sector, where no-one is interested in ecological pest control anymore.” He claims that biotechnology and molecular biology have supplanted all other fields – in both research and teaching. Herren remains allergic to monocultures to this day, regardless of whether they are intellectual or biological in nature.

About Hans Rudolf Herren

Hans Rudolf Herren grew up on a farm in Unterwallis. After attending agricultural school, he took his secondary school certificate and embarked on a degree in agricultural engineering specialising in plant protection at ETH Zurich in 1969. Following a postdoc at the University of California in Berkeley, Herren ran two research institutions in Africa. He received the FAO’s World Food Prize in 1995 and the Right Livelihood Award in 2013 for his successful project against the cassava mealybug. Herren has been President of the Millennium Institute in Washingto D. C. since 2005.