Unclear climate targets

Among the general public, the two degree target is perceived to be a universally agreed limit that scientists regard as a safe level that avoids dangerous climate change. This is an erroneous perception. The two degree target is less clearly defined than generally assumed, and it is even less clear how we will meet it.

For a few days, negotiations have been underway in Paris to determine the next global agreement on mitigating climate change, which is to replace the Kyoto Protocol. The declared long-term objective is to limit warming of the earth’s atmosphere to two degrees relative to the pre-industrial era. But how clear is this climate target? And is it a suitable target? These questions are addressed in our recent perspective article ‘A scientific critique of the two-degree climate change target’ in the journal Nature Geoscience. [1]

Two degrees as an (un)safe guard rail

Although the two degree target is well-established politically and among the wider public, it is often misunderstood. The prevailing view is that climate scientists have identified two degrees as a safe target, which, if met, will prevent dangerous climate change. This is incorrect: no scientific research has ever described two degrees of warming as safe.

First, no clear boundary exists between dangerous and safe. In some places and regions, climate change is already a problem; in others, it will barely be a problem even at 3 degrees. Second, it is impossible to make a purely objective assessment. Here is a simple thought: would it be dangerous if the polar bear were to die out? The polar bear does not have any effect on our lives and, for many of us, probably does not score highly in a cost–benefit analysis. For many people, however, it has an emotional or intangible value. Similarly, what is seen as dangerous is always a value judgement and depends – like beauty – on the eye of the beholder. The way we perceive risks is personal: some people think skydiving is great fun, while others would never even consider it.

In our opinion, the global surface temperature is indeed the best measure for a climate target: temperature increases and total CO2 emissions show a practically linear relationship, and each temperature target is therefore associated with a certain emissions budget. A safe target value, however, is almost impossible to identify.

Many questions remain unanswered

It is not clear how gradual the effects will be at values of about 2 degrees. Would 10% above the target simply be 10% worse? Do localised tipping points exist in the system and would they occur suddenly, for example as a spontaneous change in oceanic circulation, the collapse of an ecosystem, or the thawing out of permafrost? And what probability of meeting the target are we looking for? The approaches to a reduction of CO2 discussed today typically have a probability of up to 33% that we will miss the target. However in aircraft or nuclear power plants, error rates of much less than one in 1,000 are considered acceptable. No one would get on a plane that had a 33% chance of crashing. What level of certainty do we want – or need – that we will not exceed the target? This too is a normative question, and one that science alone can not answer.

1.5 degrees as an alternative?

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) recently completed a comprehensive evaluation as to whether the two degree target should be tightened to 1.5 degrees (see the blog post of Andreas Fischlin). The report concluded that two degrees of warming is anything but safe, and that we should try to stay as far below that level as possible. Although this conclusion may be justified in terms of the impending effects, let us be under no illusion: 1.5 degrees can most likely be met only by temporarily exceeding the target and then by achieving negative emissions. Negative emissions mean that more CO2 is removed from the atmosphere than is added – i.e. carbon sequestration surpasses anthropogenic emissions. A problem with this is that we are living at the expense of future generations, who will need to ‘recapture’ our CO2 with technologies that either do not exist yet, or are simply too expensive. In other words, it is a dangerous speculation. Moreover, it is not clear how gradually the climate system will respond, or whether all the effects are reversible.

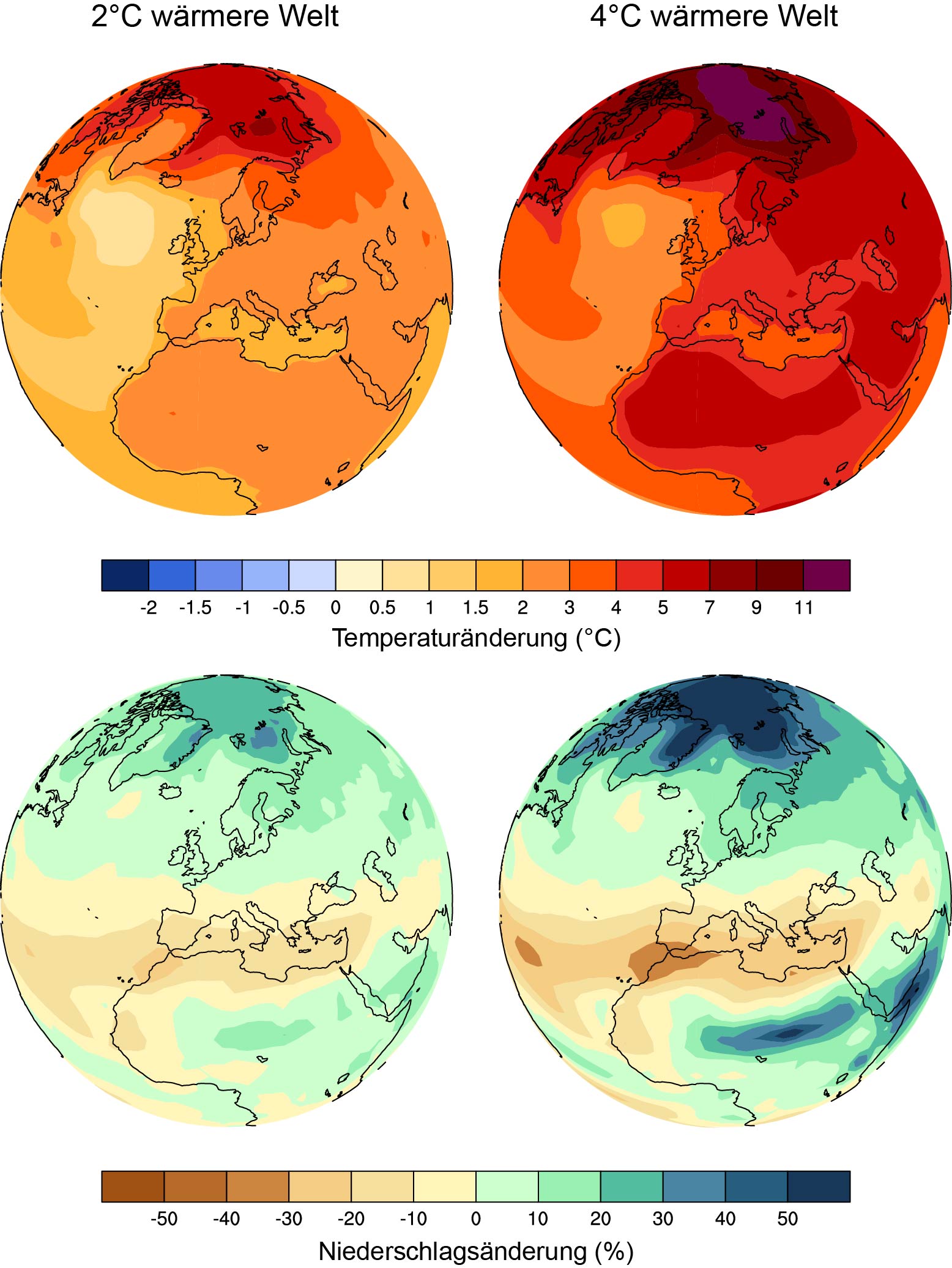

To a certain extent, science is indeed able to determine the effects of 1.5 degrees, 2 degrees or other climate targets, and to compare these with a 4 degree world without climate protection. It’s therefore possible to make many statements in objective terms; however, like a speed limit of 120 km/h on the motorway, two degrees of warming is also a normative target that we have set ourselves as a society. It is a compromise between costs, benefits and risks, shaped by personal (and collective) perceptions and by a demand for fairness. After all, it is not us but those already living in poverty who will feel its effects first and most severely.

Either way, we must act

The reality is that our CO2 emissions are currently nudging the upper margin of scenarios without climate protection, and that the reductions proposed for Paris are not enough to meet the two degree target [2]. No one believes that the Paris talks will see our remaining CO2 budget divided up. It would be a major success if, for the first time, an agreement could be reached with the participation of all states.

The discussion of whether the two degree target is the right one, and whether it is still feasible, should not distract attention from the real problem: the world must act. It is easy to agree targets for which no politician or CEO will ever be held responsible. But these targets are worthless if there is a lack of willingness to take the steps required to meet them. We have a long, and in part uncertain, road ahead of us: we must now agree our starting point – not where we will end it.

An abridged version of this article will appear in the Tagesanzeiger.

Further information

[1] Nature Geoscience Perspective: external page A scientific critique of the two-degree climate change target (Reto Knutti, Joeri Rogelj, Jan Sedláček & Erich M. Fischer)