Does greater mobility mean more and more traffic?

The rapid transport of people and goods is both a growing demand as well as an economic necessity. The price we pay for it is an ever-increasing volume of traffic. When it comes to tackling this dilemma in the future, it’s worth taking a look at the past.

There is a saying in German: a mistake is not the end of the world, as long as you don’t repeat it. Of course, what exactly constitutes a mistake is often a question of interpretation – especially in transport planning, which has seen years of ideological and emotionally driven debate about how to tackle the steadily rising volumes of traffic. In my thesis, I examine the development of the transport network and travel in Europe from the Middle Ages to the present day. And with some of the issues currently preoccupying politicians, citizens and the media, I get an inevitable sense of déjà vu. So, let’s have a look at the history of mobility.

Distance as humanity’s early enemy

In The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, his seminal work of 1966 [1], French historian Fernand Braudel describes the geographically restricted lives of ordinary people in the late Middle Ages. Everyday life took place in situ and within walking distance. Travel was a rare, dangerous and laborious task – and anything but pleasurable. Transport infrastructure was poor, limited to former Roman roads, trade routes and certain navigable sections of river. Communities were often isolated, and the potential for economic development was correspondingly meagre. Braudel identifies distance, not plagues or disease, as humankind’s number-one enemy.

Conquering distances through technical progress

At that time, most people lived in villages rather than towns, but science and technology were pushing ahead in the latter. For example, more accurate measuring technology led to better roads, and using the three-field system for crop cultivation led to greater yields of food and fodder for horses. The speed of travel increased. Almost as a side-effect of this, towns enjoyed rising prosperity, which in turn attracted more people. This resulted in a lively process of exchange (of food, labour and trades) between towns and their surrounding areas on the one hand, and between the different towns on the other. This served to benefit not only commerce but also communication, and the first postal companies began to transport people in addition to letters.

Tailbacks of carriages and the clatter of hooves

In the modern age, inter-town connections for journeys by horse, or even by carriage, were growing at a rapid pace. Many towns were completely overwhelmed by traffic, although travel remained the preserve of the privileged. Londoners complained of the constant clatter of horses’ hooves robbing them of their sleep and of dangerous conditions in the narrow city streets. The transport routes were therefore widened with a view to alleviating the situation. But the stream of horses and carriages – along with tonnes of manure – simply grew larger. There were times when elegant ladies didn’t dare leave their homes for weeks on end.

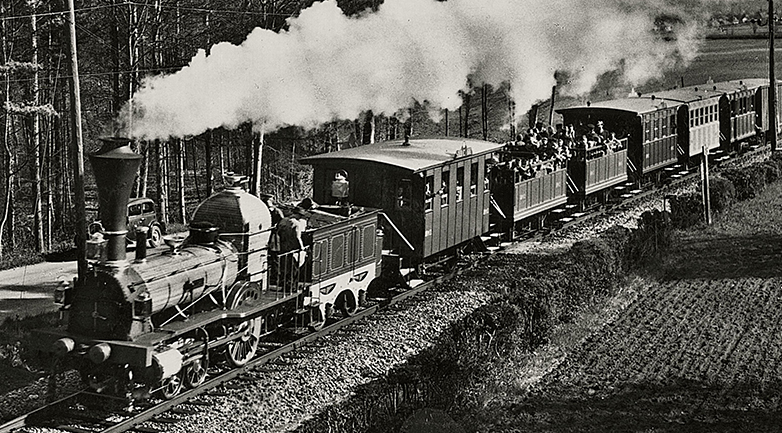

A side-effect of a newly mobilised world

The advent of the railways in the 19th century brought the first tangible improvements: they not only reduced journey times considerably but also brought travel within the reach of the masses. International goods and passenger transport became established. When Switzerland’s first train pulled into Basel from Alsace in 1844, the smoke, fire and noise are said to have brought people running on to the streets in a terrible panic. But this was also an important year for a different reason. In 1844, potato blight wrought havoc across North America. Just a few months later, in June 1845, the disease appeared in Europe for the first time in what is now Belgium. The spores are thought to have travelled across the Atlantic on a steamship, the railways’ water-borne counterpart. By early September, the whole of Western Europe was affected. This side-effect of a newly mobile world led millions of Europeans to die of starvation. (See [2] for a modern counterpart of potato blight.)

From railways to motorways

A little over 100 years later, Switzerland found itself in the grip of mass motorisation. Anyone who was anyone bought themselves a car, and Switzerland decided to connect the entire country with a network of motorways. The cantons implemented one bypass after another and Basel-Landschaft was no exception. The A2 opened in 1970, cutting right across the canton, and the Liestal bypass was completed just a few years later. German politician Hans-Jochen Vogel was quoted around this time as saying, “He who sows roads shall reap traffic” – a saying that is still widely used today. And, in his own way, Vogel was proved right: by the 1990s, the traffic on Liestal’s main street was backing up again, just as it had done in the 1960s – despite the bypass. [3]

Does supply create demand – or vice versa?

And today? Urbanisation, a global megatrend, marches onwards. In cities, the debate concerning correct transport policy rages on, although opinion is now divided by issues such as parking rather than horse manure and noise. The expansion of roads, both within urban areas and in the countryside, remains an effective tool that reliably attracts a majority of political support, even in Switzerland. What failed in 18th century London and 20th century Basel-Landschaft is now somehow supposed to work – at least, this is how investments worth billions are justified.

I recently came across an interesting article from North America [4] that offers a scientific confirmation of Vogel’s impression: more traffic infrastructure is no solution to traffic jams. This is clearly also true of the railways, which, with Rail 2000, have already become “a victim of their own success” – nevertheless, without them, Switzerland would probably stop working altogether. [5]

Will technology alone be enough?

The ever faster and ever more powerful transport system has undoubtedly brought prosperity and diversity to Switzerland. However – and this is part of what makes working with mobility and transport so exciting – it has also led to a multitude of unintended side-effects for society and the environment. And as has often been the case in the past 200 years, the transport sector now faces another process of rapid change: digital and autonomous mobility, where self-driving cars clean up the streets thanks to optimum utilisation of capacity.

Whether digitalisation and technical progress actually deliver the expected gains in efficiency – or whether they stimulate even greater demand – remains to be seen. [6] Regardless of the outcome, we should ask ourselves as a society what benefit additional transport actually brings.

In my view, it would be wise to ensure that transport and mobility are always considered in the context of society, business and the environment, and the cost and benefits analysed comprehensively. However, many effects experience a considerable time lag, and in reality they are part of ongoing cycles rather than the outcome of simple cause–effect relationships. The more intensively we base our lives on mobility, the more extensive and far-reaching the triggered upheaval will be – negative, yes, but thankfully also positive.

At present, I see no catch-all solution to this dilemma – but perhaps you do?

Further information

[1] Ferdinand Braudel: La Méditerranée et la Monde Méditerranéen à l'Epoque de Philippe II (external page UCpress)

[2] Planes are doing today what the railways did in the mid-19th century. This summer, many berry and stone fruit producers experienced very poor harvests that have been blamed largely on the spotted-wing drosophila. This vinegar fly originated in Asia and was likely introduced into Switzerland by air via the international fruit trade. These crop failures may not be leading to a hunger crisis, but they are causing considerable economic damage.

[3] History of Basel-Landschaft: external page Meher Strasse, mehr Verkehr

[4] The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: external page Evidence from US Cities

[5] Macroeconomic effects of public transport with a particular focus on densification and clustering effects: external page PDF (in german)

[6] For more information, read this opinion piece by Paul Schneeberger in the NZZ, 13 October 2016: external page Mobilität ist kein Selbstzweck

Comments

No comments yet