What does an image truly convey?

Philosophy of science in medical research: pharmacy students are learning how theory, methods and experiments affect scientific results and how to assess the significance of the results.

What happens in people’s brains when they lie? It’s Friday afternoon at the Fünffinger Dock on the Hönggerberg campus and 18 pharmaceutical sciences students are discussing the explanatory power and limitations of various scientific terms and methods. Three of them, Sara Dylgieri, Severin Lustenberger and Frederik Peißert, bring up a case study in which researchers study the regions of the brain that are activated when a person lies. The scientists found that the frontal and lateral regions of the brains are activated when a person lies, and that other regions of the brain are activated when a person invents a lie rather than when they express it.

The students’ discussion, of course, is less about the result and more about how it came about. The procedure is typical of scientific research, they conclude. The researchers worked with theoretical assumptions, or hypotheses, which they tested experimentally. They compared their results with the findings from existing research literature and then came to the best explanation currently available.

The students have a lively discussion about the assumptions underlying functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), an imaging technology that colourises activated brain regions with high spatial resolution in a digital image. In fact, the fMRI measures oxygen and blood flow in the vessels; thus, any link to a specific activity within the brain is indirect.

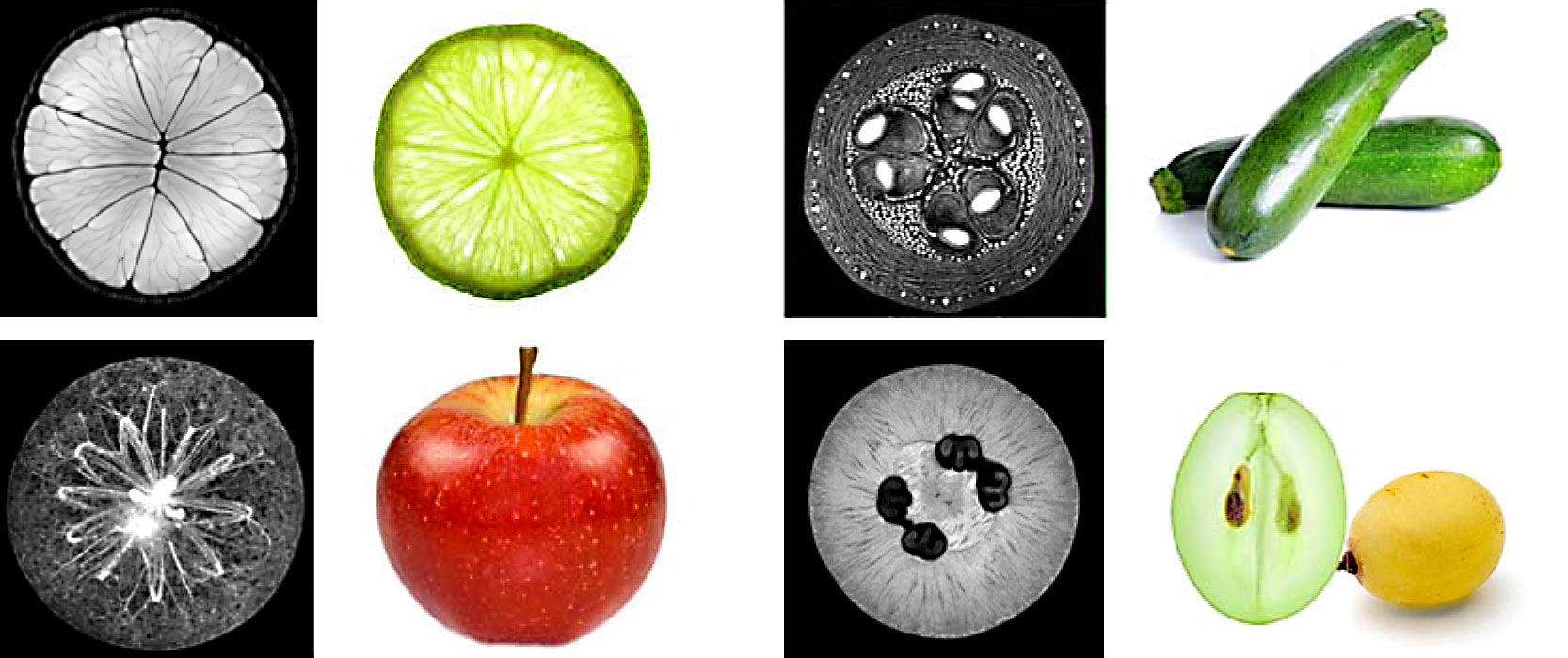

Drawing the right conclusions from images requires methodical knowledge about what exactly is being measured and how an image is created. Imaging involves multiple “translation steps” that are not always unambiguous: biological properties are rendered as physical quantities, converted mathematically into spatial coordinates and then assembled into a digital image.

No method reveals everything

The pharmacy students have acquired the skills necessary to evaluate the assumptions, justifications and implications of a scientific approach in the Scientific Concepts and Methods course. Over a week, they learn how the choice of a particular theory or method influences scientific work, and what to look for when evaluating the basic assumptions and concepts in their own projects.

“Anyone working on a current research problem should be able to justify the particular theories, approaches and experiments they use. Selecting the right ones requires knowing the strengths and limitations of each,” says Vivianne Otto, a lecturer at the ETH Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (IPW). She designed the course together with Elvan Kut, who is also a lecturer at the IPW.

The course is part of the completely restructured Master’s in Pharmaceutical Sciences that was offered for the first time in autumn 2017. The course prepares students for scientific work in basic research and industry (in contrast to the Master’s Pharmacy programme, which prepares students to work as pharmacists).

In addition to the chemical, physical and biological basis required to research and develop new drugs, the programme also provides reflective and practical skills, such as philosophy of science, ethics, academic writing, biostatistics and project management.

Discussing the results

Science also requires that researchers scrutinise the validity and soundness of their findings, and that they put their findings up for discussion. Accordingly, the course has been integrated into ETH Zurich’s Critical Thinking Initiative.

“Today’s pharmaceutical research uses and combines highly advanced techniques and computational methods. This requires a great deal of knowledge and an even greater degree of reflection in order to select the most useful approaches and to interpret the results,” says Kut. “That’s why we teach the philosophy of science directly in the context of current scientific methods,” explains Norman Sieroka, philosophy lecturer and Director of the Turing Centre Zurich, and the course’s third lecturer. “For this purpose, every course day we invite an expert to discuss with students the background, possibilities and limitations of cutting-edge research methods.”

Testing theories or charting new territory

Theory and experiment play a key role on the path towards recognised scientific knowledge. “Often, experiments are used to learn more about theories,” says Sieroka. Researchers make certain assumptions or hypotheses within the framework of a theory, and then make if-then postulations. They test these in experiments to see whether the data supports or weakens the theoretical assumptions.

“In addition to studying theories, experiments are also used to investigate uncharted territory and new phenomena,” Sieroka continued. These exploratory experiments are used to find regularities, infer if-then relationships and define new terms. Experiments also take place with no prior theory, such as when intelligent algorithms are used to filter out regularities from large datasets.

The students are interested and intrigued by this distinction and apply it to pharmaceutical research: in computer-aided drug research, says one, theory testing plays an important role. The basic assumptions are simulated on a computer and then tested in the experiment. In fact, the molecules do not always behave as they did in the computer simulation.

Responding to unexpected events in a cognisant way is the learning objective, says Otto: “Not all strange results are due to measurement errors. Rather, it sometimes forces you to modify or discard your initial theoretical assumption.”

From the course "Scientific Terms and Methods"

Comments

No comments yet