A society divided by reconstruction

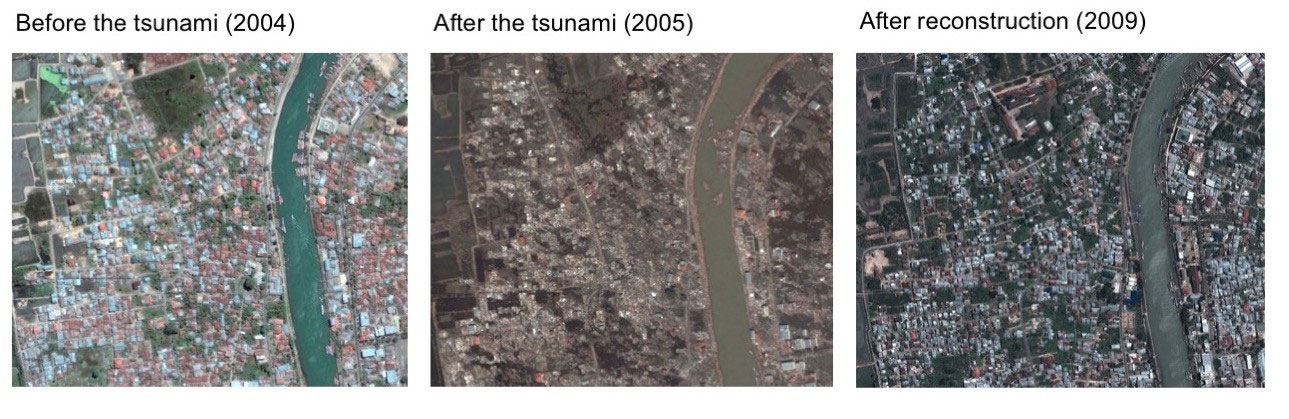

In 2004, a tsunami devastated much of the Indonesian city of Banda Aceh. An international team of researchers has studied the long-term impact that rebuilding efforts in coastal areas have had on the community.

On 26 December 2004, a massive tsunami devastated Indonesia’s coastal city of Banda Aceh, levelling nearly half of the city and killing an estimated 160,000 people across the province. Countless others lost their families, homes and everything they owned.

In the years that followed, aid providers rebuilt homes on the same plots that had been completely destroyed by the tsunami, in order to avoid displacing the residents. In doing so, they were acting in accordance with a humanitarian principle that comes into play after natural disasters, namely to help survivors to return to their previous places of residence whenever possible.

Yet in Banda Aceh, many tsunami survivors preferred to move inland instead, leading to a price premium for properties farther from the coast and socio-economic segregation. Reconstruction in the coastal zone has unintentionally exacerbated this segregation: now many lower-income newcomers rent rebuilt houses that higher-income tsunami survivors do not wish to occupy. The unfortunate result is that lower-income residents are now disproportionately exposed to coastal hazards. An international research team has now published these findings in the journal external page Nature Sustainability.

The principle of “build back better”

“The reconstruction of Banda Aceh had a goal to ‘build back better’,” says Jamie McCaughey, first author of the study and a doctoral student with ETH Professor Anthony Patt. This principle was used not only with reference to the rebuilding of houses and infrastructure, but also to people’s well-being. “While there were many successes, the reconstruction efforts did not always pan out as intended,” concluded McCaughey and the team of researchers from the Earth Observatory of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University in Singapore and Syiah Kuala University in Banda Aceh.

In 2014–2015, a decade after the disaster, the researchers studied the long-term outcomes of rebuilding efforts in the city and how residents there were affected. This involved analysing the socioeconomic characteristics of both rebuilt and unaffected residential areas and interviewing hundreds of people: tsunami survivors, newcomers, community leaders, and agency and government officials.

The unpopular coast

The researchers found that nearly all of the homes rebuilt in the tsunami-affected area were inhabited ten years later. Yet only half of the inhabitants were tsunami survivors. Over 40 percent of the people living in the new houses were newcomers: mostly lower-income renters from other regions who had not witnessed the tsunami.

According to the researchers, many tsunami survivors either never returned to live in the aid houses provided on their plots, or returned and soon left. People who could afford it settled in the more inland parts of the city, while renting out their aid house to others. “And some tsunami survivors who returned and ended up staying would like to move farther from the coast but cannot afford to do so,” says McCaughey.

This is because the rising demand for properties in tsunami-safe locations further inland had triggered a price explosion. Real estate and land prices increased sharply, making homes in tsunami-safe locations unaffordable to poorer residents wanting to move there. At the same time, the rental prices dropped for the newly built homes near the coast, drawing in poorer residents.

Poor and risky here – rich and safe there

Ultimately, this has led to a division in the urban population – with poor residents who can no longer afford to live in tsunami-safe locations on one side, and affluent residents on the other. “Before the tsunami, people did not know about tsunami risk, so there was no socioeconomic segregation of tsunami-prone areas. But now wealthier households tend to live further inland, while poorer households tend to live near the coast,” says the ETH doctoral student.

According to McCaughey, one way to avoid this undesirable segregation would be to let people choose where they receive housing aid after the disaster, regardless of their purchasing power. “Enabling people to choose where they rebuild would help those who truly wish to return to the coast to do so; at the same time, this may avoid the problems that arise from rebuilding more houses than wanted in hazard-exposed areas,” he says. Nine in ten interviewees said that they were not given this choice, however.

But it was also reported that there were many who did willingly move back to the coastal zones. “They were thankful for the aid that allowed them to resume a normal life in their familiar surroundings.” Given these diverse preferences, “we find that one size does not fit all.”

Who should choose where to rebuild?

When rebuilding in disaster areas, aid organisations and government agencies have to decide whether to relocate people to less hazardous areas or to help them resettle in the same places where they lived and worked before.

In the case of Banda Aceh, the researchers reported that a decision was made for the latter: “After the disaster, there was also a lot of pressure from donors to quickly rebuild the parts of the city that were destroyed.” Another factor was that the local authorities did not have funds for land purchases. “This limited the possibilities for relocation from the outset,” says McCaughey.

Relocation has its disadvantages, too, however: in places destroyed by the same tsunami in Sri Lanka, the authorities created buffer zones where new construction was prohibited. The former inhabitants of these areas were relocated. The new homes and people are safe from future tsunamis, but residents now have to deal with long journeys and expensive transit costs to reach their places of work.

The case of Banda Aceh, however, is not necessarily representative of all of the disaster areas rebuilt after the tsunami. “Other cases must be considered individually,” says the environmental social scientist.

“Our findings call into question the humanitarian consensus that it is generally best to rebuild on the sites where people lived before the disaster. Instead, it may be better to enable each household to choose where they resettle, as the Indonesian government had initially proposed for the reconstruction of Aceh. But to implement this, aid providers would need to overcome many difficult challenges.” This is an important policy area to examine now: “In an era of growing coastal populations and rising sea levels, decisions made after one disaster strongly influence our vulnerability to the next.”

Reference

McCaughey JW, Daly P, Mundir I, Mahdi S, Patt A. Socio-economic consequences of post-disaster reconstruction in hazard-exposed areas. Nature Sustainability 1, 38–43 (2018). doi:external page 10.1038/s41893-017-0002-z

Comments

No comments yet