How climate change may (in)directly affect us

Climate risks in distant countries affect us too: in a globalised world, if China’s breadbasket falls victim to drought, Switzerland may also feel the consequences via the supply chain. Adapting to climate change isn’t just the local issue it’s generally thought to be.

Climate change is happening, and no place is immune to the consequences. It’s true that Switzerland is unlikely to be as drastically affected as many other countries – alarming accounts of tropical storms, the flooding of entire regions or prolonged droughts generally reach us from abroad. But in today’s closely interconnected world economy where raw materials, foodstuffs and commodities are produced in distant countries and consumed around the world, extremes of climate and weather at any point along the supply chain can quickly have knock-on effects around the globe. Therefore, supply shortfalls or disrupted flows of goods could also affect Switzerland.

This year's ETH Klimarunde deals with the question of how globalised climate change affects us, and how we can deal with it.

Recognising weather and climate risks

We have no choice but to adapt to the changed – and still changing – climate. But if we want to take any proactive measures, it is imperative that we consider both the threats and the opportunities associated with climate change.

The term “risk” refers to uncertainty regarding the outcome of an undertaking, including the possibility of gains and losses that are not necessarily financial in nature. In addition, risk is not determined solely by the actual danger (extreme weather, for example) – it’s just as important to know how exposed and vulnerable the undertaking in question is. These latter two aspects are often the primary drivers of short-term risk.

Therefore, the following questions are key in the handling of weather and climate risks:

1. What weather and climate influences is my activity exposed to?

2. How will I deal with the risks? What options do I have to manage them?

3. What kind of effort and expenditure will this require? Do the benefits outweigh the costs?

If science is to make a meaningful contribution to managing weather and climate risks – in other words, if it is to help find answers to these questions – we must work in close collaboration with affected parties. This is particularly true regarding risks along supply chains: these networks do not stop at country borders, so we have to look beyond the local level when it comes to adapting to climate change.

The example of imports from China

According to the Swiss Farmers’ Union, Switzerland consumed around 880 kg of food per person in 2013. [1] The quantity of food imported was equivalent to 88 percent of domestic production. The imports were primarily vegetable products. In 2013, Swiss agriculture satisfied 58 percent of domestic nutritional requirements in terms of energy.

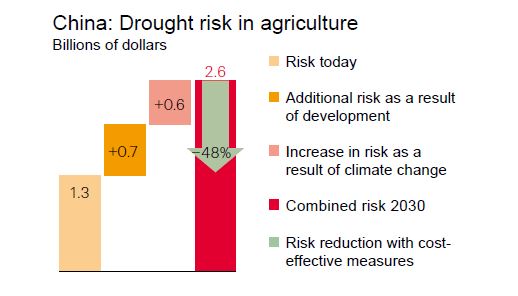

Some of these agricultural imports originated in China, for example vegetables and animal feed (imports of just over 100 million Swiss francs). [2] Drought risk in large cultivation areas in north-east China cannot be ignored. According to a detailed study carried out in close collaboration with local stakeholders, we can reckon with a long-term average crop loss of 1.3 billion US dollars under current weather conditions. [3] The projected growth of the agricultural sector raises the exposure and therefore the risk by around 700 million dollars by 2030. If we assume a scenario of severe climate change in this region, the risk increases by a further 600 million dollars. In this case, the combined weather and climate risk by 2030 would amount to around 2.6 billion dollars – a doubling of costs in less than two decades.

Minimising the threat

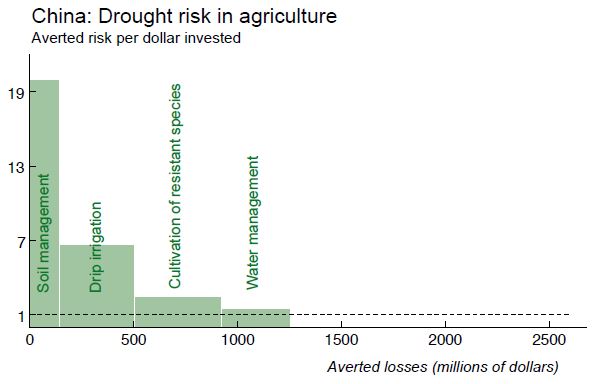

Fortunately, potential measures to reduce risk emerged from discussions with local stakeholders. In the case of the drought-threatened Chinese agricultural sector, these would include improved soil management, drip irrigation, the cultivation of drought-resistant species and a careful water management strategy. Such measures could reduce the risk by 2030 by around 48 percent. While they may not come cheap, the costs would still be far lower than the projected losses. One dollar invested in soil management could avert nearly 20 dollars’ worth of crop losses. For drip irrigation, that number is more than 6 dollars.

Raising awareness

This example demonstrates that weather and climate risks in the agricultural sector can be managed with reasonable expenditure. Currently, however, such investment is not (yet) taking place. In light of the closely interconnected flows of commodities around the world, it certainly makes sense for companies and authorities to at least consider adapting to climate change beyond their own country’s borders. This doesn't mean that we have to make the aforementioned investments in China ourselves – it is often helpful simply to make the risks better known and engage in dialogue about ways to address it.

Proactive engagement with risks also offers a competitive advantage. This fact has only been mentioned in passing here, but it will certainly be a topic of discussion at the next ETH Klimarunde on 8 November 2016.

Further information

[1] Federal Statistical Office: external page Economic accounts for agriculture: Estimate 2016 and Food and agriculture: external page pocket statistics 2016

[2] CHF 109 million in 2009. See external page Press release (Swiss Farmers’ Union)

[3] Swiss Re: Economics of Climate Adaptation – external page Shaping climate-resilient development

Comments

No comments yet