Crooked to the millimetre

The technology pioneered by the ETH spin-off incon.ai allows blocks to be positioned with pinpoint accuracy, creating structures with aesthetic designs and augmented acoustics.

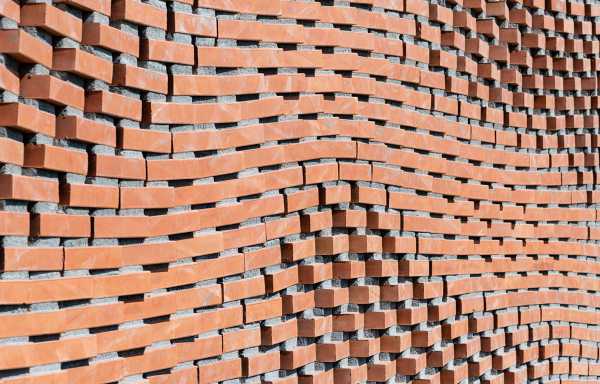

Shadow plays, wavelike patterns or acoustic effects: bricks can be placed at special angles to create aesthetic architectural designs. To create the required effects and at the same time ensure a stable structure, the individual bricks need to be positioned with millimetre accuracy. It would take an enormous effort to achieve such precision with conventional building plans and masonry techniques.

A new technology based on augmented reality (AR) makes it possible to realise even the most unorthodox ideas. Timothy Sandy, a specialist in robotics and an ETH Pioneer Fellow, is the scientist who developed the concept.

Masons guided by software

First the architects draft the design on the computer and load the 3-D plans into the software. While working on site, the masons direct a camera at the brickwork. The software recognises the objects and compares the position of the individual components with those in the virtual design.

A monitor shows the masons exactly how they need to place the individual bricks. "This innovative technology allows humans to build with almost the same accuracy as robotic systems," says Sandy. "This allows entirely new shapes and structures to be created." Sandy's software has already been used in two projects.

At the foot of Mount Olympus in Greece, ETH architects from Gramazio Kohler have built a wine cellar with a total facade of 225 m². A local company completed the construction in less than three months. "We were only on site for a week to prepare everything," Sandy explains.

The wine cellar's semi-transparent facade creates a light pattern that changes over the course of the day. The gaps between the individual bricks also ensure optimum lighting and ventilation for the building's interior.

Shadow patterns and noise protection

The second project involves the walls of the cafeteria of Basler & Hofmann in Esslingen near Zurich, a timber construction also designed by Gramazio Kohler Architects. The faces of the individual timber blocks are first cut into polygons. The asymmetric shape of the blocks creates customised shadow patterns on the wall.

In addition, the varying gaps between the blocks improve the acoustic absorption and function as air ducts for the ventilation system behind the walls. Three acoustic walls with a total area of 90 m² were constructed in this fashion.

Robotics combined with human craftmanship

The software developer Timothy Sandy, 33, has a background in robotics. After studying mechanical engineering in the US, he came to ETH Zurich to complete his masters in robotics before moving on to a doctorate in robotics-assisted construction. He is now making this expertise available to masons and carpenters. "To be honest, I prefer working with people than with robots," he jokes.

Above all, however, robots still cannot match humans when it comes to mobility and dexterity. Robotics-assisted construction is currently only possible with very specific, flat bricks. "The software makes it possible to combine the advantages of computer design and human craftsmanship".

In both pilot projects, the software was loaded onto a computer connected to a camera and a monitor. A simple smartphone functions as a terminal device.

"The new technology is much more accurate than other AR solutions," Sandy says. For example, it detects and tracks objects despite occluded views or background clutter. Even strong camera shake or a system restart are not a problem.

Sandy recently set up the spin-off "incon.ai" together with co-founders Fadri Furrer and Abel Gawel. As part of his ETH Pioneer Fellowship, Sandy is currently assessing how the technology could be positioned in the market and who would benefit from it.

The young founders also want to continue to refine the technology. Sandy says they want to make the software more precise, stable and above all user-friendly. The team is also working to accelerate the entire process, so that computer-assisted construction will eventually be just as quick as conventional methods.

Comments

No comments yet