Waging a war for land and soil

The war in Ukraine is also a war for soil. Sebastian Dötterl, Professor for Soil Resources at ETH Zurich explains what makes Ukrainian soil so valuable and why it will become even more geopolitically significant.

Since February 2022, Russia’s war of aggression has brought suffering to the people of Ukraine. In that time, there have been a parade of insightful analyses that explain Russia’s imperialist interest in Ukraine. But I would like to address one aspect that I feel has so far received too little attention. Whatever other ideologies are at work, the war being fought in Ukraine is also about some of the 21st century’s key resources: farmland and mineral deposits.

“We’re talking about regions that are already incredibly valuable and will become yet more valuable – and Putin knows that.”Sebastian Dötterl

The soil of the continental temperate zone

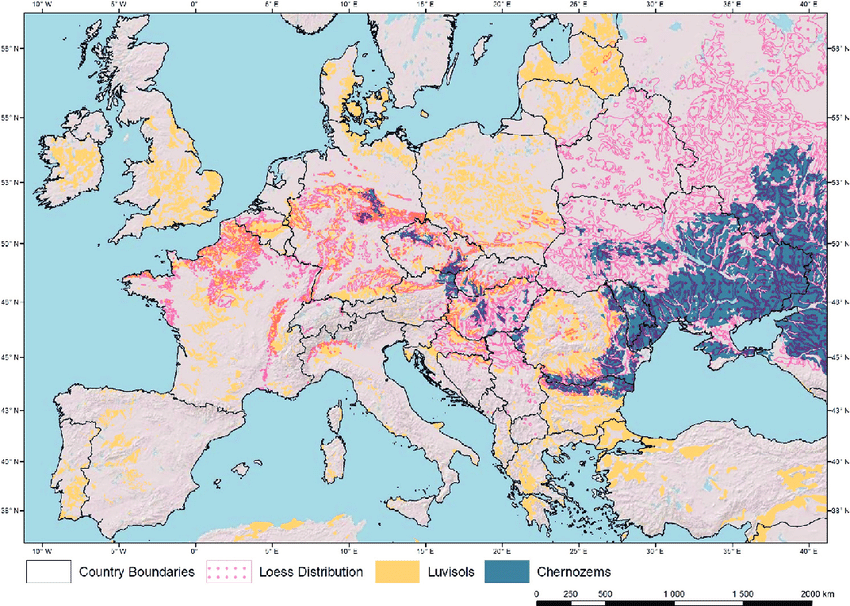

It’s no secret that Ukraine has a wealth of fertile farmland and that the southern and eastern parts of the country in particular are rich in rare earths, ores and other metals. But few people are aware of how these are distributed within the country and why: just as a country’s ore deposits depend on its geology, the fertility of Ukrainian soil is based on a uniquely thick humus layer and an extremely fertile material made up of what are known as loess deposits. This type of fertile soil, referred to as “dark earth” or “black earth” due to its colour, is found in other parts of the world, too. But nowhere else in Europe is it so widespread as in southern and eastern Ukraine and the neighbouring parts of Russia – in other words, precisely the regions Russia lays claim to.

By way of comparison, the thickness of the humus-rich layer typical of dark earth is often less than 20 cm. But in Ukrainian farmland, it is commonly at least 60 cm and can even be more than a metre thick. And that’s across an area roughly six times the size of Switzerland. We can actually see this valuable soil feature quite clearly whenever we look at pictures of Ukrainian Army trenches on the eastern front.

A buffer against the effects of climate change

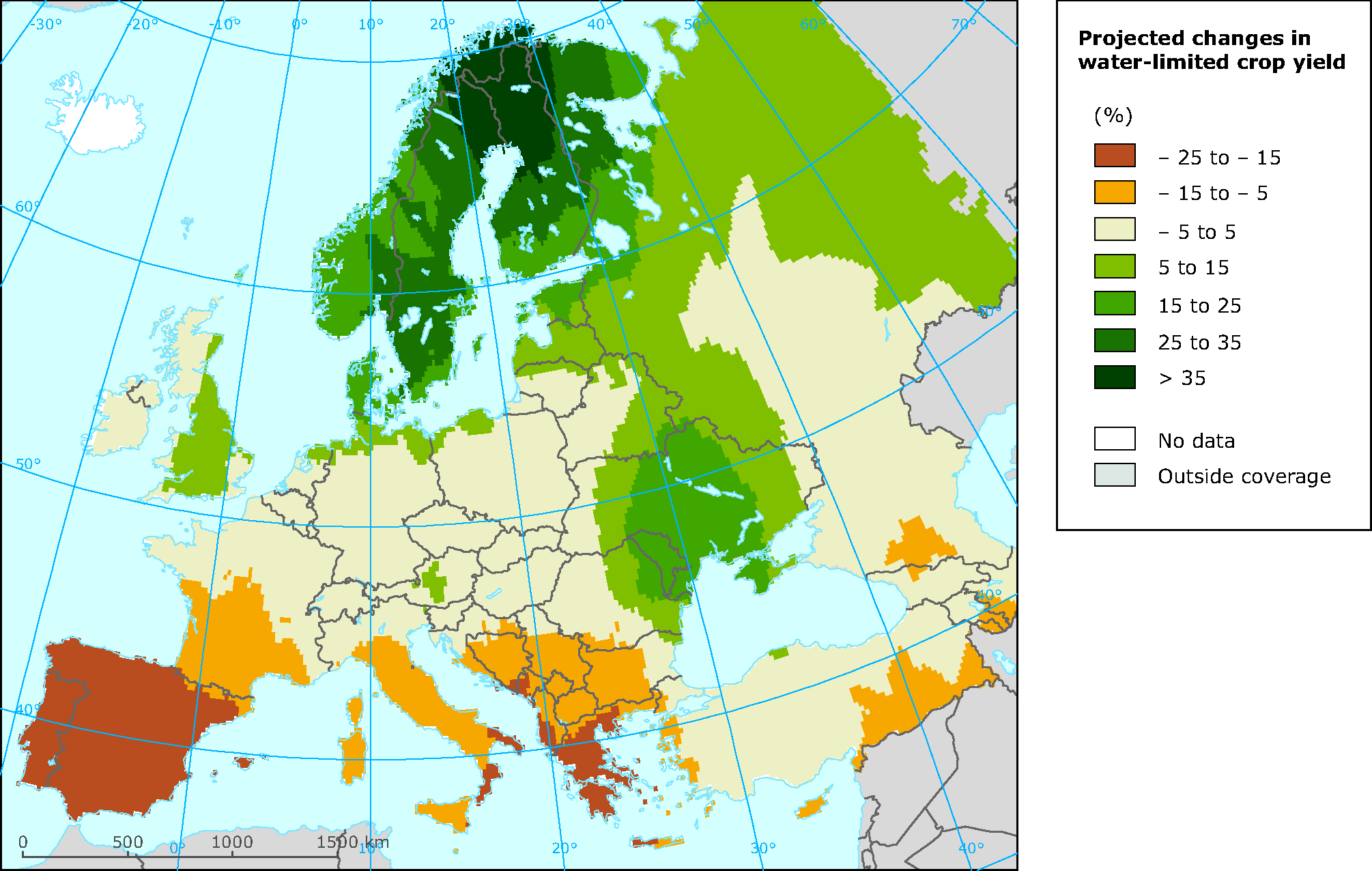

Ukrainian soil will become even more valuable in the future. In one way or another, virtually all forms of commercial farming lead to soil degradation, which in turn has a negative impact on soil fertility and yield. As a result, much of Europe’s soil is already heavily degraded and thus less resilient to disruptions such as climate change. Ukraine’s dark earth will be able to successfully offset this kind of damage and loss in yield for many decades to come.

Indeed, against the backdrop of climate change, this fact takes on a new relevance. Today’s most common climate scenarios suggest that these regions of Ukraine are likely to suffer far less from the negative effects of climate change than the countries of central and western Europe. With European farming set to endure increasing drought and extreme weather events, Ukrainian soil will become even more valuable.

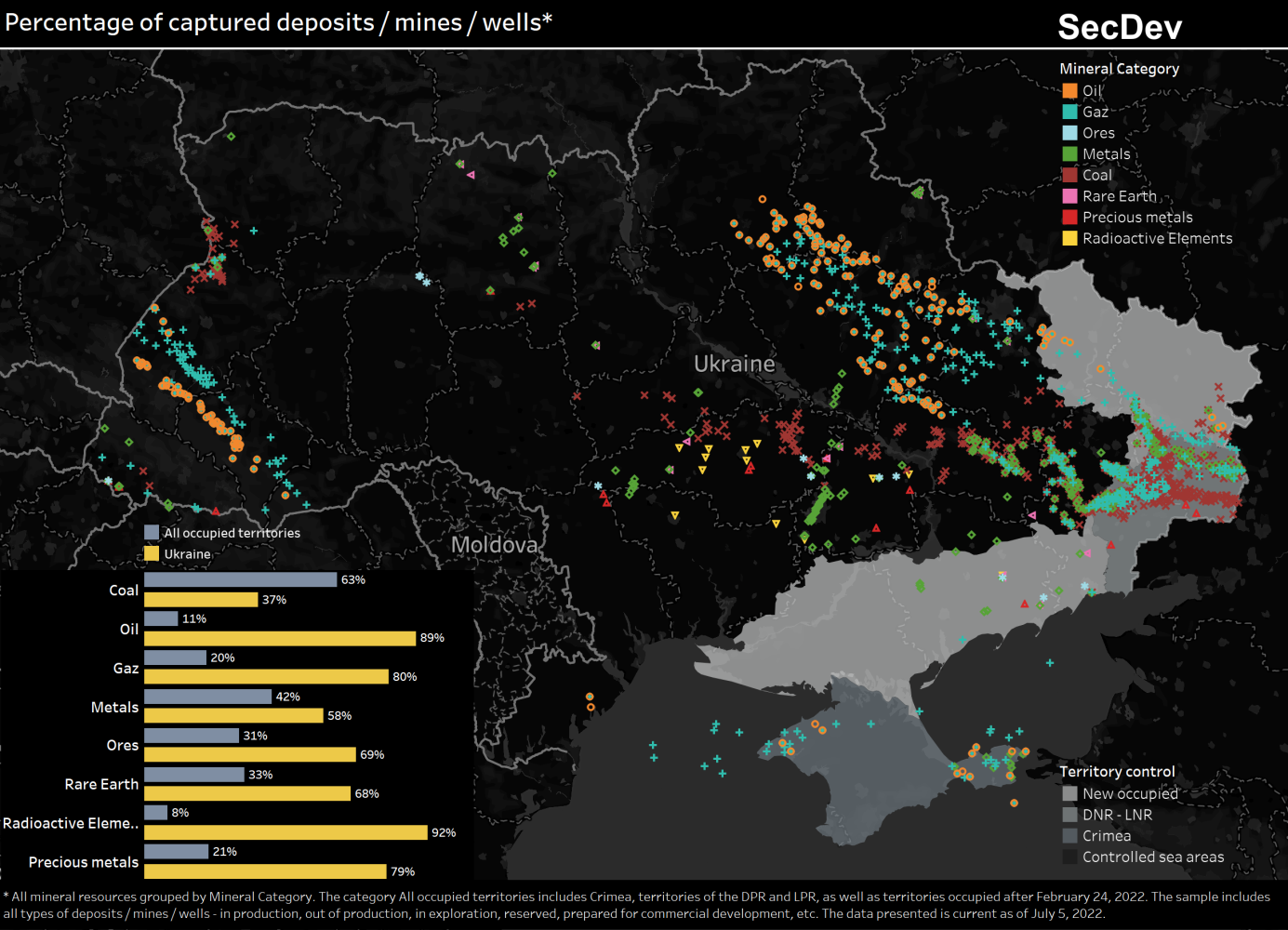

12 trillion in buried treasure

Back in autumn 2022, the Canadian think tank SecDev estimated the worth of the mineral deposits in Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine to be more than 12 trillion dollars. Of the 30 raw materials that the EU rates as being of particular strategic importance, 22 can be found in large quantities in Ukraine. These include traditional raw materials used by the energy and steel industries – such as coal, oil and iron ore – but also many that are indispensable for the energy transition such as lithium, titanium, magnesium, uranium, manganese and zirconium. Due to Ukraine’s geology, most of the largest ore reserves of, say, lithium – which is essential for electromobility and battery production – are located in the eastern and southern parts of the country. Specifically, this means in currently embattled war zones or in territories Russia lays claim to.

Soil = geopolitical influence

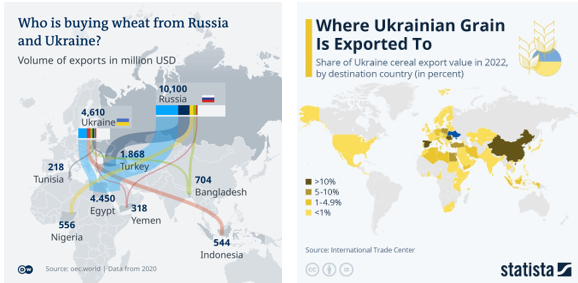

Both Ukraine and Russia already export large quantities of food products to the EU and other regions of the world. As Africa and the Middle East need to feed a growing population, they benefit greatly from food exports from the small region of eastern Ukraine and western Russia. It’s already clear that the droughts, heatwaves and shifting rain patterns resulting from climate change will make these countries, as well as Mediterranean Europe, more reliant on food imports from that region. As Ukraine still supplies food to many parts of Africa, what influence would Russia have on that continent should it gain control of these food exports? If entire world regions were to become dependent on food from Russian-controlled territory, it’s easy to imagine how Russia would use this as geopolitical capital.

My Conclusion

Given potential food shortages, a growing population, climate change, Europe’s demand for metals for industrial products, and the energy transition, I must conclude that eastern Ukraine will become even more geostrategically important in the future. In my opinion, any country looking to safeguard its own strategic and geopolitical independence should do everything in its power to ensure that these regions remain in the hands of a reliable international partner. Putin’s Russia has proven that it cannot be seen as such a partner for Europe.

After two years, many people are tired of war. I am concerned to hear a growing number of voices within Ukraine’s allies that would be willing to cede vast areas of land to Russia in order to achieve peace or at least a ceasefire. I’m convinced this would be a great loss, not only to the people of Ukraine but to all of us. After all, we must remember that we can’t simply transplant or recreate mineral deposits or fertile soil and farmland wherever we choose. We’re talking about regions that are already incredibly valuable and will become yet more valuable – and Putin knows that. In my opinion, whoever controls these regions has a crucial power-political ace up their sleeve – playable against both industrialised countries and those with weak domestic food production. Can Europe afford to give that ace to Putin?

Comments

No comments yet