Tanja Stadler explains her area of research using a tree as an illustration. During reproduction, genetic information changes – branching out like the boughs of a tree. “I answer biological questions by reconstructing the tree from genetic sequences and then calculating the biological processes from that,” she says. She skilfully explains how this approach is applicable to all areas of biology. She elaborates with particularly illustrative examples, including viruses that mutate, cancer cells that proliferate and ecosystems that evolve through time. Today, Stadler has a rather esteemed audience – patron of the sciences Max Rössler is visiting her laboratory at the ETH Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering in Basel.

Every year, Rössler endows a prize for young ETH researchers who achieve extraordinary things and would like to expand their research group even further. The Rössler Prize will be awarded for the 14th time this year. “When I look at the list of colleagues who have received this award in the past, it fills me with pride. It is an honour, and a very generous donation from someone who supports science out of their own pocket because of personal conviction,” Stadler says.

Mathematician to mathematician

This visit is special for a couple of reasons: not only is this the first time the Rössler Prize has gone to the Department of Biosystems, but it is also the first time it has gone to a mathematician. A native of St. Gallen, Max Rössler himself studied mathematics at ETH Zurich and received his doctorate in 1966 for his work on orbital calculations in space travel. After a spell as guest researcher at Harvard University, he returned to ETH, where he was a senior scientist and lecturer at the Institute of Operations Research from 1967 to 1978. Stadler therefore seizes the opportunity to show Rössler a few formulas. “It’s not every day that someone is also interested in the statistics behind our research,” she says with a grin.

Stadler is alluding here to her tenure as president of the Swiss National COVID-19 Science Task Force, which is became known during the pandemic. In this role, she was in the spotlight almost around the clock, aiming to contextualise the latest scientific findings for policymakers and the public. However, Stadler is not receiving the prize for her great commitment to the task force, but for her outstanding scientific achievements, as the ETH prize committee emphasises.

A different way to find the R value

For months, everyone was talking about one particular mathematical value: the R value, which states how many other people one person infects. As she previously did in the media, during this visit Stadler explains how she and her team arrive at the R number, but she also takes the opportunity to explain the details: “During the pandemic, we often talked about the R value which we determined based on the number of confirmed cases. Doing that requires reliable and consistent testing. In our research, we primarily calculate the R value based on a virus’s genetic information. The advantage here is that we can determine the R value at the beginning of an outbreak, before we have complete data. That helps us assess how transmissible a new pathogen might be.” Incidentally, the ETH researcher began working on this type of problem before the pandemic – as early as 2014 Stadler was researching how Ebola spreads.

Stadler wrote her dissertation on “evolving trees” at the Technical University of Munich before joining ETH Professor Sebastian Bonhoeffer’s Theoretical Biology group as a postdoc in 2008. During this time, she discovered an interest in infectious diseases. In 2014, she became assistant professor in the Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering in Basel. Stadler is now a Full Professor of Computational Evolution and has 15 members in her group.

Collecting large amounts of data themselves

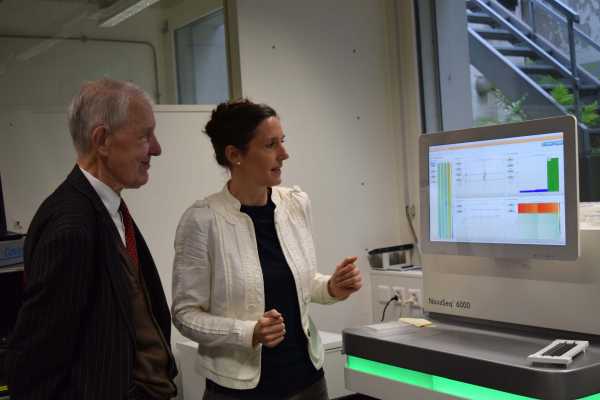

Without appropriate data, research can’t move forward. And so, together with Rössler, Stadler also visits the department’s sequencing laboratory where her research group generated an incredible amount of its own data – during the coronavirus pandemic but also prior to it. Rössler is extremely fascinated by this technical aspect as well: What genetic data can these machines produce? How efficient are they? How does the data get from the machine into the statistical tool? And what does such a device cost, anyway?

It is precisely this mix of biology, the ability to sequence genomes, and the statistical methods Stadler is developing that makes her research so exciting. “We have plenty of ways to collect genetic data; the challenge is to extract useful information from it. This is exactly why we need mathematics. It allows us to eliminate the noise in the data, classify the data with less ambiguity and contextualise it better. Ultimately, we can use the data to make more relevant statements about epidemics,” Stadler says.

The virus report of the future

The experience that their research offered a great benefit to society has had a lasting impact on Stadler and her entire group. This is also reflected in how they plan to use the funds from the Rössler Prize. At an in-depth retreat, the group will jointly analyse exactly what is most urgently needed from statistics in the event of a renewed pandemic threat. The prize money will then be used to close the identified knowledge gap.

And where would Stadler herself like to be in ten years? “I’m committed to ensuring that we collect core data globally, connect with each other better, evaluate the data together, and make the data and analysis results easily accessible to people,” she says. “I think of it as a kind of ‘infection report’ similar to the weather report, where people can see, ‘Oh, the flu is going around a bit more in Basel right now – ok, I’d better be careful and take precautions’.”

Comments

No comments yet