Combatting antimicrobial resistance

Thomas Van Boeckel is a Branco Weiss Fellow. His postdoctoral research at the Institute of Integrative Biology at ETH Zurich focuses on the overuse of antibiotics in animal husbandry in different parts of the world and potential measures to reduce their consumption.

One might expect to meet someone researching antibiotic resistance in a barn, wearing rubber boots and protective clothing, and perhaps carrying a test tube for collecting samples. But Thomas Van Boeckel does not work in the field: his research space is the computer on the desk in front of him, in a rather austere and almost makeshift office in the Institute of Integrative Biology at ETH Zurich.

The 33-year-old epidemiologist successfully applied for a external page Branco Weiss Fellowship, and is one of six Fellows appointed in July/August 2018. He was awarded a scholarship of 500,000 Swiss francs to fund research on antimicrobial resistance in livestock farming and potential measures to combat the misuse of antibiotics. “My work is different than just basic research: it extends into the political sphere and the impacts on society as a whole – which is precisely what the Branco Weiss Fellowship is interested in.”

Silver bullet loses its shine

Antibiotics still play a vital role as a silver bullet against bacterial infections. But since they are being used inappropriately or excessively, bacteria are increasingly developing antimicrobial resistance (AMR). There is a danger of bacterial infections in animals and humans running out of control – and some of them have already become virtually untreatable. Very few new antibiotics are brought to the market each year.

“My main motivation for researching this topic is that the bulk of antibiotics produced worldwide are not used to treat infections in patients, but are fed to animals raised for food, such as pigs and chickens,” Van Boeckel explains. Farmers use the drugs to treat infections in their livestock or – far more problematic – to promote growth and thereby speed up meat production. “This helps to reduce the amount farmers have to spend on animal feed,” the scientist adds, with a note of concern.

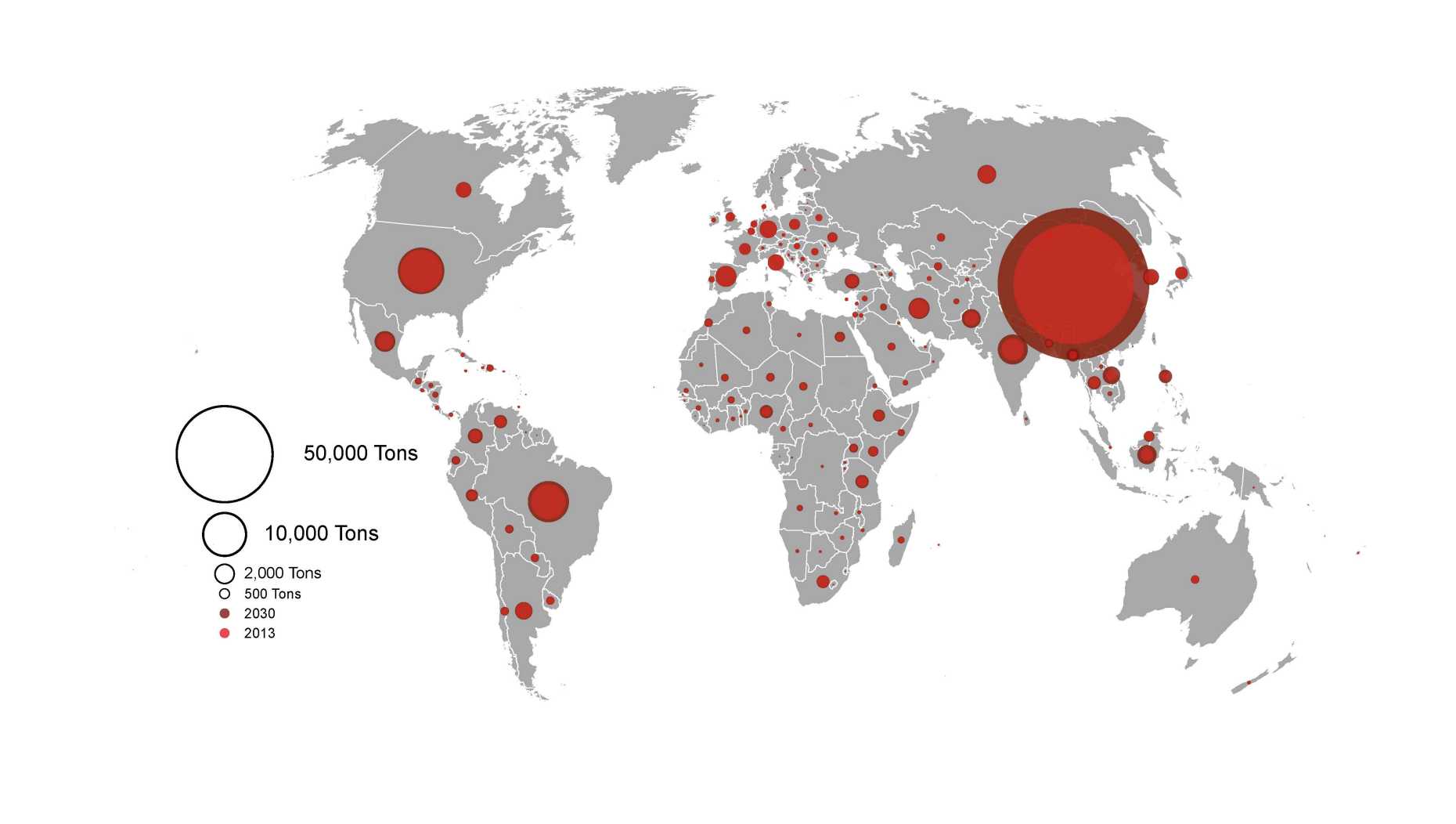

Demand for meat, poultry and eggs is growing rapidly across the globe – especially in emerging economies, where more and more people can now afford to buy meat. This is a good news to improve nutritional status of many around the world. But this has also triggered a massive increase in antibiotic use to ensure that meat producers are able to satisfy demand. China especially has caught up with this trend and is now the world’s biggest consumer of antibiotics.

“This inevitably puts more pressure on the bacteria,” Van Boeckel explains, “who respond by developing antimicrobial resistance – the greater the use of antibiotics, the faster the bacteria’s response.” This also increases the risk of humans being exposed to drug-resistant bacteria, whether through direct contact with the animals or through food they eat.

Producing a global map

The first project Van Boeckel has planned for his Branco Weiss Fellowship is to produce a global map of antimicrobial resistance. This is to give us a better idea of the scale of the problem.

But Van Boeckel will not be visiting farms and livestock breeders to collect his own data: instead he will be using data collected by hundreds of local researchers and vets who visit individual farms in their respective countries to bring together information on antimicrobial resistance. With the help of models, he will assemble these data into a global map with a resolution of 10x10 kilometres to identify the hotspots of antimicrobial resistance.

“It’s important to be able to gain an overview of the problem and bundle together the information in a way that is easy to communicate to political and economic decision-makers. It also helps us to pinpoint where resistance is starting to build up,” says the researcher. Local authorities may also be interested in this information to make targeted interventions where needed.

Examining the effectiveness of interventions

The other aspect being studied for this project is the use of intervention policies. Van Boeckel is investigating which potential interventions would be most effective in reducing antimicrobial consumption. He is thinking of consultancy and aid programmes in regions where antibiotics are being used as surrogates for good hygiene conditions in animal husbandry. One area the researcher is particularly interested in is how the imposition of a tax on non-human antibiotics could help reduce consumption.

In a study published a few months ago in the journal Science, Van Boeckel already proposed the idea of a global user fee of 50% of the current price of veterinary microbials. Funding from the Branco Weiss Fellowship gives him the opportunity to work out the details of this proposal.

It is easier to introduce alternatives to antibiotics in some countries more than others. “The crucial point is how much farmers rely on antibiotics as an integral part of meat production.” Keeping a few cows high up on an alpine meadow in Switzerland is completely different from intensive cattle farming with several hundred animals housed in the same barn. “I am also investigating such aspects in much greater depth,” Van Boeckel explains.

Politicians keen to hear what he has to say

It’s not just scientists who are interested in Van Boeckel’s findings: he has already been invited to speak to the EU and UK parliaments. He also tries to exchange ideas with industry leaders whenever an opportunity arises. “As a scientist, life is much easier if you keep a fairly low profile. However, we can only solve the problem of antimicrobial resistance if we share our knowledge with politicians and business leaders,” Thomas Van Boeckel says.

The Belgian scientist has been working at ETH for three years, but only came here by chance. Before that he was a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton, but was uncertainty his visa would be renewed to extend his stay. Therefore, he asked his boss where he could potentially move next (outside the USA) and was advised to apply at a University in London or at ETH Zurich. “Because I like climbing, I submitted my first application to ETH and Professor Sebastian Bonhoeffer gave me a job. Amazing!”

Avian flu in Thailand

Van Boeckel originally comes from Brussels and his native tongue is French, even though his surname is Flemish. He’s always been attracted to science. “I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t fascinated by science,” he says. “In fact, I was so bad at writing and music that I always knew I had to become a scientist,” he jokes.

But his path to becoming a researcher on antimicrobial resistance straightforward. “I started studying biology, even though I found theoretical physics more appealing – and failed my first year at uni.” He toyed with studying physics, but then decided to opt for biotechnology at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, partly because it offered better job prospects.

But the world of business did not appeal to Van Boeckel, who preferred the academic life. After graduating he completed a PhD in avian flu epidemiology. “My parents worked in public hospitals, so I was aware of health issues from a very early age. When it came to decide on a doctoral thesis, it was clear to me that it should be on something to do with medicine, rather than pursuing a biotech path”.

Tough life as a researcher

Having successfully completed his doctorate, he went on to postdoctoral studies in Princeton and now at ETH. Thomas Van Boeckel still thinks his future lies in academia: “I want to keep working in this sector.” But he’s also aware that academic careers can sometimes come to an abrupt halt, especially for academics of his age, who have to work really hard to stay at the top. Competition is rapidly increasing, particularly with the arrival of many talented students from India and China. And academic jobs can also impact on one’s private life: it’s not unusual couples to have jobs in different cities or even different countries. Flexibility is required – a considerable amount, in fact. That can be very tiring. “The past few years sometimes been very tough for me.”

He’s keen to stay at ETH Zurich, not simply because it is a nice town, but because he has learned to appreciate its many advantages. One of them is how compact the city is: the tram from his office to the airport only takes 20 minutes, and the train journey from his home to the mountains, where he can indulge his passion for climbing, is only one hour. “Where else in the world is that on offer?” he asks.

Reference

Van Boeckel T, et al. Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals. Science 29 Sep 2017: Vol. 357, Issue 6358, pp. 1350-1352. DOI: external page 10.1126/science.aao1495

Comments

No comments yet