Lord of the flies, king of data and proud owner of seven bicycles

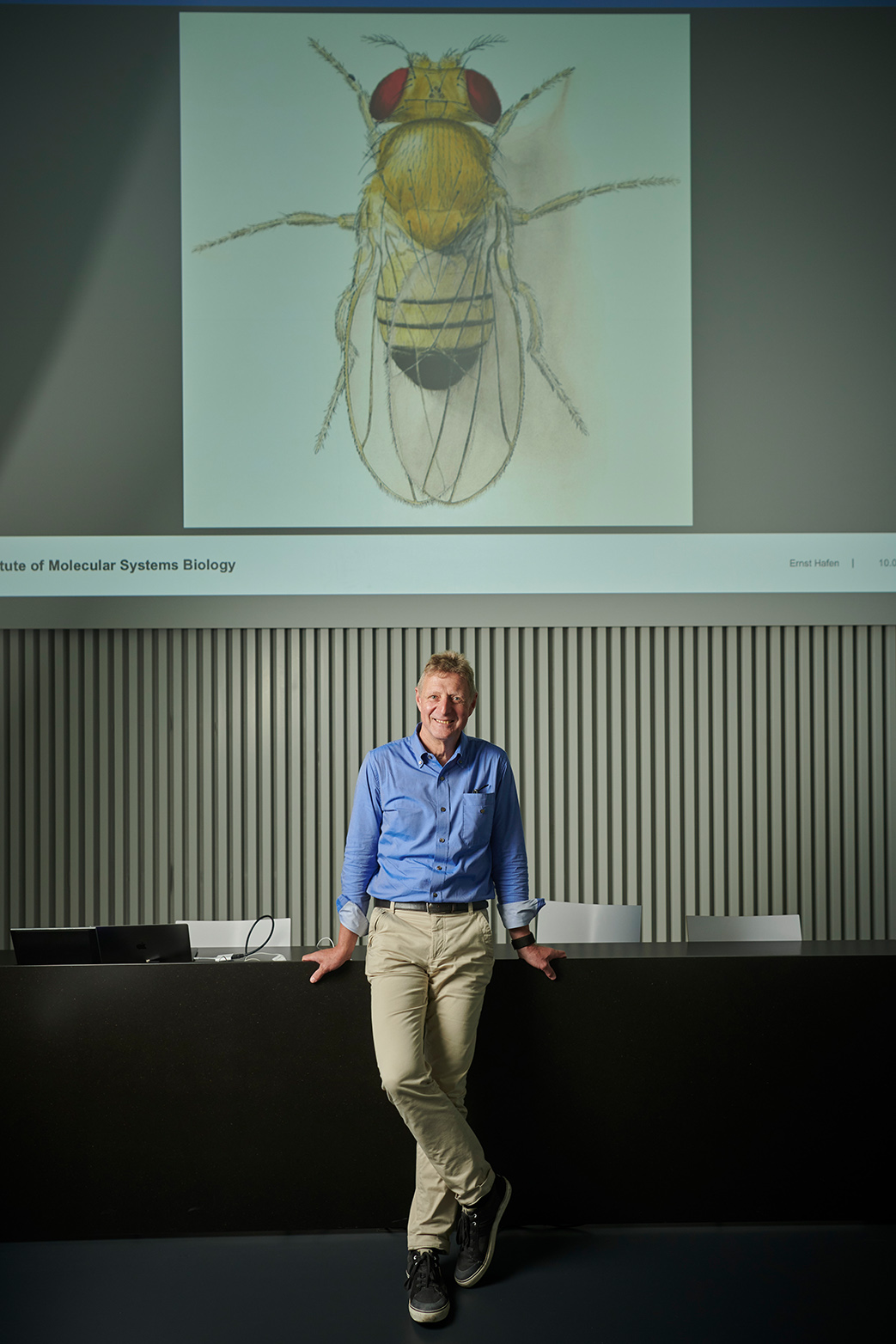

ETH professor and molecular biologist Ernst Hafen retires at the end of July. We look back at the colourful career of a leading scientist with many different interests beyond the narrow world of molecular genetics.

The end is in sight. The end of his ETH professorship, research projects and teaching. Ernst Hafen has come to terms with the realisation that he is reaching the end of his time as an active professor. “There are no more loose ends,” he says, seated at the table in his office.

He has disbanded his research group. Only one member remains, left to continue Hafen’s final research project into the health of honey bees. For the past five years, Hafen and his wife have kept bees on the roof of their garage in Zurich. They have faced all the problems that commonly affect bees, especially the parasitic Varroa mite that devastates bee colonies. This was the inspiration and motivation that led to the launch of his research project into bee health.

This does not mean he is working outside his usual field of research. The aim of the project it to test new approaches to improve bee health with the help of the fruit fly, Drosophila, which Hafen has used as a biological model in much of his research activity over the past 45 years.

Hafen’s scientific career began with a PhD in developmental biology in 1983 from the Biocenter at the University of Basel. During his doctoral studies he managed to prove how and where genes that determine the number of body segments in fruit flies are activated in the embryo. He then went on to study the genes that control the fate of cells. This led him to discover key mechanisms that play an important role in the growth of cancer cells. “The change in the cell fate is part of carcinogenesis. What’s interesting here is that the same genes are involved in both fruit flies and humans. This is because humans and flies had the same ancestor 600 million years ago,” he explains.

This triggered an explosion of research into flies at the time, because it was possible to identify the genes for developmental processes much quicker for Drosophila than for humans, and these genes are also relevant for human diseases. Ernst Hafen has received many prestigious awards for his research, including the Ernst Jung, Friedrich Miescher and Otto Naegeli Prize.

Trying to outshine his father

Hafen’s interest in biology was sparked by his biology teacher in Gymnasium. “I never took part in the ‘Swiss Youth in Science’ programme,” he says, with a grin. “But I had a really good teacher at Gymnasium who inspired me in the subject.” There may have been another factor driving his ambition: his father – a talented German scholar, teacher and rector at the Gymnasium in Münchenstein – was actually comparatively poor at biology, and the son saw this as an opportunity to outshine this patriarchal figure. So he signed up to study molecular and cell biology at the Biocenter at the University of Basel.

Ernst Hafen first came across flies while attending the lectures of the late Walter Gehring, a well-known Swiss developmental biologist. Gehring had described how the nuclei divide in yolk-rich Drosophila eggs until there are thousands of them. Some of them then migrate to the posterior pole of the egg, where they transform into future sperm and egg cells. Even back then, Gehring predicted there must be unknown RNA molecules that are taken up by these cells and control their development. Hafen wanted to solve the problem, and so he applied to work with Gehring, who turned him down initially as there were no vacancies in his research group. Hafen tried again three times – until he eventually managed to join Gehring’s laboratory to work on his dissertation.

“Ultimately I never actually discovered which molecules were responsible for controlling the fate of these cells. But I developed a method for localising these determinants and visualising them on the fly embryo. After three years of failure, that was my scientific breakthrough,” he recalls. He has the proof, in a frame in his office: the cover page of the acclaimed journal “Cell” from 1984.

This discovery also gave his doctoral studies a new direction: genetics as a method for understanding developmental biology. “I was fortunate to work with two American postdocs, Mike Levine and Bill McGinnis.” This was a formative period for Hafen: he immersed himself in the lifestyle and ethos of Levine and McGinnis. “Those two showed me a whole new world. They had a different work culture. Life in the laboratory was more exciting than life at home. Sometimes we sat in the lab at three in the morning, smoking and drinking beer together.” After finishing his dissertation, Hafen moved to America to take up a postdoc position in Berkeley in 1984. It was during this period that he discovered a gene in flies that was known to be a cancer gene in humans.

After three years in the US, Hafen and his wife, along with their first two sons, returned to Switzerland, where their third son was born. He had applied for the post of assistant professor at the University of Zurich Institute of Zoology. Following his initial appointment in 1987, he was made full professor in 1997.

One year as ETH President

But Ernst Hafen was not just the “fly doctor”, as his son Timothy once called him when asked by his teacher about his father’s profession. “I always had a lot of different interests, including university politics,” he remarks. When ETH Zurich was looking for someone to succeed Olaf Kübler, due to step down as ETH President at the end of 2004, Hafen’s application was successful. He took up office on 1 January 2005, at the same time giving up his job as professor at the University of Zurich.

The ETH Board asked Hafen to reform the university along the lines of the Anglo-Saxon model. However, this ambitious reform project met with stiff opposition from the ETH professorship especially, and eventually came to nothing. This prompted Hafen to step down prematurely after just one year in office.

Back to studying flies

He stayed at ETH and was appointed professor at the Institute of Molecular Systems Biology, headed by Ruedi Aebersold, his friend and colleague since student times at the Biocenter in Basel. Their paths had separated while they were still studying: Aebersold started working with proteins, and Hafen with genes. However, Hafen was instrumental in persuading the pioneer of proteomics to return to Switzerland in 2004 and then take charge of the newly founded Institute of Molecular Systems Biology in 2005.

His appointment also benefited Hafen, by helping him find his way back to fly research. Hafen initiated “WingX”, a subproject of “SystemsX.ch”, the Swiss systems biology initiative launched by Aebersold. Its goal was to discover how an entire genome interacts in order to determine the size of the fly wing in a natural population of Drosophila. “With this project, we were able for the first time to study not only the effect of individual genes, but the interaction of the entire genome, all gene transcripts and the proteins based on them,” Hafen recalls. This had never been possible in such detail before. “It was only possible because I worked at the institute and was able to collaborate with Ruedi Aebersold. It was an excellent arrangement for basic research into flies.”

Data – a new hobby horse

After stepping down as ETH President, Hafen focused increasingly on questions and problems that had nothing to do with his research on flies: the treatment of personal (health) data.

More and more data about genomes, health and disease are now emerging not only from research and healthcare, but also from private individuals – the advent of smartphones and smartwatches continuously measuring body functions and movement. ”Each of us has the right and opportunity to collate far more personal health data than Google would ever be able to and make it available to our doctor or for research,” Hafen stresses.

He has noticed, however, that people leave the gathering together of their personal data to the tech giants, and he is campaigning against this:

“We have the right to bring together our personal health data in an appropriate way, rather than leaving it to Google or Facebook, who simply want to monetise the data.”Ernst Hafen

Hafen is therefore advocating the construction of a parallel data ecosystem under the control of each individual. As a solution, he proposes data cooperatives acting as trustees. Their job is to gather the private health data, prepare them, make them interoperable and present them in anonymised format in a digital data commons. This data commons also controls whether (and how) companies can access and use the data for commercial benefit – as long as they pay for the privilege. But the data stay in the commons. “Citizens themselves can then actively choose whether they want to make their data available for commercial or social purposes,” Hafen explains.

This prompted him to set up the association Data and Health to promote data cooperatives, which in turn led to the founding of an actual data cooperative, “Midata”. Having fulfilled its mission, the association has now been dissolved, but Midata still exists – although “it’s only as successful as limited funding allows,” says the ETH professor. He concludes that many CEOs and policymakers he spoke to thought it was a good idea, but they struggled to imagine how it should actually be implemented. So no one was prepared to put up the necessary funding. Even so, Hafen is still convinced: “A data cooperatives are a fair and democratic solution”.

Refining a successful teaching approach

Apart from research into flies and health data, Hafen has always been interested in teaching. “You mostly work on your own in teaching, unlike research,” he comments. There are also far fewer role models – at the most, some favourite professors from one’s own time as a student whose teaching style is worth copying. He wanted to change that – which was part of the reason for the launch of the “clicker” system. This allows students to respond directly to teachers’ questions during the lecture. The teacher can then immediately check how many correct answers are received. The clicker system makes large, anonymous lectures far more interactive.

The roll-out of this device was the first step towards more interactive teaching and ultimately led to the founding of the “Center for Active Learning”. This in turn encouraged numerous initiatives to improve teaching in the Department of Biology. The bigger lectures in basic biology are now supplemented by group work, personal study and learning journals. “This was only possible because we had built up a team of professionals comprising of postdoc biologists working in the Center who were able to discuss issues on an equal footing with biology lecturers. The fact that I managed to build up this Center in D-BIOL over the past 15 years, and that it has continued to flourish, is what gives me the greatest pleasure today,” Hafen concludes. What’s more, he can easily imagine continuing to work on this project after his retirement.

Breaking away and leaping into the saddle

At the moment, however, the 65-year-old is about to embark on a project that has nothing to do with science. Apart from flies and data, he has been passionate about cycling since childhood, and is the proud owner of six bicycles and a tandem. He is already turning his thoughts towards a big adventure planned post retirement on 31 July: a mountain bike tour on the Great Divide Trail, which stretches 4,400 kilometres across the Canadian and American Rocky Mountains. It will take him and his friend three months to complete. The pair have already tested their equipment on warm-up tours around Switzerland.

But is he fit enough for such a long tour? He’s a little out of form at the moment: forced to work from home due to Covid, he has not been cycling the 30 kilometres or so when commuting to work every day from his home in Hönggerberg. Now he needs to invest some time in training, which is not difficult for such an athletic retired professor. “Over the course of such a long tour, we are bound to get fitter from day to day. We just need to take things a little easy to start with.” He’s already had experience of lengthy cycle tours – three years ago he crossed America on a tandem with his wife.

Comments

No comments yet