A temple to science

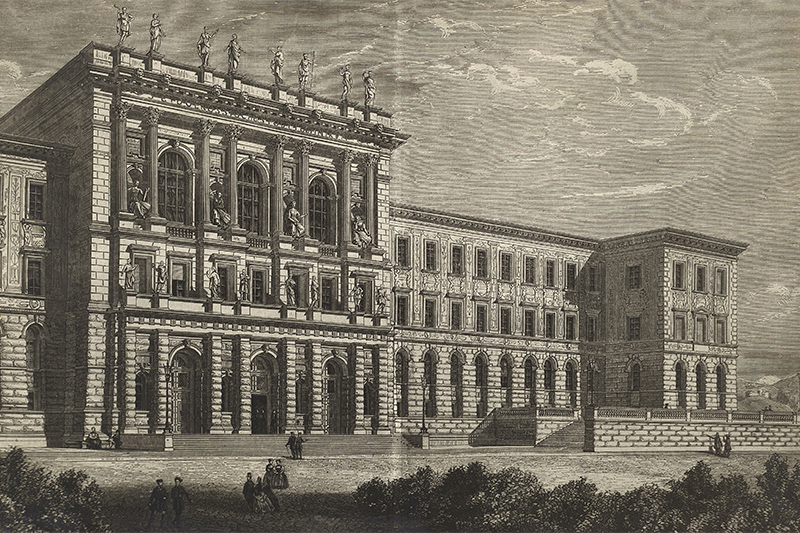

Nine years after it was founded, ETH Zurich was finally able to move into its own home in 1864. 150 years ago, this building designed by Gottfried Semper became a symbol of the ambitions of the city of Zurich and the young federal state of Switzerland. However, the road there was rocky.

“The Federal Polytechnic School is the pride of Zurich …” reads an illustrated chronicle of the city of Zurich from 1896. However, such an enthusiastic assessment could not have been easily foreseen from the outset, as the story of ETH Zurich’s main building reveals. Such a monumental structure was alien to the building style to which Zurich had previously been accustomed, for its urban planners had hitherto tended rather towards a spirit of “republican simplicity.”

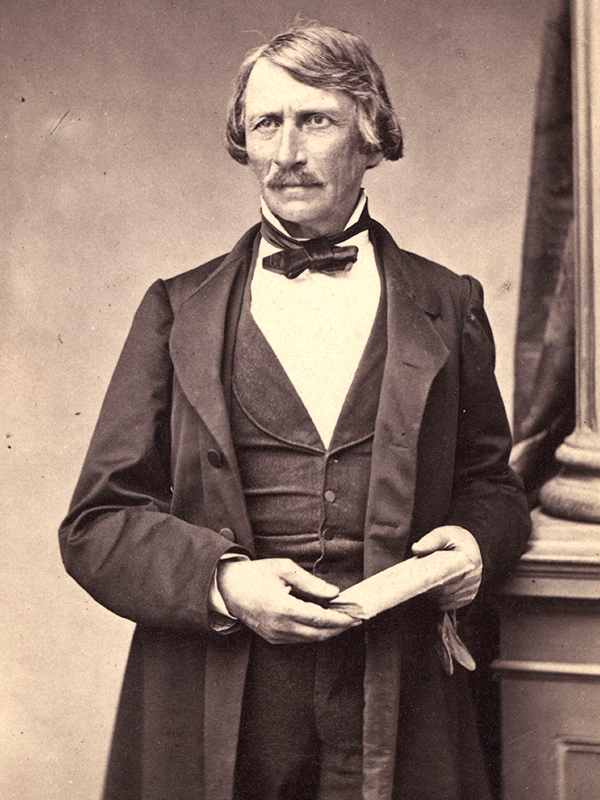

Controversial star architect

It was certainly not a foregone conclusion that the star architect Gottfried Semper, who had been teaching at ETH Zurich since 1855, would be the primary candidate to design the university’s main building. He had previously dazzled the German public with buildings such as his glitzy opera house in Dresden, the precursor to the Semperoper that is still famous today. Although Semper had also demonstrated a true republican spirit as an active participant in the Dresden May Uprising alongside Richard Wagner in 1849, his buildings and plans lacked the “republican simplicity” that was so dear to Zurich’s urban planners. When Semper moved to Zurich to take up a position at the Polytechnic School, needless to say he expected to be the architect for the new university building that was in the pipeline. And so he was suitably put out when he was instead invited to enter the competition for it that was advertised internationally.

In the end, Semper did not compete but was made a judge for it – and ultimately, none of the entrants managed to convince anyone. Or perhaps it had all just been something of a sham. Either way, the construction contract was awarded to Semper and the urban planning inspector Johann Caspar Wolff in 1858. The latter had expressly been assigned to Semper as a “guardian of the budget”, which the architect never really forgave. But in financial terms, Zurich did tend more towards frugality than largesse. The construction programme initially proposed by the University Board was deemed far too big by the Zurich cantonal government. Whereas the Board envisaged a building for 400 students, the Cantonal Council thought they would be lucky if they got even half of that. Three years later, in 1857, following some tough negotiations, a compromise was agreed: the original, more generously dimensioned construction programme would largely be adopted, albeit on condition that the University of Zurich would also be housed in the new university building. The construction costs were estimated at around one million francs. Both estimates would soon prove to be wide of the mark.

Enthusiasm and thriftiness

Semper evidently saw little reason to stick too rigorously to the specifications. He neither adhered to the original competition programme nor was he impressed with the budget he had been set. At CHF 1,740,000, it was plain to see that the confident design he submitted to the cantonal government in the autumn of 1858 would require almost twice as much funding. Nonetheless, he must have been persuasive and even managed to arouse enthusiasm for it. In the end, the main council voted in favour of the construction and the budgetary demands it entailed by a whopping 170 votes to two. It is quite possible that it was the yes vote from the entrepreneur Alfred Escher that ultimately tipped the scales – he had been the driving force behind the foundation of ETH Zurich from the very beginning. And if nothing else, the prospect that the building as planned by Semper could compete with the elegance and monumentality of the federal parliament building in Bern might have lured Zurich into showing more generosity. The Federal Council also approved the building project in February 1859.

The foundations for the main ETH Zurich building were finally dug in the autumn of 1860. After this the construction work progressed fairly quickly, even though Semper repeatedly saw himself forced into compromises for reasons of cost. For instance, the upper façade areas were fashioned out of brickwork covered in plaster, not of the sandstone ashlars he had originally envisaged. And Semper also had to kiss goodbye to the sculptures that were supposed to adorn the middle section of the west façade that towered above the city and formed the main entrance to the building at the time. However, his “temple to the sciences and arts”, as he imagined ETH Zurich’s main building, would be given a worthy interior, which is still evident today in the building’s elaborately decorated Aula.

Semper’s legacy

Much of what leaves a lasting impression on today’s visitors to ETH Zurich’s main building, however, is not actually the work of Semper, but was realised with Gustav Gull’s renovations in the early 20th century. He moved the main entrance from the west to Rämistrasse in the east and remodelled Semper’s original one-storey, central “Antikensaal” as a multi-storey main hall. And he crowned ETH Zurich with the dome still regarded as the emblem of ETH Zurich today. It was a fitting counterbalance to the tower of the new university building, into which the University of Zurich moved in 1914.

Initially, however, the University and ETH Zurich were united as planned under the roof of Semper’s ETH Zurich building, into which they were able to move gradually during 1863 and 1864. The University of Zurich was allocated the south wing. It soon became clear that the plans for the new building hadn’t been too ambitious after all. In fact, it was almost bursting at the seams from the word go, as the student numbers already surpassed all original expectations in the very first year. As it happened, the students were the least enthusiastic about the new main building because they feared (not entirely without cause) that with everything centralised in one building, they would be too much under the thumb of the University Board and its professors. Nevertheless, Semper’s building was soon regarded in neighbouring countries as a textbook example of an especially aesthetic, highly successful university building. Semper had “given Switzerland a university building that was second to none and that no other country had produced with such magnificence”, as a report in a contemporary German journal swooned.

This article was originally published in Globe 2/2014.

Comments

No comments yet