Number theory has no gender

Özlem Imamoglu has been fascinated by the hidden properties of numbers since she was a child. The ETH professor is also committed to helping more women pursue careers in mathematics.

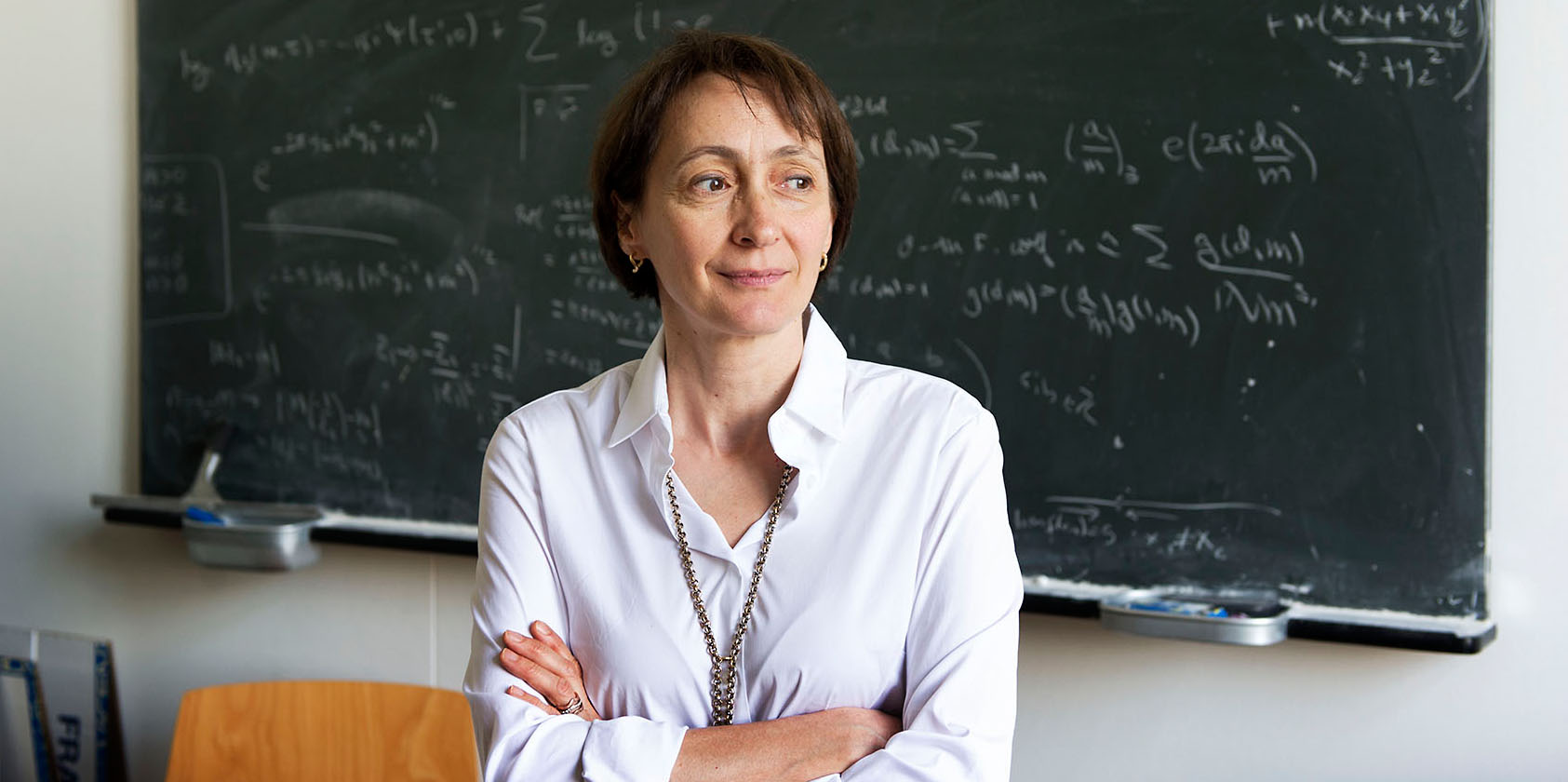

When you enter Özlem Imamoglu’s office in the main building at ETH, the first things you notice are the many personal items, pictures of family and friends, and souvenirs. The Professor in the Department of Mathematics conducts research in the field of number theory. A blackboard, every last inch covered in formulas, hangs above her desk. To the naive, uninitiated observer these symbols have little meaning at first glance – and yet they obviously seem to have a clear structure and reflect some sort of hidden order.

Imamoglu gazes at this “picture” on the wall and says, “I see mathematics as an art form, because I find the structures it describes to be incredibly beautiful.” Of course, the beauty of mathematics is not a sensory experience in the same way as music or painting, for example. It is only visual and tonal in certain ways.

Mathematics is much more the product of a simplified abstraction: “As a mathematician, I don’t study any one particular object, but rather the properties that various objects share with each other. I try to show and explain this in the simplest way possible,” says Imamoglu. In this respect, quantity with specific properties represents a mathematical structure.

Beauty in the science of structures

“Mathematics is primarily concerned with structures. It is not defined in terms of a specific object. This is what makes it different from many other disciplines,” adds Imamoglu. Oil flowing through a pipeline, she explains, can be described mathematically in the same way as blood flowing through a vein – as a movement through a cylindrical vessel.

She finds it beautiful and at the same time fascinating how, conversely, simply formulated mathematical theorems can be improved, expanded, and applied to complex problems. Imamoglu says that the structures of the numbers and figures she studies represent generalisations of relatively simple, periodic functions, for example. They have the mathematical property of repeating their function values, i.e. numbers, at regular intervals. This means that they can be used to describe sound waves, water waves, or electromagnetic waves. From there, Imamoglu also studies what are referred to as automorphic forms, which encode a great deal of interesting, number theoretic information.

The “courage to venture into the unknown”

Imamoglu herself was also pretty naive when she first discovered mathematics. Looking back on her time as a student, she says that she had the “courage to venture into the unknown” when she set off on her career. Her older brother helped spark her interest in mathematics back when she was still a child, but Turkish-born Imamoglu began her studies in electrical engineering at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara, as her parents were worried that studying mathematics would not offer her a secure career path. They would have preferred for their daughter to study medicine.

But Imamoglu did not give up and changed to mathematics just after completing her Bachelor’s degree. She then went on to earn her Master's and PhD at the University of California, Santa Cruz before, as is customary in the world of science, taking on various professorships: at universities in Santa Barbara, Istanbul, and at ETH Zurich. When she entered the field of mathematics, she was already familiar with fundamental tools of analytic number theory, such as differential equations, from her engineering studies, but she still lacked certain basic mathematical knowledge.

What makes the “myth of genius” so discouraging

She closed the gaps and today, looking back on her experience, she says: “To succeed in mathematics requires hard work, persistence, perseverance, and then more hard work.” What irritates her most about the “myth of genius” is its implication that only inherently gifted individuals can make it in the field of mathematics. “Even the most talented individuals don’t succeed in mathematics without hard work,” she explains. “The notion that a successful career in mathematics depends solely on natural talent is discouraging for women in particular, especially when you factor in the stereotype that women have an inferior capacity for maths.”

Imamoglu says that this stereotype has a lot to do with cultural norms: “The first time I heard that women were less able at mathematics was in the USA and Switzerland. It was different in Turkey back then.” At least in the educated circles in which she grew up. Imamoglu says that a woman’s decision to pursue a career in mathematics is influenced by preconceptions such as these, as well as the general economic conditions, the ratio of female to male professors, and the childcare services on offer.

Imamoglu also says that when women study mathematics, they must trust their own abilities and share their experiences with other women. In the coming days, she will be involved in the European Girls’ Mathematical Olympiad (EGMO) for 14 to 19-year-olds. “My aim is to motivate young women to study mathematics and show them that it is a viable career path.”

European Girls’ Mathematical Olympiad (EGMO)

The European Girls’ Mathematical Olympiad (EGMO) has been supporting the advancement of young, talented women in mathematics since 2012. This year the event will be held in Switzerland for the first time and hosted by the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich. ETH students will also be involved in the organisation. The EGMO will commence on 7 April at ETH Zurich with a welcome address by ETH Rector Sarah Springman. Teams from 43 countries, each comprising four secondary school students, will compete in two 4.5-hour exams that require logical thinking, creativity, mental stamina, and practice. The medal ceremony will take place on 11 April at the Irchel campus with speeches from UZH Rector Michael Hengartner and Head of the Zurich Department of Education Silvia Steiner.

external page European Girls’ Mathematical Olympiad (EGMO), 6 to 12 April 2017 in Zurich: Girl power and fun with mathematics!

Comments

No comments yet