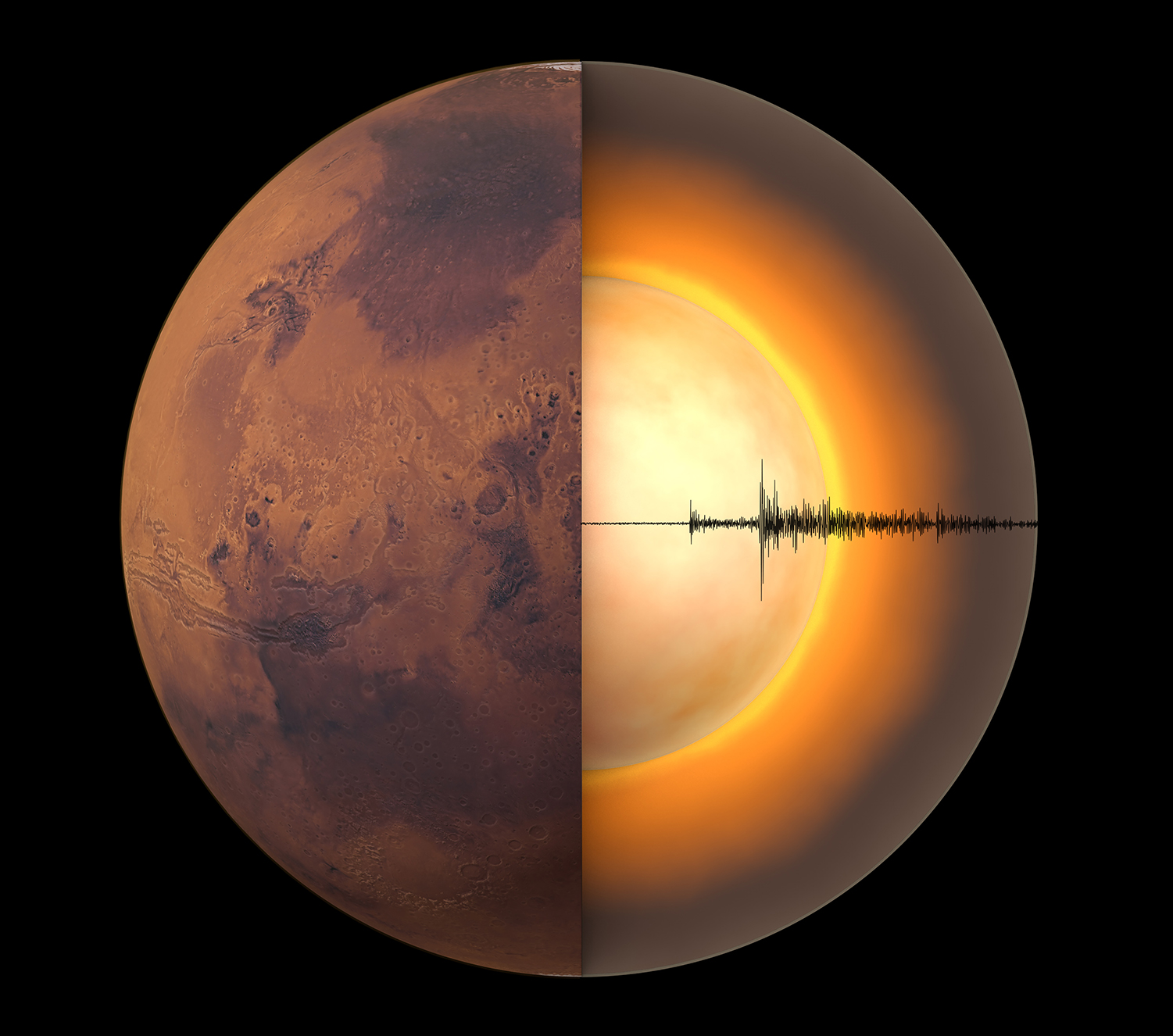

The anatomy of a planet

Researchers at ETH Zurich working together with an international team have been able to use seismic data to look inside Mars for the first time. They measured the crust, mantle and core and narrowed down their composition. The three resulting articles are being published together as a cover story in the journal Science.

Since early 2019, researchers have been recording and analysing marsquakes as part of the InSight mission. This relies on a seismometer whose data acquisition and control electronics were developed at ETH Zurich. Using this data, the researchers have now measured the red planet’s crust, mantle and core – data that will help determine the formation and evolution of Mars and, by extension, the entire solar system.

Mars once completely molten

We know that Earth is made up of shells: a thin crust of light, solid rock surrounds a thick mantle of heavy, viscous rock, which in turn envelopes a core consisting mainly of iron and nickel. Terrestrial planets, including Mars, have been assumed to have a similar structure. “Now seismic data has confirmed that Mars presumably was once completely molten before dividing into the crust, mantle and core we see today, but that these are different from Earth’s,” says Amir Khan, a scientist at the Institute of Geophysics at ETH Zurich and at the Physics Institute at the University of Zurich. Together with his ETH colleague Simon Stähler, he analysed data from NASA’s InSight mission, in which ETH Zurich is participating under the leadership of Professor Domenico Giardini.

No plate tectonics on Mars

The researchers have discovered that the Martian crust under the probe’s landing site near the Martian equator is between 15 and 47 kilometres thick. Such a thin crust must contain a relatively high proportion of radioactive elements, which calls into question previous models of the chemical composition of the entire crust.

Beneath the crust comes the mantle with the lithosphere of more solid rock reaching 400–600 kilometres down – twice as deep as on Earth. This could be because there is now only one continental plate on Mars, in contrast to Earth with its seven large mobile plates. “The thick lithosphere fits well with the model of Mars as a ‘one-plate planet’,” Khan concludes.

The measurements also show that the Martian mantle is mineralogically similar to Earth’s upper mantle. “In that sense, the Martian mantle is a simpler version of Earth’s mantle.” But the seismology also reveals differences in chemical composition. The Martian mantle, for example, contains more iron than Earth’s. However, theories as to the complexity of the layering of the Martian mantle also depend on the size of the underlying core – and here, too, the researchers have come to new conclusions.

The core is liquid and larger than expected

The Martian core has a radius of about 1,840 kilometres, making it a good 200 kilometres larger than had been assumed 15 years ago, when the InSight mission was planned. The researchers were now able to recalculate the size of the core using seismic waves. “Having determined the radius of the core, we can now calculate its density,” Stähler says.

“If the core radius is large, the density of the core must be relatively low,” he explains: “That means the core must contain a large proportion of lighter elements in addition to iron and nickel.” These include sulphur, oxygen, carbon and hydrogen, and make up an unexpectedly large proportion. The researchers conclude that the composition of the entire planet is not yet fully understood. Nonetheless, the current investigations confirm that the core is liquid – as suspected – even if Mars no longer has a magnetic field.

Reaching the goal with different waveforms

The researchers obtained the new results by analysing various seismic waves generated by marsquakes. “We could already see different waves in the InSight data, so we knew how far away from the lander these quake epicentres were on Mars,” Giardini says. To be able to say something about a planet’s inner structure calls for quake waves that are reflected at or below the surface or at the core. Now, for the first time, researchers have succeeded in observing and analysing such waves on Mars.

“The InSight mission was a unique opportunity to capture this data,” Giardini says. The data stream will end in a year when the lander’s solar cells are no longer able to produce enough power. “But we’re far from finished analysing all the data – Mars still presents us with many mysteries, most notably whether it formed at the same time and from the same material as our Earth.” It is especially important to understand how the internal dynamics of Mars led it to lose its active magnetic field and all surface water. “This will give us an idea of whether and how these processes might be occurring on our planet,” Giardini explains. “That’s our reason why we are on Mars, to study its anatomy.”

References

Khan A et al.: Upper mantle structure of Mars from InSight seismic data. Science, 373, (6553) p. 434-438. doi: external page 10.1126/science.abf2966

Stähler S et al.: Seismic detection of the Martian core. Science, 373, (6553) p. 443-448. doi: external page 10.1126/science.abi7730

Knapmeyer-Endrun B et al.: Thickness and structure of the Martian crust from InSight seismic data. Science, 373, (6553) p. 438-443. doi: external page 10.1126/science.abf8966

InSight mission

InSight (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) is an unmanned external page NASA external page Mars mission. In November 2018, the stationary external page lander, which is equipped with a external page seismometer and a external page heat probe, safely landed on the Martian surface. The geophysical instruments on the red planet permit exploration of its interior. A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (external page SEIS) instrument to NASA, with the principal investigator at IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris). Significant contributions for SEIS came from IPGP; the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany; Imperial College London and Oxford University in the United Kingdom; and Jet Propulsion Laboratory (USA).

Comments

No comments yet