A dream of foam

ETH researchers have discovered a new method to design stable foams. Their findings could make beer froth and ice cream last longer – and revolutionise construction materials such as concrete.

Oktoberfest is an exciting cultural event, but it is also a source of inspiration for materials scientists and engineers. Not the beer itself, but rather the beer foam is a source of inspiration.

A good head of foam – generally measuring about 1.5 cm and containing an impressive 1,500,000 bubbles – is supposed to be a sign of quality and freshness. Ideally, this foamy head remains stable, but several processes act to destabilise the bubbles: for example, liquid drainage of the foam, merging bubbles, or popping all can cause rapid destabilization. These are generic problems common to all types of foam, whether in food and drink or technologically advanced materials.

Undesirable change in the texture

One destabilisation process, in which large bubbles become larger and smaller ones shrink and eventually disappear, is particularly difficult to stop. Experts call this process “Ostwald ripening”, named for German chemist and 1909 Nobel Prize winner Wilhelm Ostwald, who first described this phenomenon over 100 years ago.

Ostwald ripening causes an undesirable change in the texture of beer foam and foamed food products, and it weakens product performance in many other situations as well. Achieving foam and emulsion stability thus presents a challenge across a wide range of materials science applications, from personal care products to advanced functional materials. “Foams – whether beer foam, ice cream or foam for insulation – tend to coarsen due to their bubbles merging or ripening,” explains Jan Vermant, Professor for Soft Materials at ETH Zurich.

Surface-active components, such as certain proteins in beer foams, can typically prevent or at least slow down ripening by lowering surface tension, at least in the short term. But these components cannot ensure the long-term stability of the foams, as they only slow down the ripening process, but cannot stop it once it has begun.

Vermant and his group have now taken a new approach to this foam stability problem and recently published it in the journal PNAS.

“For the first time, we have succeeded in quantitatively controlling the dissolution arrest of foam bubbles and formulating novel, yet universally valid strategies. These will help the food and materials industries to develop controlled and more effective stabilisers in order to prevent or stop Ostwald ripening,” says Vermant.

Network of particles stabilises bubbles

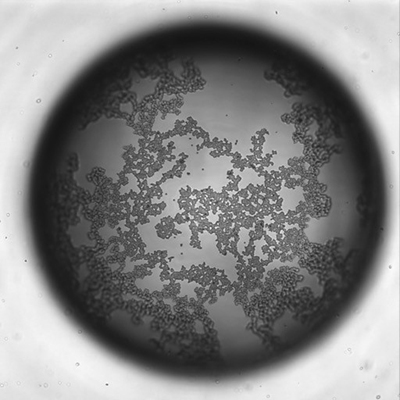

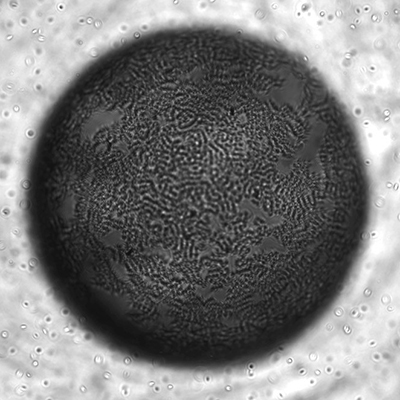

In their study, the ETH materials researchers showed how particular particles act as a stabiliser and protect small bubbles against shrinkage. For testing purposes, the scientists used micrometre-sized latex particles and particles shaped like rice grains. These particles were chosen to form an irregular network structure at the bubble interface.

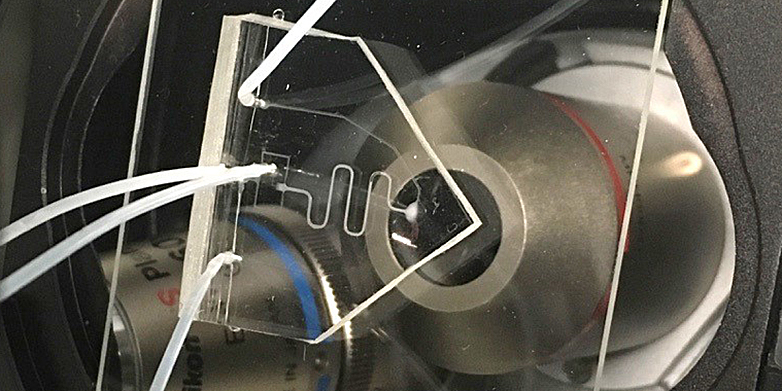

The researchers tested whether this network sufficiently supports the bubbles in a special microfluidic arrangement. They were able to coat individual bubbles with a controlled amount of the particle stabiliser and then expose them gradually to changing pressure conditions in a mini pressure chamber, thus simulating Ostwald ripening.

“This allowed us to determine precisely the pressure at which the bubble begins to shrink and finally collapses,” says Peter Beltramo, a postdoc in Vermant’s group. This particular experimental design allowed them to vary the number and nature of particles coating the bubble. Thus, they could relate the number of particles to the surface rheological properties. A surface yield stress was identified as the prime parameter that needs to be controlled.

They found that even partially covered bubbles can be as stable as those completely covered with particles. As a result, the required quantity of stabiliser can be predicted accurately. “Our findings will save a lot of materials and thus reduce costs,” emphasises Beltramo. Furthermore, the researchers found that a coated bubble can withstand a much higher pressure than an uncoated one.

Universally valid

The findings about the role of interfacial mechanics are universally valid for all materials with large surfaces or for applications in which surfaces play an important role, says Vermant. For example, the ideas and measurement techniques developed are applied to other cases of thin film stability, for example in biomedical applications such the films lining the alveoli in the lungs or the tear films on the eyes. “These films are very stable, with the stability being imparted by similar mechanisms – developed by nature,” says Vermant.

Although the findings are general, they are also of specific benefit to the food industry. The scientists can now search for edible stabilisers to make foamy foods, such as ice cream or even bread dough, last longer. “We provide the food industry and other companies with development guidelines and quantification tools that they can use to develop new products,” says Vermant. And indeed ice cream helped to initiate this research, which was co-financed by Nestlé. Yet, what is good for beer foam or ice cream may also be good to make concrete better. Incorporating small, stable bubbles makes it resist thaw-freeze cycles better and makes it lighter. Or: how thinking about beer can guide the design of new materials. Cheers!

Reference

Beltramo PJ, Gupta M, Alickea A, Liascukiene I, Gunes DZ, Baroud CN, Vermant J. Arresting dissolution by interfacial rheology design. PNAS, 11 September 2017. doi: external page 10.1073/pnas.1705181114