A human model for autism

The CRISPR-Cas gene scissors enable researchers to study the genetic and cellular causes of autism in the lab – directly on human tissue.

In brief

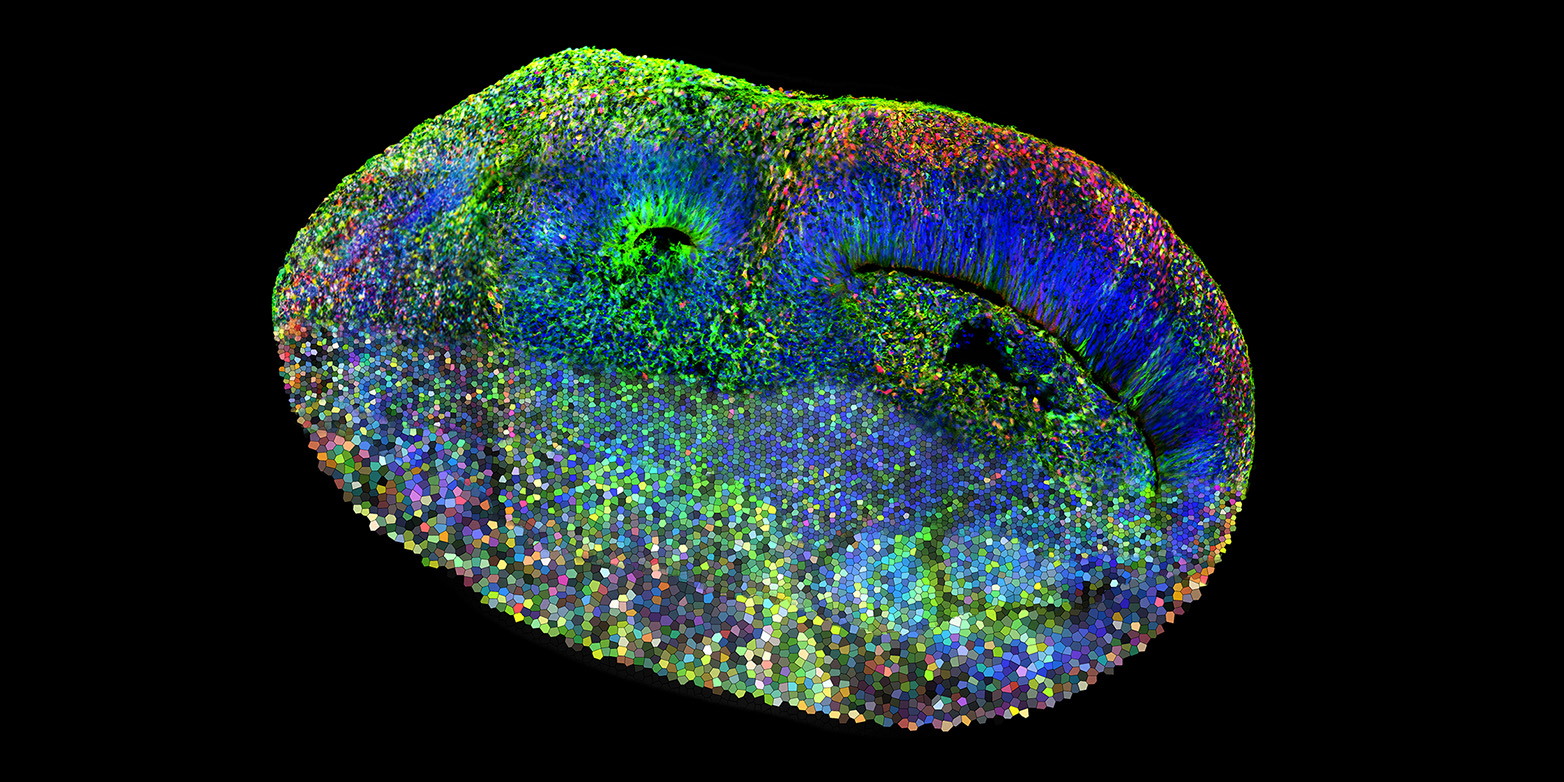

- Researchers have developed a method via which they can alter cells in miniscule human tissue cultures known as organoids in a mosaic-like manner.

- The technology helps to speed up the search for the molecular causes of hereditary diseases and peculiarities of brain development such as autism.

- Research with organoids is an alternative to animal testing and helps to reduce it.

How does autism develop? Which genes and cells in the human brain contribute to it? A new brain organoid model allows researchers from the Department of Biosystems at ETH Zurich in Basel and colleagues from Vienna to investigate these questions in human cells. Organoids are microtissue spheroids that are grown from stem cells and have a similar structure to real organs – in other words, they are miniature organs of sorts.

With them, and with a new method for modifying genes within these organoids using the CRISPR-Cas gene scissors, the researchers found out which genetic networks in which cell types in the brain are responsible for the development of autism. “Our model offers unparalleled insight into one of the most complex disorders affecting the human brain and brings some much needed hope to clinical autism research,” says Jürgen Knoblich, Professor and Scientific Director of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna and co-author of the study.

Changing different cells in different ways

This new method enabled the researchers to genetically modify the cells of a brain organoid in a mosaic-like fashion and then study them systematically. Specifically, the scientists altered one of 36 different genes associated with autism in each of the individual cells and studied the resulting effects. “We can see the consequences of every mutation in a single experiment, thus reducing the analysis time drastically when compared to conventional methods,” Knoblich says.

The new method was developed by researchers at the IMBA in Vienna, based on previous methods. In the current study, the group led by Barbara Treutlein, Professor of Quantitative Developmental Biology at ETH Zurich, incorporated the computer-assisted analysis of the raw research data: changing multiple genes in parallel in a human organoid and analysing the resulting effects at the level of thousands of individual cells creates a vast amount of data. To manage it all, Treutlein and her team used state-of-the-art bioinformatics methods.

The advantage of human tissue

In human disease research, organoids offer advantages over research using lab animals: unlike in lab animals, human genes and cells can be studied in organoids. These advantages are particularly significant in neuroscience, as the specific processes responsible for the development of the human cerebral cortex are unique to the human brain. Neurodevelopmental disorders in humans are due in part to these human-specific processes in brain development. For example, many human genes that confer an increased risk for an autism spectrum disorder are genes that are critical for cortex development.

Previous studies have shown a causal link between certain gene mutations and autism. However, scientists still don’t understand how these mutations lead to defects in brain development and the expression of autism spectrum disorders. Due to the uniqueness of human brain development, the utility of animal models in this case is limited. “Only a human model of the brain like the one we used can reproduce the complexity and particularities of the human brain,” Knoblich says.

Early brain changes lead to autism

In their organoid model, the researchers were able to show that the genetic changes that are typical for autism affected mainly certain types of neural precursor cells. These are the founder cells from which neurons are created. “This suggests that molecular changes occur at an early stage in fetal brain development that ultimately lead to autism,” says Chong Li, a postdoc at IMBA and one of the study’s two lead authors. “Some cell types we identified are more vulnerable in autism and should receive more attention in future research.”

In addition, the scientists revealed that there are connections between the 36 genes they studied that confer a high risk for autism: “Using a program we developed, we were able to show that these genes are connected to each other through a gene regulation network, and that they interact with each other and have similar effects in the cells,” says Jonas Fleck, a doctoral student in Professor Treutlein’s group and likewise a lead author of the study.

Reducing animal testing

To test whether the results from the organoid model can actually be applied to autism sufferers, the researchers teamed up with clinicians at the Medical University of Vienna to produce brain organoids from two stem cell samples from affected individuals. They found that the organoid data closely matched clinical observations in the affected individuals.

The researchers emphasise that their technology for changing organoid cells in a mosaic-like fashion can also be used for organoids of other human organs and to study other diseases. This is a new research tool for rapidly examining a large number of disease-associated genes. “This technology thus helps to obtain relevant research results directly with human organoids in cell culture,” Treutlein says. “What’s more, human organoid disease models can also be used to test drug efficacy, which can help reduce animal testing.”

This article is a revised version of a external page press release from the IMBA.

Reference

Li C, Fleck JS, Martins-Costa C, Burkard TR, Themann J, Stuempflen M, Peer AM, Vertesy Á, Lttleboy JB, Esk C, Elling U, Kasprian G, Corsini NS, Treutlein B, Knoblich JA: Single-cell brain organoid screening identifies developmental defects in autism. Nature, 13 September 2023, doi: external page 10.1038/s41586-023-06473-y

Comments

No comments yet