Impact of selective logging in tropical forests underestimated

Das Fällen einzelner Bäume in tropischen Wäldern wurde bisher als relativ naturverträglich angesehen. Das ist es bei weitem nicht immer, so das Fazit einer neuen Studie. Es kommt darauf an, wie stark die Wälder genutzt werden.

Tropical trees are logged because of their highly prized timber – but logging is not always done by clearing an entire forest area, where valuable habitats for flora and fauna are completely destroyed. In many tropical rainforests, trees are also logged individually, a practice known as selective logging. This involves felling selected large, valuable trees while leaving the rest of the forest more or less intact. The impact of this practice on biodiversity, however, is debatable. Previous studies that tried to summarize the impact did not distinguish between different degrees of intensity of selective logging.

Now for the first time ETH Zurich doctoral student Zuzana Burivalova and her colleagues have studied how much the impact on biodiversity depends on logging intensity. In an systematic review, she analysed data from almost 50 independent tests on the topic from the last few decades. The environmental scientist concludes that grouping so many different forest uses under the rubric selective logging provides an inaccurate picture. As ecologists have done precisely that until now, however, the researcher believes that the current view of selective logging in tropical forests is too optimistic.

Selective logging a misleading concept

“For biodiversity, it is very important how careful the loggers are during felling, as many scientists have shown before,” explains Burivalova. “What has been less considered before and what we now show in our study is the importance of the amount of timber felled in a forest. This turns out to be crucial for biodiversity.” Indeed, she says that certain forms of small-scale, low-intensity logging have only a minor impact on biodiversity if they are well organised and performed carefully. In the case of intensive logging with bulldozers and other heavy equipment, however, Burivalova explains that the collateral damage is often vast and many habitats get destroyed. In Borneo, for instance, timber concessions designated for selective logging are often logged at far too high intensities to be sustainable for biodiversity.

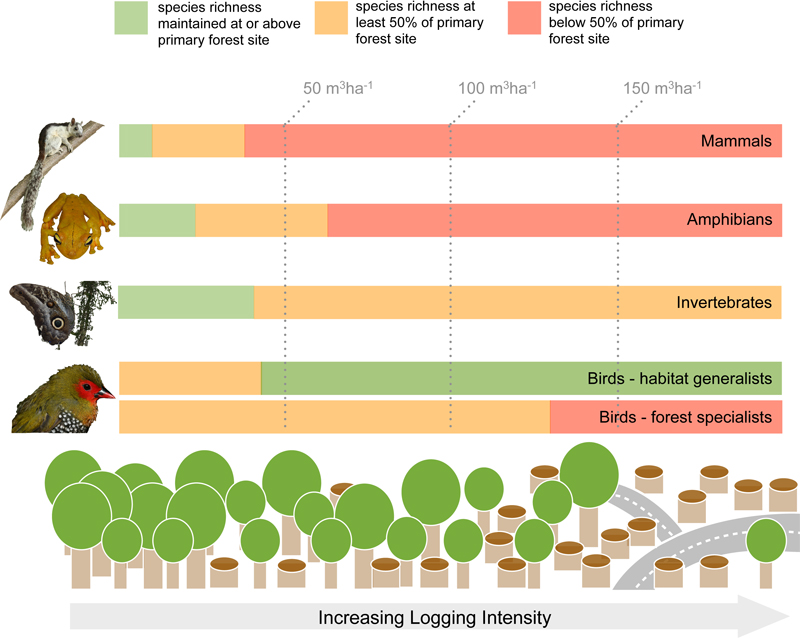

As the scientist has shown, intensive logging has a very direct negative impact on the number of mammal, amphibian and invertebrate species living in the forest. “The more heavily a forest is logged, the worse off these animal groups are,” says Burivalova.

Birds a special case

Interestingly, at first glance it seems to be a different story for birds, which appear to be less vulnerable to logging than the other animal groups studied. With increased logging, new species of bird even migrate into the forest and biodiversity climbs.

However, Burivalova puts it into perspective: a closer look reveals that the newcomers are actually species that can survive even outside of the rainforest. The bird species that are especially adapted to the tropical rainforest, however – including those that rely on a limited range of plants for food and nesting – respond to logging just as sensitively as the other animal groups studied.

In another research project, Burivalova would now like to examine why some bird species can tolerate a heavily logged forest, whereas others disappear even after light logging. According to her it might be due to the fact that bird generalists are able to benefit from the high food abundance in the temporary rainforest openings from selective logging. Forest specialists, on the other hand, might be losing their narrowly specialized habitat. With this research, the environmental scientist wants to contribute to making selective logging more wildlife-friendly in the future.

Literature reference

Burivalova Z, Şekercioğlu ÇH, Koh LP: Thresholds of Logging Intensity to Maintain Tropical Forest Biodiversity. Current Biology, 2014. 24: 1-6. doi: external page 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.065

Comments

No comments yet