"In two weeks ICU capacities could be at their limit"

ETH Professor Thomas Van Boeckel and his colleagues have developed a model that enables them to predict the occupancy of intensive care beds. At the moment, this does not bode well for the coming weeks, if the corona virus continues to spread unchecked.

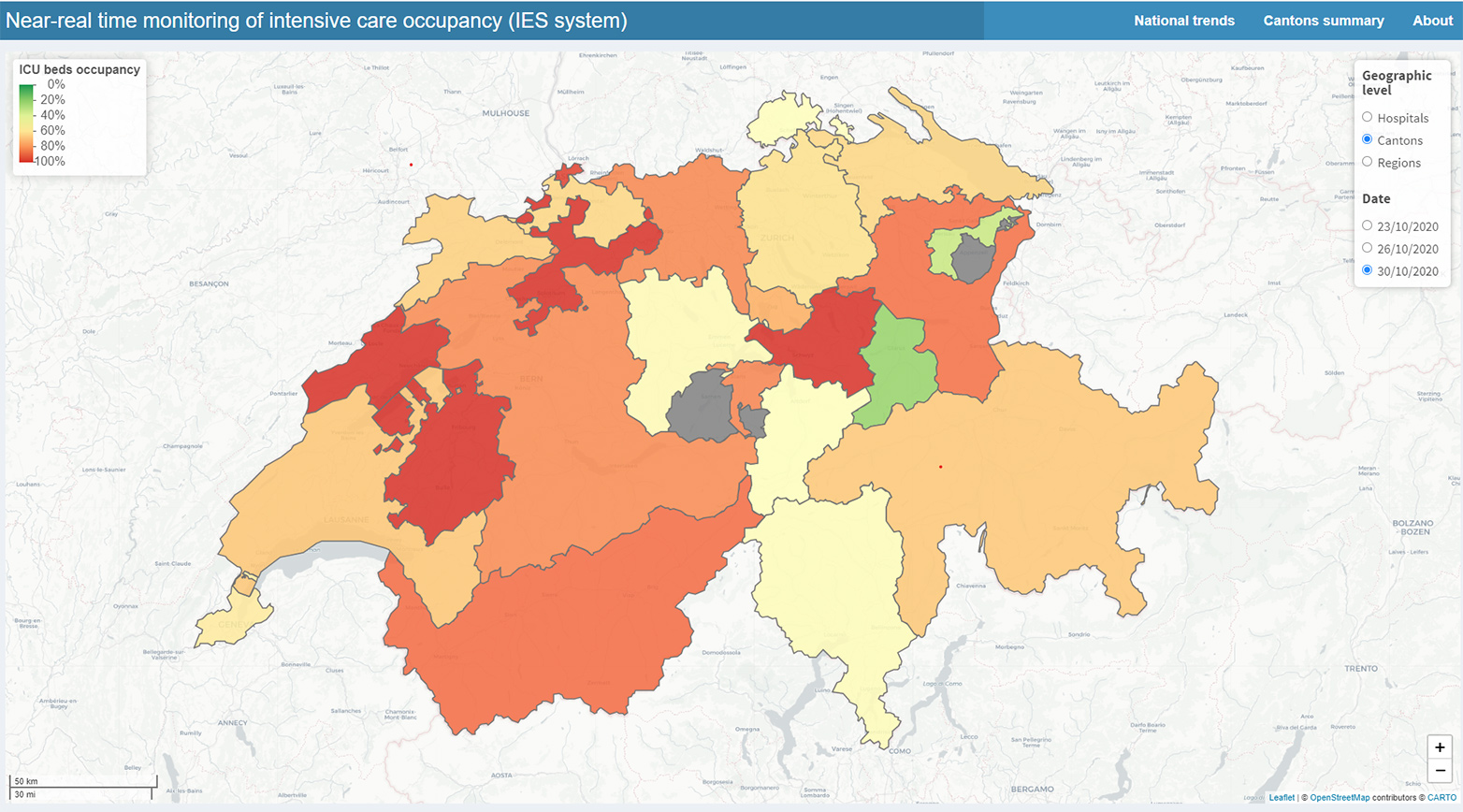

You have launched a website with forecasts of intensive care unit (ICU) occupancy in Swiss hospitals. It is attracting a lot of interest at the moment. What can one see on the webpage?

Our external page platform shows at a glance the occupancy level of beds in intensive care units, categorised by region, canton and individual hospital. However, only hospitals themselves and the Swiss army have access to the latter information. We also provide forecasts of how the situation might evolve 3 and 7 days ahead.

How accurate are the forecasts?

As with most epidemiological models, a forecast can be wrong, but it can also be useful. In the past week some of the epidemic models have struggled to capture the explosive trend of the epidemic. In mid-September the epidemic slowed down, and many epidemiologists were puzzled by that trend. But in October the pandemic has erupted again. Traditionally, epidemic models are not so good at capturing such highly variable situations.

How do you address this problem?

We work with three different models, each with different properties. The third model is called the MG model, and has been developed by colleagues from SwissTPH. It is better suited at capturing such very short-term variations. I would encourage people to look at the MG model in the coming days. It is the most accurate at the moment.

What data do you use?

We use data from several sources. Since March, we’ve been using data from the Coordinated Medical Services (CMS) of the Swiss army. That’s for the occupancy of the ICU beds, the total number of beds available and the number of people occupying these beds. We also use data from the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), such as number of cases and deaths. When the FOPH does not report, e.g. on weekends, we use data from openzh.ch, the Specialist Unit for Open Government Data for the Canton of Zurich. We also use data from University Hospital Zurich about the duration of stays of patients in the ICU.

Is there a problem with the consistency of the data?

Not really. The principal challenge has been gathering the data from different actors. Sometimes it goes very fast, because we have a simple verbal agreement with some of the data providers. Sometimes it has been trickier to break through administrative hurdles. Perhaps during an epidemic, traditional procedures for data sharing should be reconsidered or agreed in advance.

In spring the model was criticised because it said ICU capacity would be exhausted, even though hospitals had never hit the limit of their capacities. They had also taken on new beds, so overall capacity was larger than expected. Does the new model take into account these “hidden” capacities?

This has been the subject of much discussion. Part of the reason for that was divergence in the number of beds certified by the Swiss Society for Intensive Care Medicine, the number of beds inputted by hospitals in the IES system from KSD as ‘certified’, and the number of ad-hoc beds put into service during the first wave. The latter was not always reported in a timely fashion due to the emergency situation, so we didn’t have this information for our very first forecast.

Has this problem with “hidden beds” been solved now?

Yes, things have moved in the right direction, through collaboration with the Swiss army and the Swiss Society for Intensive Care Medicine. We have had many discussions, compared data sources and expert opinions and we now agree on what is a realistic limit for the ICU bed capacity in Switzerland (1,400). Hospitals have also definitely improved the reporting of timely information, which helps us help them. There are still hospitals that seem to get confused with reporting the right information in the right field of the CMS system, although these are now increasingly rare events.

So all in all, the model is more reliable and more accurate?

This week the situation has been very explosive, and we are currently adapting our model to better reflect this. As I said earlier, for the time being the ‘MG’ model from Swiss TPH is best at capturing the ongoing situation. But I think the quality of the data that we have to support the model has improved considerably over the last months. We also stand ready to add forecasts from other groups in Switzerland to our website.

The capacity of ICU beds is 65% at the moment. It’s not only Covid-19 patients, correct?

Absolutely, that’s important to say. At the moment, the majority of patients in ICUs are “normal” patients that had urgent surgery or an accident. The problem is that the number of Covid-19 patients is increasing very quickly, so ICU beds could be filled very rapidly. Working with my colleagues from the Task Force, we have estimated when that might happen.

And what is the answer?

On Friday, October 23rd, Professor Martin Ackermann presented our results at Point de Presse. The answer is that beds might be full in two to four weeks (from 22.10.2020). But that could change if stricter measures are taken.

Are we prepared for that?

That’s really a question for the medical staff and doctors. I think even if stricter measures are decided today, we have to look at the situation in two weeks, because new measures would take two weeks to have an effect. Our forecasts suggest that if nothing is done, on the current trajectory we will be dangerously close to the capacity of the Swiss health system in two weeks. But beyond looking at bed numbers, the limiting factor is the medical personnel to attend to patients in these beds. You can always buy new beds, but you can’t “buy” more medical staff. Doctors and nurses have already been under considerable pressure during the first wave of the epidemic. They are understandably tired. That is critical. When we talked to the Swiss Society for Intensive Care Medicine, they suggested that a reasonable capacity of beds doctors could attend to is 1,400 patients in ICU. Therefore, we should really not get close to that limit. That’s the message!

The chart shows that 1,600 ICU beds were available on 16th April. The peak occupancy back than was a little more than 1,000. Now you set the limit at 1,400 ICU beds?

There is a limit. Beyond 1,400 beds, doctors really think the quality of care cannot be guaranteed. That was a major factor in Switzerland’s success in dealing with the first Covid-19 wave. We didn’t have the situation seen in Italy or the UK where there was not enough personnel to take care of patients. So, we see 1,400 as the maximum number of ICU patients we can have in the hospitals.

Are we running into a situation like Bergamo?

That depends on what the population and the authorities do. If nothing is done, we could run into a situation like Bergamo. But I hope that wise counsel will prevail and we don’t get there. It is important to stress that every day counts in order to avoid a situation like that. Given the current rising trend of the epidemic, and assuming that we would have reached the 1,400 ICU capacity, with another 200 beds added, we would gain two days before ICUs are full again. Increasing the capacity is not the solution. We really need to halt the transmission of the virus.

With what measures?

We have to do the things we are already familiar with. The system that managed to keep the situation under control – test, track, isolate and quarantine – is increasingly dysfunctional because of the very high number of cases. So we need to reinforce this system, but also consider other options to reduce transmission.

What measures can the government now take across the whole of Switzerland?

That’s not for me to decide. I only look at the situation of Covid-19, and with my colleagues we provide evidence to policy makers, who ultimately make the decisions. The Science Task Force has made very clear recommendations (link in email): we need to work from home wherever possible, limit gatherings as much as we can, avoid all places with a high probability of transmission, such as places with poor ventilation and a lot of people in the same space, such as bars, sports places etc. These are very concrete measures to reduce the transmission of the virus. This also is what neighbouring countries have done to a large extent. Belgium, for example, has closed all bars for one month, while France is closing bars and restaurants after 9pm. We must understand that we need this type of measures to reduce transmission. Remember in March and April we imposed even stricter measures and it took some time to reduce transmission.

How should people prepare in hospitals? Do they rely on your model now?

I cannot speak for the doctors, they know best how to prepare. But we have had many requests from them this week for access to the hospital level data. The process has been quite positive. Some of them say the data is useful and accurate, some say that it wasn’t accurate – but then we collaborate with them, try to understand why, and try to adjust. We always strive to improve in response to their feedback.

Will the model be improved in the near future?

We’re working around the clock at the moment to do that. There are invisible heroes making vital contributions, including the group of students and postdocs who have been working with me since March. I would like to take this opportunity to thank people at ETH and other Swiss universities: Cheng Zhao, Nicolas Criscuolo, Peter Ashcroft of ETH, Burcu Tepekule of USZ, Monica Golumbeanu of SwissTPH, and Riccardo Delli Compagni who recently joined our team thanks to the support of SNF. Some of these students took time off from their own projects to keep working on icumonitoring.ch. The Vice President for Research has supported them financially, so we are very grateful for that too.

Do you also collaborate with ETH Professor Tanja Stadler and her group that is calculating the R value?

Yes, we work together in the Swiss Covid-19 task force, and we meet every Monday. Although this week it was more like every day! So we constantly discuss our models in depth. Furthermore, we are using information from her model to try and refine ours. The collaboration with her and her group has been very helpful in the further development of the website.

About

The 35-year-old Thomas Van Boeckel has been Assistant Professor of Health Geography and Policy at ETH Zurich since 2019. He is a member of the Swiss National Covid-19 Science Task Force of the Swiss Confederation, working in the expert group "external page Data and modelling", which is headed by ETH Professor Sebastian Bonhoeffer.

Comments

No comments yet