“The way that our cities, houses and flats are built right now makes us feel dependent.”

For many people, architectural norms create barriers to accessibility. How might we re-imagine our built environment to make it more inclusive?

Architecture can be brutal, says Spanish architect Anna Puigjaner. “It constantly divides society into those who can – and those who can’t,” she explains. “Take a staircase, for example: it’s just one architectural element, but it draws a sharp line between people who can climb stairs and people who can’t.”

Many architectural norms are actually only suited to a minority, and for some people, they may even create insurmountable barriers. “Architecture isn’t neutral; it has a real impact on society,” says Puigjaner. “Unfortunately, architecture has reinforced and reproduced a whole host of prejudices over the past few decades.”

Architectural norms for a minority

For example, most homes are still designed with the needs of a nuclear family in mind: a living room where everyone can meet, one or two small bedrooms for children, and a larger bedroom for the parents. This reinforces the prejudice that most people live in a nuclear household. “Yet in Switzerland, and in my home country of Spain, only around a quarter of people live in such traditional structures,” says Puigjaner. “So, what about the other three-quarters who don’t live like this?” Households come in many different forms. They include people who live alone, friends who live together, childless couples, large families, patchwork families, queer families and single parents. Yet for decades, the space they inhabit has been tied to a fixed standard. “That breeds a lot of preconceptions and entrenches existing power structures, including within families. The very fact that we give parents more space makes them seem more important than their children,” says Puigjaner.

Architecture that divides

Puigjaner advocates a form of architecture that does not create division. She was appointed as Professor of Architecture and Care at ETH Zurich in early 2023, and one of her focuses is the ageing society and the associated rise in health problems and disabilities. “We’re in a global care crisis, and we need to find new ways of dealing with it,” she says. “Architecture is a big part of the problems we face in this area.”

Specifically, her professorship examines the impact that things like care provision have on individuals and society as a whole. It looks at how the need to go shopping and run everyday errands affects people, and it asks what architecture can do to break down barriers in this context. “The private sphere is still the place where things like personal hygiene, taking medication, and more mundane activities such as cooking, cleaning and washing take place – and our houses, villages and cities are designed to reflect that,” says Puigjaner.

As a result, care work – which encompasses caregiving and support for household members as well as domestic chores – is still stuck in the nuclear family mindset, which expects members of households to live together under one roof and look after one another. This premise, which seldom corresponds to the reality of older people’s lives, has far-reaching implications. “In our ageing society, many people are unable to look after themselves and perform daily chores and caregiving tasks in the way they were once expected to do,” says Puigjaner. “We’ve created a built environment that encourages all sorts of asymmetrical dependencies, and it’s time we redefined how that works.”

Everyday hurdles

“These obsolete structures put enormous pressure on the healthcare system and on us as citizens,” Puigjaner adds. “They draw a sharp distinction between different segments of society, between dependent and independent individuals – in other words, between those who can, and those who can’t.”

Many older people have to leave their home to access certain types of care, support and amenities. This can force them to travel significant distances. For many, even cooking can be a struggle, because they are physically or mentally incapable, explains Puigjaner. “We therefore need to design our villages and towns in a way that eliminates the binary between dependents and caregivers and replaces it with productive interdependencies,” she adds.

And it’s not just the elderly or people with physical disabilities who count as dependent: all of us are likely to experience different kinds of dependencies during our lifetimes, whether as children, as parents, when we have a health issue, or while living alone.

Accessible learning

ETH Zurich also aims one day to be fully accessible to everyone. Most of its teaching and research buildings already meet the legal requirements. But fostering inclusiveness and participation is about more than just eliminating obstacles to mobility and navigation on the university grounds and in its buildings; it also means offering education in an accessible format. That’s why ETH launched its Digital Accessibility project, which is part of the Barrier-free at ETH Zurich programme. By harnessing digital materials, this e-accessibility project aims to promote accessible learning at ETH.

Moving care into the public realm

Care work needs to be redefined and shifted from the private to the public sphere, says Puigjaner: “We need to consider the daily tasks and chores that involve dependence as part of urban planning, as part of the public infrastructure, just like we do with libraries or with the water and electricity supply.” By taking care work out of the “hidden” private realm, she says, we can fulfil many of society’s needs and break down barriers for an ever-expanding segment of the population.

Puigjaner argues that we should promote infrastructure that makes it easier for people to care for themselves and run everyday errands; for example, by making such infrastructure easy to access and by combining as much as possible under one roof. She believes such an approach would also ease the economic burden on the healthcare system and relieve pressure on care institutions such as community health services.

Puigjaner has been looking at how shared kitchens and day-care centres can bring people together. She is particularly interested in Japan, which – just like Switzerland – has an increasing proportion of elderly and single-person households. Since the devastating earthquake in Fukushima in 2011, there has been a rise in the number of people who report feeling helpless and excluded. Efforts to address their needs include the creation of a new type of shared kitchen in Tokyo, which operates like a community centre and is open to everyone. “These urban kitchens are a meeting point for neighbours, where people can come together to cook and eat. They don’t replace people’s private kitchens – they complement them,” she says.

In Singapore, the government began setting up shared kitchens a few years ago. The result was a substantial drop in spending on elderly care. “The people who use these kitchens provide mutual support, which greatly reduces dependency,” says Puigjaner. “It’s a naturally evolving form of healthcare, and we need to look at how to make that part of urban planning.”

About

external page Anna Puigjaner is Professor of Architecture and Care in the Department of Architecture. Generous funding from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) helped set up the professorship.

Momoyo Kaijima is Professor of Architectural Behaviorology in the Department of Architecture at ETH Zurich.

Making it routine

Bogotá took this one step further with its “Manzanas del Cuidado” programme, in which authorities in Colombia’s capital converted little-used libraries into public day-care centres. These include a laundry service, a public nursery and a kitchen that anyone can use, as well as spaces where medication can be obtained and taken.

The Manzanas del Cuidado have been hugely successful and could be a good example for Europe to follow, says Puigjaner. “The way that our cities, houses and flats are built right now makes us feel dependent,” she explains. “If we can’t handle something within our own four walls, we’re told that we have to go to a dedicated place to get help. Imagine how it would transform society if, instead, we could make all that part of our daily routine! If we could choose whether to cook at home or in a shared kitchen, even when we were still capable of cooking by ourselves. Then, when the day came where we needed support, we wouldn’t feel we were dependent on anybody or anything. We would simply follow the same routine and continue to have those same relationships with other people.”

Rethinking education

Momoyo Kaijima also emphasises the connections between society and architecture. “The architecture industry as we know it has existed for around 150 years. For a long time, the established structures and construction processes were fit for purpose. But nowadays we’re increasingly aware of the ways in which architecture can exclude people and the impact this has on individuals and on society as a whole,” says ETH professor Kaijima, who originally hails from Japan.

Like Puigjaner, Kaijima is keen to question norms and overcome barriers. In her case, this means focusing on public buildings in areas such as administration and education. Classrooms have barely changed for decades, she says, and teachers still stand at the front of the class, even though that no longer makes much sense. “Teachers and pupils are both meant to be working towards a specific learning goal together. They don’t need a rigid structure to achieve that. Instead of facing each other, they could be exchanging ideas and discussing things in small groups – and breaking down the invisible barrier between them in the process,” Kaijima explains. In her view, the educational content that modern schools wish to provide should also shape the architecture – including the design of the classroom and the school building itself. And she firmly believes that a place of learning should be geared not only towards the children and the teaching staff. The population in both Switzerland and Japan is ageing, while the number of children is declining, especially in rural areas. “That’s going to cause problems in the future, but at the same time it’s a wonderful opportunity to think about how we define quality in learning, to reflect on what we can learn from each other as a society, and to imagine how a building can be accessible and suitable for different generations, from small children to the elderly,” she explains.

Kaijima’s goal is to forge connections not only between the generations, but also between people from all sorts of different backgrounds and lifestyles. Together with her students at ETH, she is studying the interactions between these different realms in the hope of finding new ways to overcome barriers, inhibitions and anxieties.

Everyone is included

Switzerland’s current building rules and regulations primarily address issues of physical accessibility, such as the maximum distance a wheelchair user should be expected to negotiate. Both ETH professors criticise the lack of similar provisions for neurodiverse individuals. “The incidence of mental illness and disorders in our society is increasing, and architecture should be responding to that,” says Puigjaner. “For example, we need spaces that are less visually stimulating and easier for people to negotiate, as well as different kinds of entrances and exits and also niches that people can retreat to.”

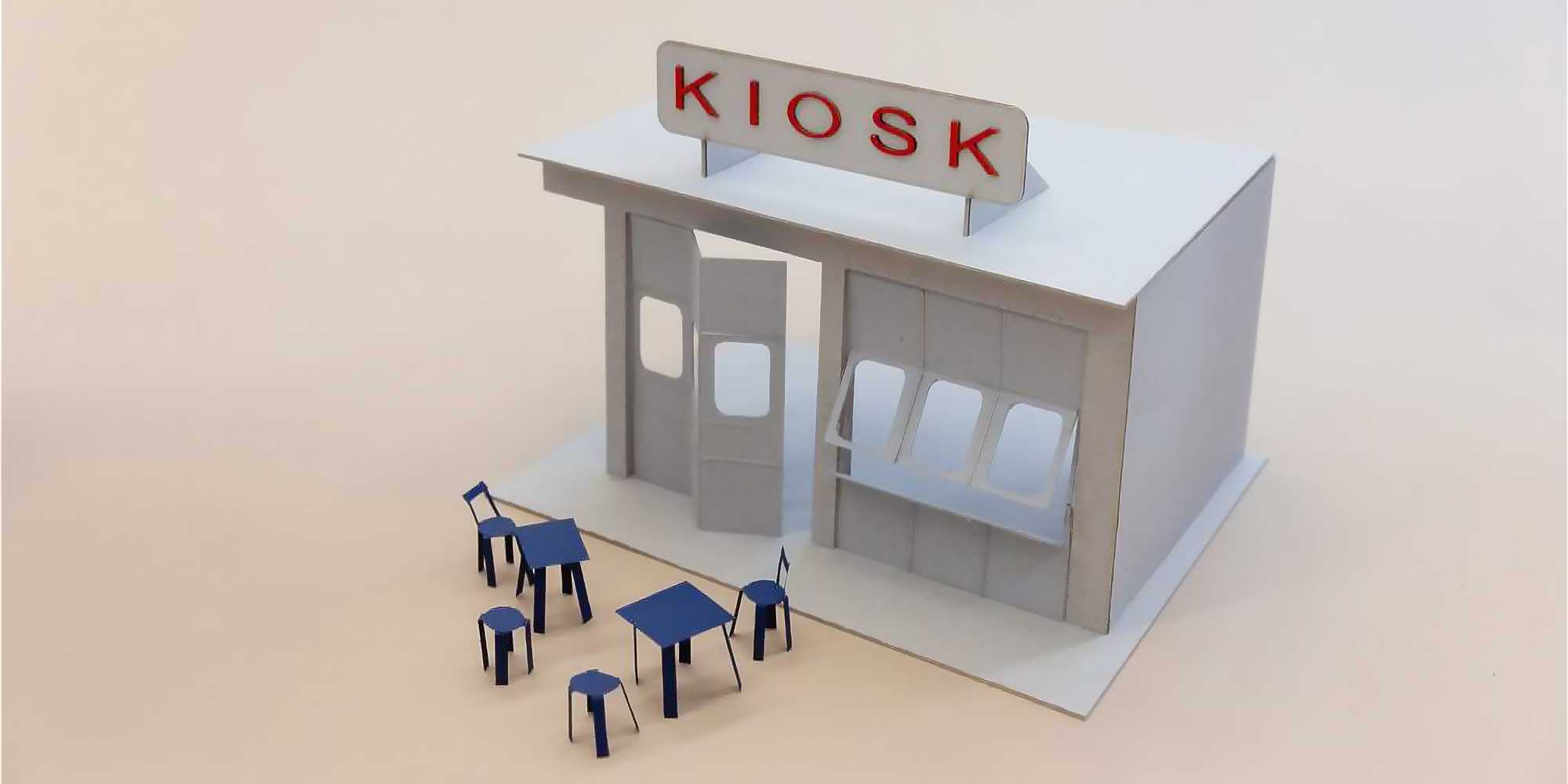

In the Spring Semester, the Architecture and Care professorship ran a course in conjunction with Theater HORA, which employs actors with learning disabilities. Together, they developed a model of an inclusive city that would reflect the needs of as many people as possible, regardless of disability or neurodiversity. “The collaboration was very fruitful, and it prompted the students to reflect on urban spaces and inclusion and consider what needs to change in architecture,” says Puigjaner.

No time to lose

Today’s students are very open to the concept of inclusion and acknowledge the need for a shift in mindset, say the two architects. That’s important, because both professors agree that the next 20 years will see architecture undergo a major transformation.

“Obviously we can’t simply demolish everything and build again from scratch. But we do need to find out how we can renovate our existing structures and make them physically accessible to as many people as possible,” says Kaijima. Puigjaner agrees: “We need to think fast, because demographic change is happening at an alarming pace, and architecture is slow to shift. But at least we can make sure we’re ahead of the curve!”

Comments

No comments yet