From start-up to global market leader

Sensirion and GetYourGuide: two ETH spin-offs in entirely different market sectors, but both highly successful. Their common denominators? Fruitful business ideas, entrepreneurs with the courage to venture into new territory – and the support of the right employees.

They call Rome the Eternal City – and it certainly feels like an eternity when you wait in line to visit historic sites like the Sistine Chapel. Unless you have the GetYourGuide app on your smartphone. Then you can book tickets in advance, get directions for how to get there, and visit the Vatican museums without standing in line.

An exclusive offer for travelers

“We are able to make this kind of exclusive offer because we have reached a volume that makes us an attractive partner for tour operators,” explains Johannes Reck, the 31-year-old CEO of GetYourGuide. Since the ETH spinoff set up shop in Zurich’s Technopark in 2010, it has evolved into the world’s leading agency for excursions and local tourist activities, with more than 30,000 offers in 2,000 different cities and employing 250 people at a dozen locations.

The story actually began two years earlier, with a business idea that has since been modified but is still reflected in the company’s name. In 2008, six ETH students set up an internet platform offering the services of students as tour guides throughout the world. This initiative failed because they were unable to recruit enough students to work as tour guides. But the platform nonetheless attracted the attention of tour operators who saw it as a useful advertising medium. This gave rise to the business idea for the second attempt, and the budding entrepreneurs – now a group of five – started out again.

In their efforts, the group could count on support from mentors. “The Swiss start-up culture is second to none in Europe, especially at ETH,” enthuses Reck. He continues, “I had the opportunity to meet with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and suggested that German universities should set up technology transfer facilities like ETH transfer.” It would improve the chances of young start-ups and give students the courage to try out their own ideas.

The creators of GetYourGuide certainly needed courage on more than one occasion. For instance, at one point they realised they wouldn’t be able to employ more people in Zurich, because the internet culture hadn’t yet caught on in Switzerland. They decided to set up a second office in Berlin. “In the beginning it was hard for us to manage the balancing act between the two locations,” Reck recalls, “but the experience paid off in the long term and came in useful when we started to set up offices in other countries.”

A series of new beginnings

Then came the mobile revolution that redefined the internet. Company website GetYourGuide.com was a typical desktop website that didn’t adequately support smartphones or offer apps. Virtually overnight, its owners decided to reposition the product and redirect all their resources into developing a mobile version. But technology is one thing, content quite another. The tour operators were not in the habit of offering last-minute deals, but travellers wanted to be able to book services via smartphone once they were already at their destination. And so, one challenge led to another.

It goes without saying that this all costs money – a lot of money. The company’s earnings were far too meagre, but GetYourGuide rapidly found reputable investors. Over the years, it has raised almost 100 million dollars. GetYour- Guide has never turned a profit (so far): like other internet companies, it’s all about growth. If the company manages to win out over the global competition, the financial rewards will be considerable. But it wasn’t money alone that was responsible for the start-up’s success. It’s also important to have the right investors. For GetYourGuide, they include Kees Koolen, wellknown as one of the co-founders of Booking. com. “He helped us to revise our corporate structures and define the company’s strategic orientation,” says Reck.

GetYourGuide is currently working day and night to evaluate the huge volume of existing booking data so as to be able to personalise the offers it suggests to its customers. “We are the only platform with such a large inventory of data, and yet even after seven years we are effectively starting all over again,” says Reck. Among other things, the company aims to grow further by expanding its workforce in Zurich, preferably by recruiting ETH graduates. Reck appreciates the fact that “ETH students are used to working under pressure, possess outstanding analytical skills, and have been educated to the highest standards.”

This opinion is shared by Felix Mayer and Moritz Lechner, both of whom earned doctorates in physics from ETH. They founded what is probably the best-known ETH spinoff: Sensirion employs 600 people, a quarter of whom are ETH graduates. “ETH provides an excellent education for highly talented students, both on a national and international level,” says Lechner. Mayer adds, “Obviously, we also recruit graduates from other universities, and more than half of our employees hold a university degree.”

The dream of running their own business

It has taken nearly 20 years for the two entrepreneurs to build up the company that today is one of global leaders in the market for sensors and sensor solutions. “Even as students, we knew that we wanted to set up our own company, even if that was a pretty far-fetched idea at the time,” remembers Mayer. ETH offered little in the way of support for such projects; one exception was a lecture by Branco Weiss on how to found and manage a company.

In 1998 Thomas Knecht, the managing director of McKinsey’s Swiss office at the time, joined forces with ETH Zurich to establish the “venture” startup contest. “We knew that this was our chance to realise our dream,” says Lechner. He and Mayer won the first edition of the “venture” competition, but that’s now ancient history.

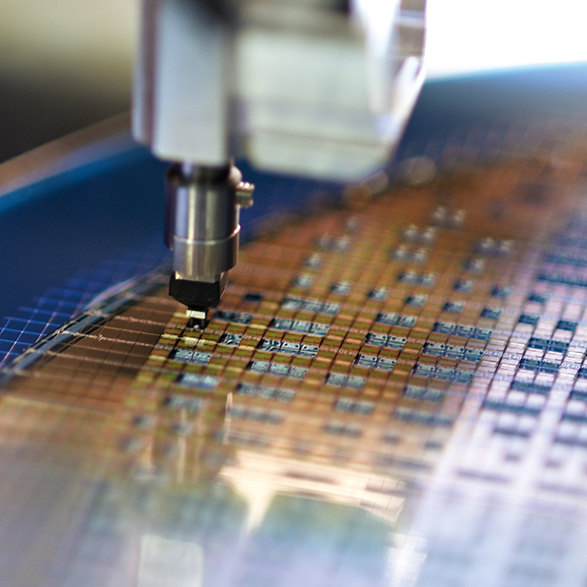

Yet despite their determination to found their own company, it took them a long time to decide exactly what product they wanted to offer. In the end, they chose to develop and commercialise two novel sensors based on Mayer’s doctoral thesis. It was a gofor- broke decision because, as Mayer explains: “ETH had made several previous attempts to transfer this sensor technology to industry. Knowing that all of them had failed definitely made us a little nervous.”

Entrepreneurial risks

To add to the challenge, developing and producing this type of technology is expensive and time-consuming. The two partners couldn’t simply set to work on their own and grow progressively from there. Right from the start, they needed an infrastructure and co-workers. They poured all the money they had into their business, even taking out loans. All this before they could start work and look for an investor – “not the usual Swiss way of doing things,” comments Lechner with a wry smile. They went on to develop two types of sensor, one for measuring humidity and temperature and the other for measuring gas flow, in the hope that at least one of them would work.

As it turned out, both products worked. They found a few customers, then more and more. The company was on course to reach break-even point, allowing the two entrepreneurs to breathe a sigh of relief. But then came 9/11, only three years after the company was founded and just as it was beginning to find its feet. In next to no time, its orders dropped by 75 percent. “It was a heavy blow that sent us back to square one,” comments Lechner.

But the company quickly recovered, continued to improve its products, and ventured into one new market after another. The first was medical devices, followed by the automotive industry and consumer goods. In the era of the Internet of Things, in which all products are equipped with smart functions, sensors have become indispensable in almost every area of industry. Would it be fair to say that the two entrepreneurs anticipated this development? “Two or three years after we founded our company, we could see that computing power was becoming cheaper, and that this would lead to an increased demand for sensor technology,” says Mayer. “We recognised this growing trend and wanted to be a part of it.” Today, Sensirion is a major player in the field.

The company’s growth has been driven by huge investment in research and development, corresponding to one fourth of its revenues, and by Sensirion’s unique corporate culture, which enables it to find solutions in even the most difficult situations. This was the case when a new gas sensor failed field tests, despite the dedicated work of 100 or so development engineers. Initial improvements didn’t solve the problem, and a comparison with rival products revealed that they, too, were unable to meet field testing requirements. “We interrogated everyone who works for the company to find out whether they saw a future for this product,” reports Lechner. The consensus was to continue believing in the sensor. They tried out a whole panoply of ideas until finally finding the one that worked – on the last attempt. As Lechner says, “That’s what innovation is all about: Stretching ourselves to the limit and leaving the safe and familiar behind. It doesn’t always work, but then you simply have to stand up and try again.”

Comments

No comments yet