The Montreal Protocol at 30: what has it achieved?

When the Montreal Protocol was signed in 1987, no one knew the impact it would have. Today it is clear: the ban on substances that deplete the ozone layer has prevented hundreds of thousands of instances of skin cancer while effectively helping to preserve the climate. Yet the protocol also faces some unfounded criticism.

Yes, the hole in the ozone layer is still there, and we won’t be dispensing with the sunscreen any time soon. Nevertheless, we consider the environmental accord signed in Montreal, which will celebrate its 30th anniversary on 16 September 2017, as a scientific and political success story for the international community. But why?

The “Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer” [1] is a legally binding treaty enshrined in environmental law. All 197 members of the United Nations have ratified the protocol, committing to reducing and ultimately eliminating chemicals containing chlorine or bromine that deplete the ozone in the stratosphere, which is essential to preserving life on earth. Efforts initially focussed on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), followed later by bromine-containing substances and CFC substitutes.

Fewer tumours, lower temperature

Thanks to the consensus achieved in Montreal, estimates suggest that more than three million cases of skin cancer have been avoided over the past 30 years, including up to 300,000 cases involving highly malignant forms [2]. While the initial focus of the treaty was on health and ecological concerns, the full scale of the climate protection benefits began to emerge ten years ago (see this blog post about both aspects of the protocol [in German]). Between 1987 and 2017, the CFC ban prevented greenhouse gas emissions of some 200 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. In 2017 alone, the emissions saved will amount to roughly 13 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, or approximately one third of this year’s anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions [3]. In the period up to 2017, the emissions prevented by the protocol have precluded an additional global temperature rise of roughly 0.3 degrees Celsius.

The “hole” in the success

It is in the nature of the thing that the successes set forth here are based upon a comparison of the current state of our climate system with the situation as it would have been if we did not have the Montreal Protocol – “the world we avoided”, as it were [4]. This situation can naturally only be examined with the aid of computers. So are these accomplishments, in the end, actually real?

In late June 2017, pointing to the alleged unprovability of the claims and what it called a desire to create a “mythology of saving the world”, the Swiss weekly Weltwoche [5] scoffed at the notion that the fight against the depletion of the ozone layer should be considered the embodiment of successful international action against a global threat when the ozone hole still exists.

Ozone regeneration takes time

Regarding this suggestive statement we would like to clarify that, ever since the work by Molina and Rowland in 1974 [6], the scientific consensus has at no point been that the hole in the ozone layer would be closed 30 years after Montreal. On the contrary, the scientific debate was in fact unstintingly focussed on the disconcertingly long-term persistence of human-emitted CFCs.

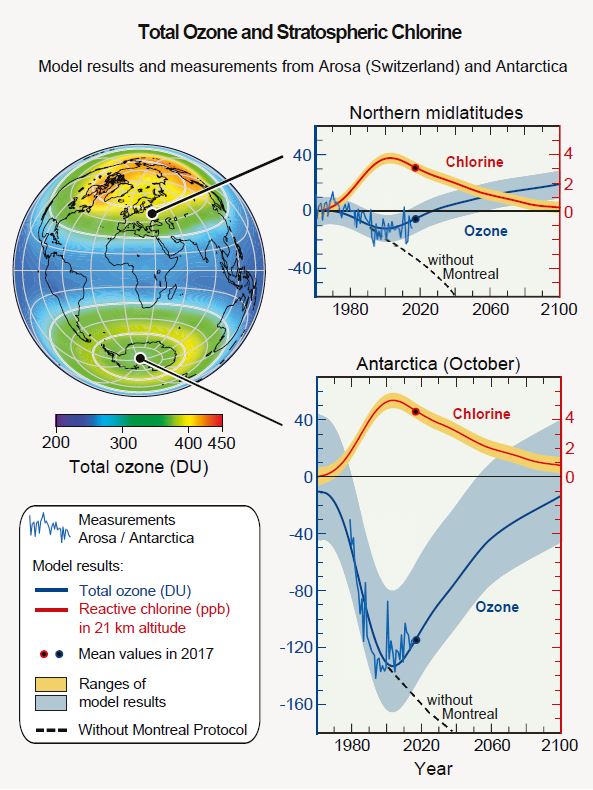

Modelling and measured data underscore the point: ozone measurements in Antarctica (fluctuating curve; see image) lie within the range predicted by the models. Only by around the year 2050 can we expect that CFCs in the atmosphere will have decreased to the extent that the “hole” will once again manifest the same amount of ozone as when it was discovered in the 1980s.

Depletion has stopped ...

The hole in the ozone layer will be with us for some time to come. So what are we celebrating on 16 September, the International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer?

Thirty years of the Montreal Protocol have ensured that the Antarctic ozone columns are no longer plummeting into the oblivion of the “world we avoided” (along the dashed black line “without Montreal” [6]). The protocol has created the conditions whereby the ozone hole can once again close up over the coming 30 years. The situation is similar in the northern middle latitudes, right above our heads: the five-percent drop in the ozone level demonstrated by the world’s longest-running measurement series in Arosa has evidently been stopped.

... but “saving the world” still an open question

Of course, this doesn’t mean that all is well, let alone that we have fully grasped all of the processes set in motion by humans. There are always uncertainties in scientific research – the concentration of ozone, for example, also depends on meteorological factors and naturally fluctuates within a wide range. This makes it difficult to demonstrate the effectiveness of measures. Montreal also has some very clear deficiencies. For example, the protocol paradoxically encouraged the production of substitutes for the banned CFCs, known as HFCs, which, although they do not deplete the ozone layer, are potent greenhouse gases (see this blog poston HFCs [in German]). Conversely, climate change also increasingly impacts the regeneration of the ozone layer because the ozone-destroying chemical reactions are themselves temperature-dependent.

The past three decades, however, have yielded one indisputable conclusion: the crux of ozone and climate questions is that we quite simply cannot analyse and resolve such complex, global environmental issues with simple desktop experiments, no matter how much the many critics may wish it to be the case.

Tom Peter composed this post together with Johannes Stähelin.

Further information

[1] The external page Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, Ozone Secretariat.

[2] Numerische Werte extrapoliert von Slaper, H., G.J.M. Velders, J.S. Daniel, F.R. deGruijl, J.C. van der Leun: Estimates of ozone depletion and skin cancer incidence to examine the Vienna Convention achievements, Nature, 384, 256-258, 1996.

[3] Velders, G. J. M., Andersen, S. O., Daniel, J. S., Fahey, D. W., and McFarland, M.: The importance of the Montreal Protocol in protecting climate, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104(12), 4814–4819, 10.1073/pnas.0610328104, 2007.

[4] Newman, P.A., et al.: What would have happened to the ozone layer if chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) had not been regulated?, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2113–2128, 2009.

[5] Reichmuth, A.: Aufstieg und Fall des Ozonlochs, Weltwoche, Nr. 26.17, 28. Juni 2017.

[6] Molina, M. J. and Rowland, F. S.: Stratospheric sink for chlorofluoromethanes: Chlorine atom catalyzed destruction of ozone, Nature, 249, 810–812, doi:10.1038/249810a0, 1974.

[7] Hegglin et al., Twenty Questions and Answers, About the Ozone Layer: 2014 Update, Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2014, WMO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

Comments

No comments yet