Narrating the Anthropocene

Recently, paired events – a lecture by geographer Kathryn Yusoff and a colorful evening “slam” – took place, organized by the fledgling interdisciplinary group, Environmental Humanities Switzerland. Both explored the potential and limits of the “Anthropocene” thesis: the idea that we’ve entered a new geologic epoch wherein humans are actively altering Earth systems.

While still unknown to some, the term “Anthropocene” has sparked a veritable explosion of discussion in and across corners of the sciences, humanities, and arts over the last few years — not unlike a (climate-change exacerbated) wildfire sweeping through a disheveled and volatile landscape. It is “an immense, omnivorous idea” according to the environmental historian and postcolonial theorist Rob Nixon, one that is currently sucking its adopters and detractors alike, “in their interdisciplinary masses,” into “its cavernous maw.” [1]

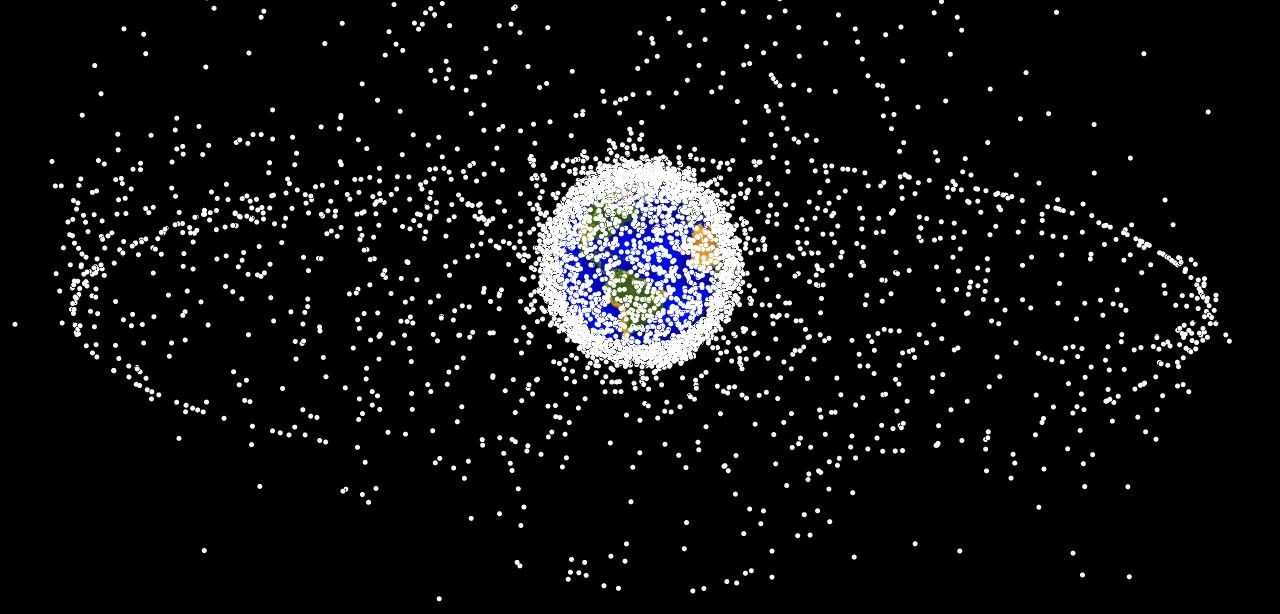

Introduced to the public debate by the atmospheric chemist Paul J. Crutzen and biologist Eugene F. Stoermer in 2000, the basic assertion is that we’ve entered an unprecedented epoch, one in which humans are altering Earth systems at the planetary scale, and moreover in ways that are being inscribed in the geologic record. [2] People have reshaped the land and its “resources” for millennia, but this has intensified markedly in the 20th century through activities including widespread deforestation, urbanization, dam construction, over-farming/-fishing, and increasingly drastic measures for extracting minerals, oil, and gas. Many scientists believe that our impacts are now penetrating broad, global systems (e.g., jet streams, atmospheric and oceanic chemistry) and deep geological layers (e.g., anthropogenic earthquakes caused by hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as “fracking”). This represents a categorical difference from the past — what we might call a thoroughly “post-natural” condition.

Origin Stories

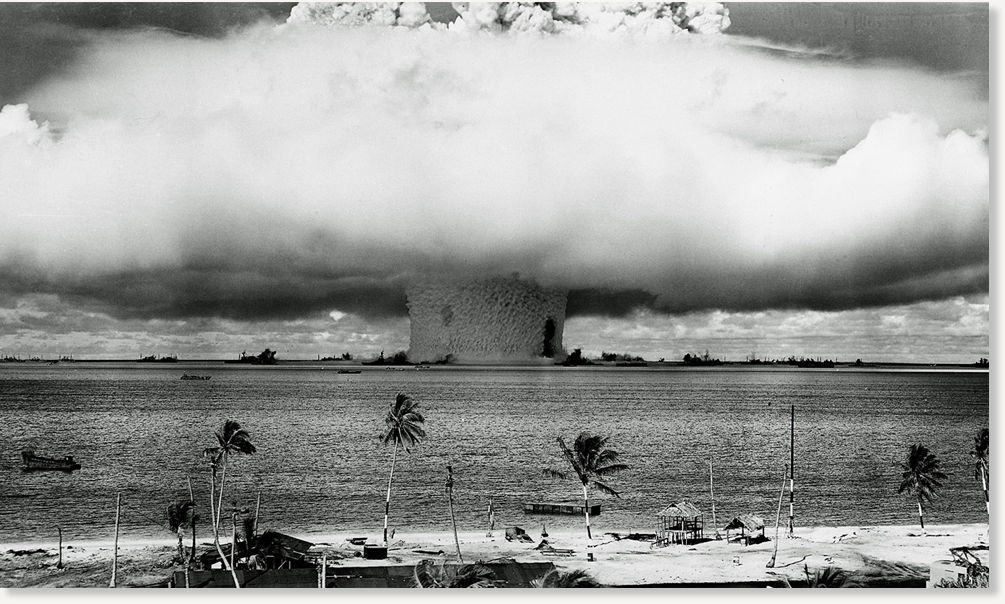

Fierce debate has ensued about the origin of this purported new age, with competing proposals (e.g., the collision of Old and New Worlds in 1492, the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, the first atomic blast in 1945) rendering very different stories about who we are as humans (anthropos) and how we relate to other species, to the material world, to vast time scales, and so on. [3] Indeed, we might think of the Anthropocene as a narrative device, asking what perspectives it opens or, conversely, forecloses. The most trenchant resistance to the concept has come from those who pinpoint its universalizing tendency to lump humanity into one, cohesive entity and thereby to obscure the specific causes of planetary-scale environmental crisis as well as its starkly uneven distribution. The human ecologist Andreas Malm succinctly argued earlier this year that “humanity is… far too slender an abstraction to carry the burden of culpability.” [4] Already, the feminist historian of science, Donna Haraway, had declared “Capitalocene” a more accurate, and politically useful, descriptor. [5]

Out of this maelstrom emerged twinned events on May 13, 2015, at ETH and the University of Zurich, both organized by Environmental Humanities Switzerland, a fledgling, interdisciplinary group made up of mostly Zurich-based historians, geographers, ecologists, philosophers, and artists. [6]

Who is this “Man” at the Center?

In her keynote talk, “Geopower: Genealogy After Life,” the radically inventive and renowned geographer Kathryn Yusoff (Queen Mary University of London) proposed that the focus on beginnings (and potential endings) in many Anthropocene conversations has been excessive, drawing attention away from another line of crucial questions. Who, for instance, is this “man” at the core of the Anthropocene, itself a “new life story of the human”? How is “he” related to previous constructions of the human, especially since the Enlightenment? How is human life constituted by and through geologic life? How might we move from thinking in terms of bio-politics (a term borrowed from the philosopher Michel Foucault) to geo- (as in geological, Earth-based) politics? Like Malm, Haraway, and others, Yusoff is keen to unsettle the invocation of a collective figure of humanity (and the colonial legacies associated with it), and instead to forge more fractured and stratified notions of human subjectivity, with issues of power always close in mind.

Anthropocene Slam: Meeting an Uncertain Environmental Future Halfway

If Yusoff’s lecture was highly theoretical, the “Anthropocene Slam” that followed was downright playful, even festival-like. [7] The host, artist Juanita Schläpfer-Miller, served red and green beverages in vials from a laboratory along with coasters representing different soil types as personalities [8]; the evening ended with a mock debate — with geographer Philippe Forêt as prosecutor and the audience as jury — about whether or not the Earth should be held accountable for failing to provide limitless resources without acting up, of late. In the Call for Participation, “slammers” had been invited to engage “fundamental questions about the future of our society in a time of limits to growth, climate change and over-exploitation of ecosystems” by way of short inputs, and the selection of an object to bring/contribute to a fictitious “survival kit for an uncertain environmental future.”

From Plastiglomerates to Anthropocenic Glasses

With the big-picture-thinking plant ecologist Christoph Kueffer as our charismatic moderator for the evening, we witnessed scientists from ETH and the University of Zurich and a broad range of disciplines as they responded to this experimental charge. A number took up the theme of fossilization, or material traces across deep time (the historian Marcus Hall on caprolites, or petrified feces, the artist Jeremy Bolen and myself on plastiglomerates, a new type of hybrid “rock” comprised of ocean-deposited plastic trash and natural sediments, fused via informal bonfires). Some were expressly pessimistic about our current, post-natural state of affairs (the physicist Michael Dittmar on the immanence of peak(ed)-oil, the environmental scientist Andreas Fischlin on climate change as a threat to not only human, but also humane, existence). Others, meanwhile, struck an optimistic note, though in some cases with full-blown irony. Beni Rohrbach, a PhD student in geography, advertised a pair of blinking, heart-shaped eyeglasses through which increasingly common environmental disasters (e.g. rising sea levels, oil spills) suddenly appear to pose delightful recreational and touristic opportunities. Agroecologist Angelika Hilbeck bespoke the wonders of synthetic biology as a “rescue for the environmental post-collapse,” with each and every one of what seemed to be her own words — we learned at the end — having been drawn directly from industry promotional literature. Conservation biologist Dennis Hansen encouraged us to follow the path of ancient tortoises in order to reimagine ecosystems in slow, back-to-the-future fashion.

Extra-Scientific Imaginings of the Present-Future

It was refreshing to see this group of primarily highly specialized (and accomplished) scientists wrangle with an “out of the box” format for public presentation, one that called less for expertise than for imaginative, speculative, and/or poetic approaches to some of the most pressing circumstances of our day. Indeed, it seems increasingly clearer that there is much at stake — potential worlds to be shaped or dashed — in the stories we build about the present, future, and future perfect (what will have been).

Further information

[1] Rob Nixon, “The Anthropocene: The Promise and Pitfalls of an Epochal Idea,” Edge Effects (6 November 2014): external page here.

[2] Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, “The Anthropocene,” Global Change Newsletter 41 (May 2000): 17-18. Within the International Commission on Stratigraphy there is an appointed Anthropocene Working Group which is expected to decide in 2016 whether or not the term be officially adopted.

[3] On the timing of the Anthropocene, see: Jan Zalasiewicz et al., “When did the Anthropocene Begin?” Quaternary International (2015); Simon L. Lewis and Mark A. Maslin, “Defining the Anthropocene,” Nature 519 (11 March 2015): 171–180; Clive Hamilton’s response to Lewis & Maslin: “Getting the Anthropocene So Wrong,” The Anthropocene Review (1 May 2015); and Adrian Lahoud, “Nomos and Cosmos,” e-flux journal 56th Venice Biennial (30 May 2015): external page Link.

[4] Andreas Malm, “The Anthropocene Myth,” Jacobin (30 March 2015): https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/03/anthropocene-capitalism-climate-change/. See also: “III. Against the Anthropocene” and four related entries by T.J. Demos on the Winterthur Fotomusuem (May-June 2015): external page Link.

[5] Donna Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble,” keynote lecture at Anthropocene: Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet conference, UC Santa Cruz (9 May 2014): external page vimeo.

[6] Environmental Humanities Switzerland external page website

[7] Our own event was inspired by another, “The Anthropocene Slam: a Cabinet of Curiosities,” organized by the Center for Culture, History, and Environment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (8-10 November 2014): external page Link. See also Libby Robin and Cameron Muir’s discussion of that conference in “Slamming the Anthropocene: Performing climate change in museums,” reCollections: A Journal of Museums and Collections 10/1 (April 2015): external page Link.

[8] Designed by soil scientist, Anett Hofmann (D-USYS, ETH Zurich, and Department of Geography, UZH) for the UN International external page Year of Soils 2015. More information on the corresponding project "Bruno Braunerde und die Bodentypen": external page here.

Comments

No comments yet