Shelter, stability and beauty

After 15 years as Professor of Architecture and Construction, Annette Spiro recently retired to become professor emerita. Her lectures and publications inspired a whole generation of architecture students at ETH Zurich.

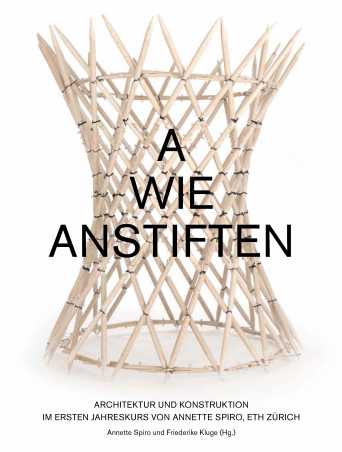

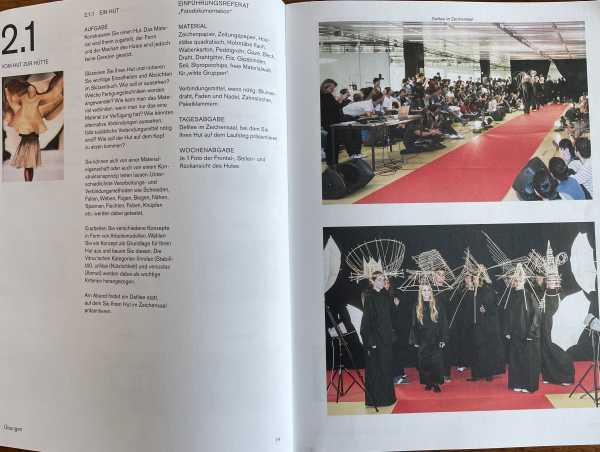

You might assume that hats have nothing to do with architecture – unless, that is, you have taken the first-year foundation course in architecture and construction run by ETH Professor Annette Spiro. Her students start by measuring their own head and making an attractive hat from the materials provided to them – and then they turn the hat into a hut! “Transforming a hat into a hut-like dwelling not only releases aspiring architects from the temptation to blindly follow architectural models and assumptions; it also introduces them to three of the most fundamental themes in architecture: shelter, stability and beauty,” says Spiro.

The ETH professor has spent over 15 years using these kinds of activities to make students more aware of the connections between material, structure and form. In doing so, she has successfully conveyed her passion for design to a whole new generation of architects. The pedagogical concepts she developed are now an integral part of the Department of Architecture’s introductory courses.

From Basel to Brazil

Born in Thusis in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in 1957, Spiro took a roundabout route to becoming an architect. During a three-year apprenticeship as a goldsmith and silversmith at what was then known as the School of Art and Design (HGKZ) in Zurich, she began helping her sister, who had already embarked on a course in architecture, to build models. She quickly discovered her own passion for the subject and, in 1982, decided to study architecture at ETH Zurich. Her enthusiasm for craftsmanship was something she would never lose sight of throughout her career.

After completing her studies, she worked for Guillermo Vazquez Consuegra in Seville and for Herzog & de Meuron in Basel. In 1990, she and her husband, Stephan Gantenbein, decided to give up their jobs and their apartment and emigrate to Brazil. However, they soon realised that Brazil in the early 1990s wasn’t an easy place for an architect. The country was in the grip of a major economic crisis, and the couple stayed only a year before moving back to Switzerland.

Yet this abrupt end to their dreams of emigration also marked a new beginning for Spiro: in 1991, she decided to set up her own firm with her husband as her business partner. Their breakthrough came with a project to extend and renovate the Hümpelihof farm in Füllinsdorf, for which they won the canton of Basel-Landschaft’s award for the best building project.

Paulo Mendes da Rocha provides inspiration

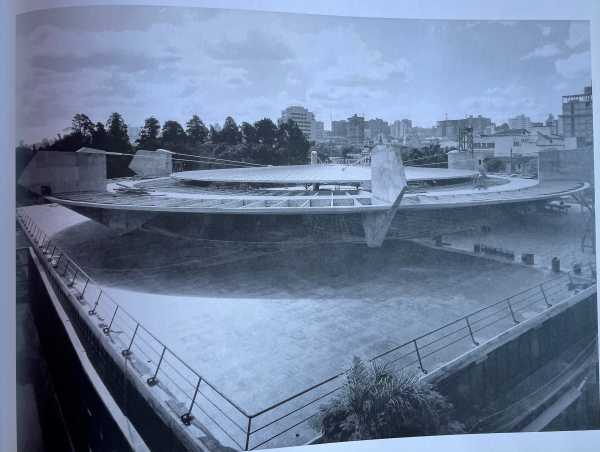

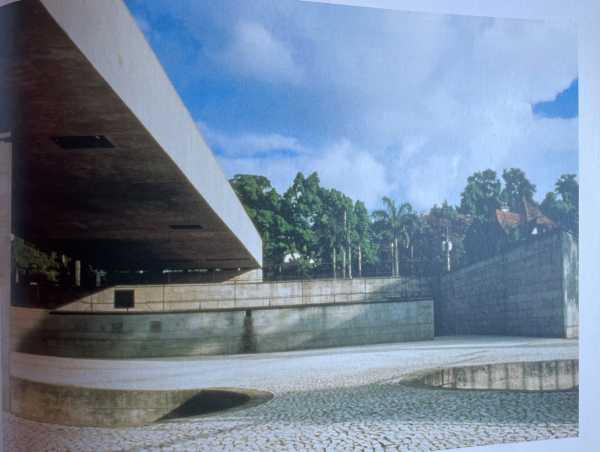

Even after returning to Switzerland, Spiro still had Brazil on her mind – or, more specifically, the architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha. Inspired by his work, she decided to write a book about him. She would eventually spend nine years working on her book about the future Brazilian Pritzker Prize winner, receiving countless rejections from publishers and using her own money to finance part of the cost of producing the book before it was finally published in 2002. “It took tremendous perseverance to see it through,” she recalls. Despite all the hurdles, the book was a huge success and played a significant part in establishing da Rocha’s reputation in Europe.

Even today, Spiro’s fascination with da Rocha continues to inspire her vision of a simple, direct form of architecture defined by the load-bearing structure. “The first time people set eyes on da Rocha’s long-span buildings made of raw concrete, they are simply lost for words,” she wrote in an obituary in the Swiss newspaper NZZ. “The spaces in his buildings are always defined by the load-bearing structure.”

An oasis in Oerlikon

Situated in the Zurich district of Oerlikon, the red-plastered block of 90 apartments stands like a fortress between the velodrome, the exhibition hall and the Hallenstadion arena. It’s an unpromising location for a residential building – and that makes it all the more surprising when you catch a glimpse of its inner courtyard, a green oasis framed by a warm and welcoming wooden façade. The contrast could hardly be greater.

“We designed a building that stands up to its harsh surroundings and creates a peaceful, gentle alternative world for its inhabitants,” says Spiro. She and her business partner and husband Stephan Gantenbein were awarded the building cooperative project in 2001. This was the second invited competition that Spiro’s firm had won, and it marked a key step in her career that would eventually pave the way to working at ETH Zurich six years later.

When asked whether the building reveals her signature architectural style, and to what extent it is representative of her work, Spiro finds it hard to give a definitive answer. “Every project forces us to engage anew with a place and to reinterpret the needs of our client and of the building’s inhabitants.”

Building plans are love letters

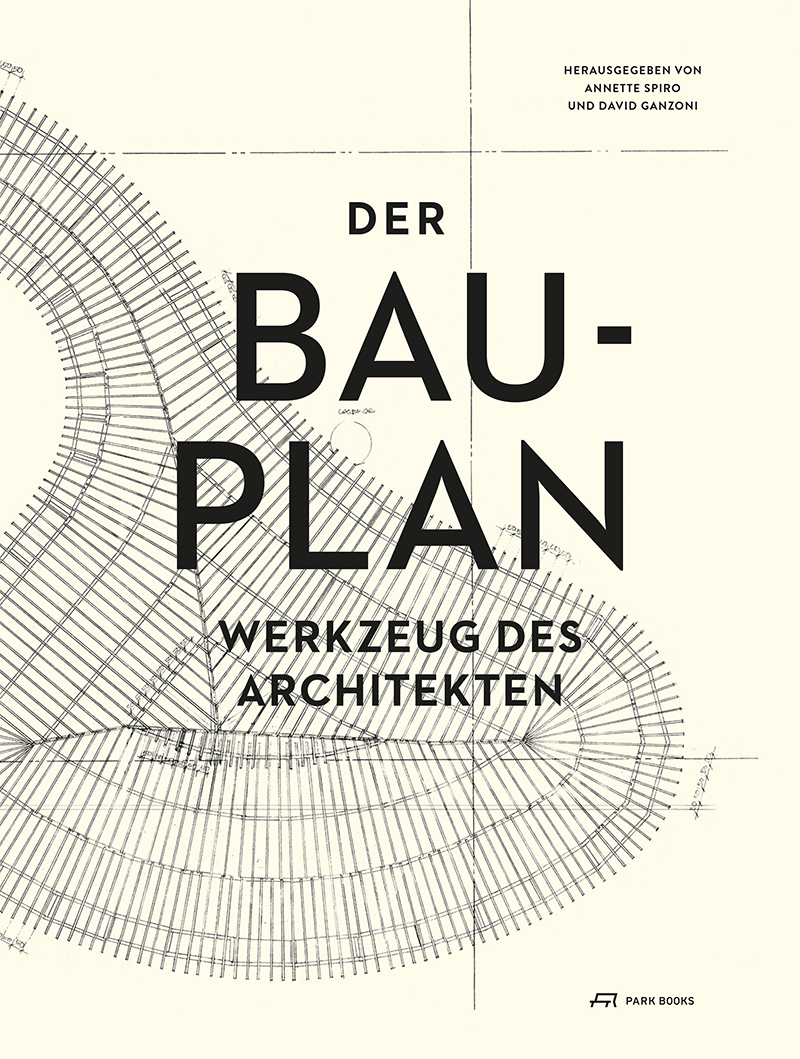

“Building plans are love letters” was the title of the lecture that Spiro gave in 2007 as part of her application for the Chair of Architecture and Construction at ETH Zurich. Her presentation broke with convention by including nothing but architectural drawings. “I wanted to show that building plans are more than just a technical tool. They are a unique form of expression that evoke an architect’s signature style. And my arguments seemed to convince the jury.”

She subsequently wrote commentaries on one hundred different architectural drawings and compiled them in a book entitled The Working Drawing, The Architect’s Tool, which Spiro published in 2013 and is still proud of today.

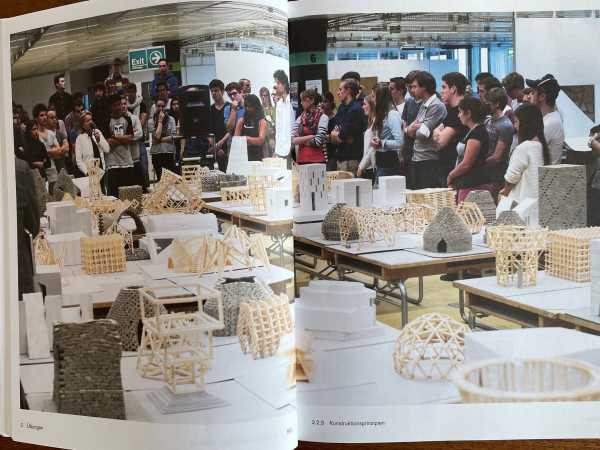

Having obtained her professorship at ETH, Spiro began to spend less time working at her firm and threw herself wholeheartedly into her teaching and research. Her department is renowned for its hands-on teaching approach and its in-depth exploration of building materials. In 2010, for example, it collaborated with the ETH Architecture and Civil Engineering Library to compile a collection of materials for architects; and in 2012, it introduced the Material Workshop elective course, which helps students get to grips with both the theoretical and practical aspects of building materials.

Investigating clay and plaster

Together with her teaching assistants, Spiro repeatedly addressed some of the more neglected aspects of the architecture industry. One of these was clay. Though it is one of the oldest building materials, clay has steadily been supplanted by concrete since the start of industrialisation. Drawing on the support of clay expert Martin Rauch, Spiro’s students used rammed-earth construction techniques to build a vaulted pavilion on ETH Zurich’s Hönggerberg campus. This was the first time a vault of this kind had been successfully constructed using prefabricated clay components.

Spiro showed that clay can still rise to the challenge of modern architecture, and she argues that it offers some very real advantages: “Rammed clay comes straight out of the ground, is fully biodegradable and is not baked, which saves energy. As a building material, it also creates a good indoor climate – plus it’s easy to repair and recycle.” Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the use of clay as a building material will increase in the future, in part because it requires expensive manual labour, but also because there are so few standards governing this type of construction.

As well as her interest in clay, Spiro is also fascinated by another material that is ubiquitous on building sites: plaster. “Even though we encounter this mixture of sand, lime and water just about everywhere, we realised that we actually know very little about it,” says Spiro. Her book About Plaster: Creating and Developing Surfaces, which appeared in 2012, reveals how the design possibilities of this material go far beyond what its standard applications might suggest. Her book has since become a standard reference work that can be found on the shelves of almost every architect’s firm.

Beginnings and endings

In 2018, Spiro published an account of the experience she had gained during her 15 years of teaching in a work entitled How to Begin? She discussed how to teach architecture and construction in a first-year course – and how to inspire a passion for design in aspiring architects.

The book offers a convincing case that, right from the start, architects should constantly be reflecting on the fundamentals of their discipline. “What holds a building together? How is the building used? What effects does the light have? What are the proportions of the rooms? And how does material influence form? These questions are just as relevant to first-year students as they are to experienced practitioners,” says Spiro.

Spiro will soon say farewell to ETH Zurich – but there’s no chance of her getting bored. As well as taking up the role of visiting professor at Cambridge University, she will also be embarking on a new book project on interior plastering. In her spare time, she also hopes to devote more time to drawing and to work on a graphic novel.

The secret chronicler

For ETH, Spiro’s departure means losing not only a dedicated lecturer but also a secret chronicler of her subject. Put simply, she knows more about young architects at ETH Zurich than almost anyone else. Since 2007, she has seen how her students’ perceptions of themselves have steadily evolved from one year to the next.

“Today’s architecture students no longer aspire to become overnight sensations by creating some kind of spectacular building. They’re much more interested in how architecture can help to create a fairer, more inclusive and more sustainable world,” says Spiro. “And I find that very encouraging.”

Comments

No comments yet